“Lowell’s ‘other’ famous football playing author” by Jay Gaffney

Longtime Tewksbury resident Jay Gaffney (who recently moved to Lowell) very kindly shared this terrific tale of two football playing authors whose athletic careers brought them to the playing fields of Lowell, Massachusetts. Jay can be contacted at JJGiiiLaw@verizon.net

Copyright, James J. Gaffney III, 2012

LOWELL’S “OTHER” FAMOUS FOOTBALL PLAYING AUTHOR.

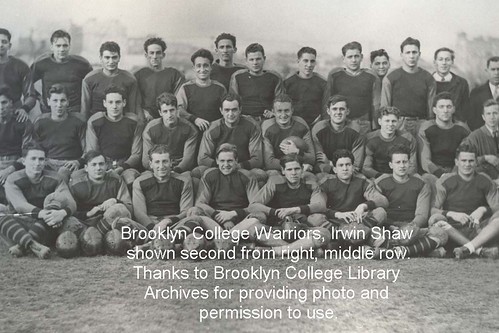

Lowell can turn up in unexpected places. For me, one surprise encounter was reading Rich Man Poor Man author Irwin Shaw’s short story, God on Friday Night. Lamenting the hardships of his solitary travels, Shaw’s main character, Sol the comedian, says “I’m a man who has to play in cheap nightclubs in Philadelphia, and Lowell Massachusetts and Boston. Yuh don’t know how lonely it can get at night in Lowell Massachusetts”. (Decades P.90) * Another surprise was learning that Jack Kerouac was not the only famous gridiron author who dug his cleats into Lowell turf. Irwin Shaw played his football for Brooklyn College, but on two cold fall afternoons in 1932 and 1933, Shaw and his Brooklyn College Warriors (Yearbook P.207) brought their game to Textile Field and Alumni Stadium to take on the Lowell Textile Millmen.

In Lowell, Kerouac is the name which football playing writers usually brings to mind. His football exploits were part of the Kerouac legend along with On the Road and the Beat Generation. His 1938 game winning touchdown against Thanksgiving Day rival Lawrence High led to expectations of football fame which could have been the stuff of a pretty good legend by itself. As described in the October, 1989 Sports Illustrated Article: “Before he met Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs; before his cross-country jaunts in drive-away Chevys and empty boxcars; before the jazz, the dope, the manic prose and finally the fame; before he became tormented by the success he sought and drank himself to death; before all that, Kerouac was, purely and simply, a football star.”(SI P.1)

Kerouac’s football career got off to a slow start. He didn’t see much playing time until his senior year – even then spending a lot of time on the bench. He wasn’t even on the field to start of the famous Lawrence game. (Angel P.26) The Lowell Sun called him a “situational player.”(SI P.3) His sporadic playing time generated some heated local debate. Coach Keady called him a “climax runner” (SI P.2, T&C P.72) secret weapon held in reserve for critical game situations – possibly a PR ploy to quiet the “we want Kerouac” chants from the stands. One of Lowell lore’s go to sources, Father Armand “Spike” Morrisette, thought Keady was one of those rigid coaches who “when he had his mind made up on a lineup, that’s the way it stayed” (SI P.6) Kerouac’s father Leo, as portrayed in The Vanity of Duluoz always suspected skullduggery afoot and blamed “payoffs” for keeping his son on the bench. (Vanity P.171)

The undersized Shaw’s situation never attracted any conspiracy theory attention – he barely made his Madison High School team and never got off the bench. (Shaw P.29) After graduation, Kerouac’s football career seemed poised to build on that Lawrence game touchdown. Columbia (Vanity P.23) had outbid BC and Notre Dame for his gridiron services. His next stop – as a self described “ringer” (Cassidy P.168) was Horace Mann Prep School where Coach Lou Little sometimes stashed red shirt prospects (Angel P33). Kerouac led that team to an undefeated season and City Championship. (Sub P.46) His freshman season at Columbia got off to a fast start “probably the best back on the field’(SI P.7) until it was ended by a broken leg in his second game (SI P.8, Sub P.52). Returning for his sophomore year, he found himself languishing on the bench again. Lou Little had compared Kerouac to Sid Luckman, (SI P.1) but praise didn’t translate into playing time, and, by now, the old Lowell High perseverance was gone. When the 1941 season opened with Kerouac on the bench, he quit – the team and then the school. He drifted back to Lowell, did some sports writing for the Lowell Sun and signed on for a wartime Merchant Marine hitch dodging German U-boats to bring munitions to England.(Angel 52.)When his ship returned, the flame of football glory flickered briefly – only to fizzle out in another playing time dispute. Little sent Kerouac a telegram urging him to rejoin the team for the 1942 season (SI P.8, SubP. 65). When he showed up, Kerouac, once again, mostly sat. Kerouac wanted to get in against Army so he could show up old Lowell High rival and now Army team captain, Hank Mazur. (Angel P.59) When the game ended with Kerouac stuck on the bench, he walked again – this time for good – off on the first steps of his literary journey with its famous milestone, On the Road.

No Frank Leahys or Lou Littles recruited Shaw. In the winter of 1929 he became a subway commuter to Brooklyn College – not yet fielding a football team – or even accredited. Like Kerouac, Shaw took his next year off-. In his case after flunking Calculus. A year of night classes, part time jobs and ambitious self assigned reading got him readmitted in the fall of 1930, the same year that Brooklyn hired Coach Lew Oshins to start a football program. Shaw’s bigger size after the year off and prior, even, if limited, experience was enough to get on this starting from scratch team which held its early practices in a basement.(Shaw Pgs.33-39) On October 15th, 1932 The Warriors, also known as the Kingsmen or Maroon and Gold (Yearbook Pgs.207-208)) traveled to Lowell Textile Institute’s Textile Field to take on the undefeated Millmen coached by Rudy Yarnell. The Starting lineup published in that Friday’s Lowell Sun listed Shaw at fullback.

Lowell Textile Institute

Jarek LE

Forsyth LT

Burke LG

Connolly C

Cowan RG

Welch RT’

Bogacz RE

Curtin QB

Savard LHB Cpt

Athnas RHB

Jurewicz FB

Brooklyn City College

Handler RE

Sirutis RT

Goldberg RG

Holstein C

Greene LG Cpt

Knigin LT

Glickman LE

Krans QB

Berstein RHB

Stainslaw LHB

Shaw FB

The Friday Sun gave Shaw some pregame publicity as a “terrific Punter” an important skill in the days where teams often punted on first down. The 25 to 0 Shut out by Lowell gave Shaw plenty of work in this area. On the Lowell side of the ball, the offense featured backs that “ran like gazelles or smashed the line like battering rams” Captain Aimee Savard was the “Alpha and Omega” (Citizen 10/17/32) of the Lowell attack, scoring three touchdowns including a seventy three yard end around.. One of Shaw’s best and his own favorite (Shaw P.112) short story was called The Eighty Yard Run. The subject was different, but Savard’s scamper could have inspired the title of this story written just a few years later. The Sunday New York Times did report it as an “eighty yard dash”. Shaw and his Kingsmen were back in Lowell the next year for a rematch. The November 11th, 1933 contest was the second half of a double header at Alumni Field. The Line ups in the Friday Sun showed Shaw moving to Quarterback.

Lowell Textile Institute

Bogacz LE

Forsythe LT

Burke LG

Connolly C

Welch RG

Baranowski RT

Grossman RE

Curtin QB

Athanas LHB

Bassett RHB

Griffin FB

Brooklyn City College

Dvorkin RE

Derfia RT

Kristall RG

Salermo C

Gottscho LG

Green LT

Handler LE

Shaw QB

Simels RHB

Rup KHB

Glickman FB

Savard’s graduation didn’t provide much relief. Lou Athanas, memorialized in the Costello Gym entrance as “perhaps the best athlete to ever play” at UMASS Lowell, used his passing and running skills to lead several trips into the Brooklyn red zone, but its defenses stiffened when backed up against their goal line, and the game sputtered to a scoreless tie in “almost total darkness.” (Sun 11/11/33) (See also NY Times 11/12/33). Shaw was credited with completing one of two flea flicker type passes he attempted. (Citizen 11/11/33) The other could have been the missed touchdown pass in Shaw’s list of regrets at the end of his 1984 Playboy memoir. (Playboy)

Kerouac’s serious football playing days were still several years away when Shaw came to Lowell. In 1932, Kerouac had just moved to Phebe Avenue in Pawtucketville and spent time with his friends on Textile Field, sometimes playing pickup games while Yarnell’s charges scrimmaged. He may have even seen Shaw play as part of the crowd watching “shrill keen afternoons of ruddy football” through the Textile fence.(Sax P 52) Shaw never had to face Kerouac, but the Millmen, also known as the “Moody Street Boys,” (Sun 11/11/33) gave Shaw and his teammates all the Lowell legend they could handle. In the ninety seven years from the time that Lowell Textile Institute fielded its first team in 1905 to UMASS Lowell’s final 2002 season, sixteen football players were named to the UMASS Lowell Hall of Fame. Five of them were in Lowell Starting line ups facing Shaw and the Warriors: Savard and Athanas, Tackle John Baranowski, End John Bogacz, and Halfback Lou Basset.

Another Lowell Legend, Ray Riddick, started at Left end for Lowell High in the double header opener against Rindge Tech. (Sun 11/10/33)

Shaw’s gridiron career wasn’t launched with Kerouac fanfare, but he was a four year starter and played some pass the hat type semi pro football for several years. (Shaw P.55)Even after Shaw’s playing days ended, the writer never left the football player behind. It followed him like an old friend. He enjoyed the ex football player references. His three broken noses (Shaw P.39) helped him look the part – as well as sticking him with“the nose” nickname in college. (Yearbook P.207). Some of his stories March, March on Down the Field, Whispers in Bedlam, and Full many a Flower, (Decades) and the play Easy Living were football specific. His fiction tough guys were often former football players. His 1965 Esquire Magazine tribute to YA Tittle and the New York Giants gave him another chance to stake his own claim to membership in the football fraternity and return to “autumns now thirty years in the past” (Tittle P.33) Football always remained a fixed star in Shaw’s firmament. On a trip back to Brooklyn College to address a Poetry class, he described writing as a “contact sport.”(Decades P.xi)

Kerouac’s friends later wondered “if he was ever as happy as he was on the football field,” (SI P.4) Football’s place in his later life was more complicated. He described his Columbia walkout as “the most important decision of my life so far. What I was doing was telling everyone to go jump in the big fat ocean of their folly”(Vanity P.93) “the hell with these big shot Gangster football coaches, go after being a writer” (Vanity P.92) but Kerouac’s walk out was more than a disgruntled benchwarmer telling his coach to “take this game and shove it” Kerouac was already questioning Football’s significance in a world swept by war. (Sub P.45) He had thought of being “a college football star” but also or being “a great scholar — and of being a great man eventually” (T&C P.72) decision finally became “so simple, so simple’ quit football, stick to my studies, stick to the human things.”(T&C P.263) He later said he “gave up football for Art.”(Sub P.207)

Like Shaw, Kerouac sometimes reached back to football for the right analogy to some of his experiences – sometimes it came with a swagger – when telling William Burroughs “You can’t just walk on the Shakespeare squad” (Sub P.94). Other references were less creditable. He related using a “quarterback sneak” (Sub P.154) to get out from under a barroom thrashing, and, later, that he “snucked out like a football player” (Sub P.347) to escape student demonstrators after defending the Vietnam War at the University of Naples. During his Buddhist studies phase, he saw football in conflict with the non violence of Eastern teachings and blamed bouts of Phlebitis on bad Karma from football brutality (Sub P.240). Shaw, on the other hand, often indulged some macho pride in the game’s “ferocity” and speculated notoriously, even if tongue in cheek, that “If the players were armed with guns, there wouldn’t be stadiums large enough to hold the crowds” (Tittle P.212).

The post gridiron days of authors lives veered off on different trajectories. The Jet Setter Subterranean contrast is a oversimplified but still tempting one when thinking of Shaw’s yacht and his residences in the Hamptons, Paris, Antibes, his Chalet in Klosters Switzerland, and his social milieu of what he called the “Beautiful People of the International Set” (Nightwork P.117).Shaw was reported to have “at least eight sets of friends” (Burning P.214) and guest lists included the A Lists of the entertainment and literary worlds on both sides of the Atlantic. On the literary side were almost all of that times best selling main stream authors. The show business contingent included Ingrid Bergman, Debrah Kerr, Frank Sinatra, Leonard Bernstein, and Kirk Douglas.(Shaw Pages 14,146,207, 294) Shaw started making money almost right out of college writing radio scripts and a succession of best sellers followed by television serialization of Rich Man Poor Man.

Kerouac never made any money off his trade until his advance from On The Road in 1959. He had survived on a few pick up jobs and what he could scrounge off family and friends. He once borrowed $10.00 from John Holmes promising repayment from “Memere’s” next paycheck (Sub P.132). His friends had to take up a fifty five dollar collection to retrieve a broke and stranded Kerouac home from a trip to Mexico. (Sub P.220) When On The Road. hit the bookstores, he enjoyed an interval of prosperity sustained by the rapid succession publication of most of his other works. He became a homeowner, owning houses in New York, Florida and Sanders Avenue in what biographer Ellis Amburn called the “fashionable Highlands” Lowell neighborhood. (Sub P.348) Kerouac had his own celebrity associations, notably William F Buckley, Cole Porter, and Gore Vidal. (Vanity Pgs.56,58) He enjoyed Park Street dinners and Poetry Jazz collaborations with Steve Allen, (Sub Pgs.301,288) but he himself said that he preferred the “rattling trucks of the highway to the drawing rooms of Noel Coward” (Angel P.126)- The “rattling trucks” were really a metaphor for the non conformist margins of society and literature he inhabited most comfortably. As time went on the “rattling trucks” morphed into neighborhood bars and, by the time he died, he had come full circle mostly subsisting mostly off Memere’s Social Security and coming back empty handed from trips to the mailbox looking for royalty checks that never came. (Sub P.369)

Both men were heavy drinkers. Shaw’s social life revolved around drinking and its effects became more severe as the years went on. He was sometimes seen circling back to the restaurant table to finish the others’ drinks when his group was leaving.(Burning P.223) He knew the toll it was talking, (Shaw P. 342) but when asked why he didn’t quit, replied only “I can’t” (Shaw P.368) In Kerouac’s case, there wasn’t much doubt that the booze killed him. The Thomas Wolfe admirer (Angel P.45, Vanity P.92) was known to consume Wolfian quart a day quantities of hard liquor (Sub P.308) and rivers of beer. Alcohol and drugs sometimes got some credit for his spontaneous prose, but it was inspiration with a heavy price. He later described his life as “getting drunk waiting for friends and getting drunker when they showed up.”(Sub P. 331) Alcohol was involved in some of his worst humiliations. It led to getting him ordered out of Lowell High by Coach Riddick when he did a drunken sub stint for another teacher.(Sub P.359) He was ridiculed after a boozy speaking engagement performance at Harvard (Sub P.328) and viewed nationwide drunk and “nodding off” on William F. Buckley’s Firing Line (Angel P.338) Lowell neighbors told stories of Kerouac trying to bum liquor and wandering around trying to peddle a manuscript for $20.00 to raise bar money. (Sub P.349) He never recovered from the effects of a severe beating in a Florida Bar when he could no longer call on the legs which had eluded tacklers and carried him out of earlier scrapes,(Sub P.371) and the booze finally dragged him down into the vortex of a death spiral which ended with his fatal 1969 hemorrhage in Florida

Some of Kerouac’s final football memories echoed with past grievances.– the bitterness in the “I saved your school once against Lawrence” protest to Riddick on his way out of the High School, (Angels P.333) and a 1969 postcard to Charles Sampas, weeks before his death, was still picking at the scab left by watching the Army game from the bench. (Sub P.371)

Shaw’s later life football memories seemed to have the warm autumn glow of a late afternoon stadium. He once showed up, a little tipsy, for a dinner invitation carrying his autographed football. (Shaw P.377) When screenwriter and protégé James Salter went to Shaw’s downsized Klosters apartment right after his death, he remembered the Brooklyn team picture prominently displayed among the diminished possessions. (Burning P.229) Salter’s Life intersected with both gridiron authors. He was a sub on Kerouac’s Horace Mann team and remembered the “swaggering Lowell boy” (Burning P.30) football ringer who wrote articles for the literary magazine. Shaw enjoyed being a player and ex player so much that he probably wasn’t displeased when a New York Times review of one of his plays described him as a “third rate professional football player”, (Shaw P.81) – even if he had known that Kerouac’s two freshman games and some sophomore scrimmages at Columbia had one rival Ivy League coach calling him “the best halfback” in the world. (Sub P.66)

God on Friday Night was published in 1939 and Shaw’s treatment of Lowell won an O’Henry Competition third prize. In the glow of his Shaw’s football memories, something about those games in Lowell shone. There seemed to be more than just football tugging at his memory. He spent the summer of 1940 in Falmouth and could have traveled back to Lowell again (Shaw P.57) Thirty five years after Shaw picked Lowell as a place for journeymen comedians to spend lonely nights, Lowell showed up again in his novel Nightwork where Shaw introduces us to Miles Fabien, war hero turned international hustler of the rich and famous with roots as the son of a Lowell shoe factory hand. Lowell was mostly portrayed as an unpromising starting point for a journey which brought Fabian’s charm and affected British accent to Europe’s ritziest watering holes. The Lowell references included the customary “If they could see good old Miles Fabian in Lowell Massachusetts now” (Nightwork P.174) while celebrating a race track win with caviar at a Riviera Bistro. Another one of the eight Lowell references came down hard on the city. His partner is saying “Come on now, I remember you come from Lowell Massachusetts”, and Fabian retorting “and you come from Scranton Pa –and we should both do our damndest to forget the misfortunes.” (Nightwork P.286) There is food for speculation about why Shaw put Lowell on the tour for journeyman comics. There were real Sols in the City on those weekends. Place like the Merrimack, Gates, and RKO Keith’s theatres ran stage and screen double features showing movies and live vaudeville. Why did the loneliness of Lowell hit Shaw’s Sol so hard? Kerouac knew loneliness in Lowell even if his loneliness came from his soul as much as the Streets. Did Sol, like Kerouac, step out of a theatre into the “phantom griefs of life in the Lowell Streets.” (Cassidy P.116) – or was Sol just giving himself a pass for bad behavior on the road. Harder to figure was Shaw’s put down of Fabien’s blue collar mill town background considering his own immigrant background (Shaw P.22) and brushes with poverty growing up in New Jersey – and his playing for a college founded to serve “—children of immigrants, working-class New Yorkers” (Brooklyn Web) – just as many children of immigrant and working families in Lowell turned to Textile for their education opportunity. Could Shaw have just been indulging an author’s prerogative for payback in print? Even though the 1933 tie was seen as a slight upset, Shaw and his teammates in the “Four Hawksmen” (Shaw P.39) backfield were looking back on eight tough quarters of football without scoring a single point. Still, the Lowell connection in his writing seemed much deeper and more complex than just the football.

If there is autobiography in Fabian, Shaw may have just projected the ambivalence of later years reflection on his own journey through life. When it counted Shaw had the Lowell in Fabian coming through. Fabian dies throwing himself in the path of a bullet fired by a masked gunman during a robbery attempt. Fabian passes off his heroism- “Maybe it was just a little bit of old Lowell, Massachusetts sticking out.” (Nightwork P. 312).

A few years later, and not long before he died, Shaw was with James Salter reminiscing about football —and especially about football in Lowell. Shaw remembering a final goal line stand “playing in Lowell, the earth hard as cement, the ball on the two yard line, them with first and goal.“ (Burning P.225) Shaw, born Shamforoff, (Shaw P.22), the son of Russian Jews, playing safety and keeping a wary eye on Athanas, (Athanasopoulos) the Greek from the Acre. (Blackhawks). Looking over the line at the Moody Street boys, did he see some of himself looking back?

When Fabian’s partner told him that they wouldn’t find a trace of Lowell in him “if they went in with drills” He responded “you’d be surprised” (Nightwork P.203) and true to his word, the master of the St Moritz gaming tables looked to the Lowell in him at the end – the same City where Irwin Shaw directed many of his own backward glances including some of his final ones.

FOOTNOTES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: I am indebted to Brooklyn College and UMass Lowell for assistance along the way. All of my contacts were knowledgeable, resourceful – and generous with their time (and possibly patience),

Edythe Rosenblatt Assistant Archivist, Brooklyn College Library Archives and her staff going above and beyond to provide materials and information to help a cold calling Lawyer with an off the wall writing project

Similar assistance and helpful cooperation came form The UMass Lowell Group:

Chris O’Donnell, Director of Athletic Media Relations.

Heather Makrez Director of Alumni Relations, and staff.

Martha Mayo and Janice Whitomb, Mogan Center

My assistant Kathleen Martin was a big help in getting the final version into presentable format and keeping this article from submerging the rest of the office.

.

NOTE ON SOURCES: All sources should have been referenced in at least one of the footnotes. The Shnayerson book was an excellent biography and main source for general Shaw biography fact background. The Amburn and McNally books along with the autobiography running through Kerouac’s own work were similarly good resources for Kerouac biography. The Sports Illustrated Article (great on Lowell people who were part of Kerouac’s football life) and Vanity of Duluoz were the other main Kerouac football references. Game account information came mostly from the Sun, Courier Citizen, and Times articles cited. It was an incidental and unrelated reading of Salter’s book, a fascinating memoir, which first tipped me off to Shaw’s connection with Lowell.

SOURCES:

Irwin Shaw Short Stories: Five Decades, Delacorte Press/New York 1978 (“Decades”)

Brooklyn College Yearbook (Yearbook) 1934

Mike D’Orso Saturday’s Hero: A Beat. Sports Illustrated. October 23rd,1989 SI Vault,(“SI”)

Jack Kerouac The Town and The City (“T&C”) A Harvest Book, Harcourt, Inc.1970.

Jack Kerouac Vanity of Duluoz , Penguin Books P17(“Vanity”) 1964

Michael Shnayerson Irwin Shaw a Biography (“Shaw”) G.L. Putnam and Sons, 1989

Jack Kerouac Maggie Cassidy (“Cassidy”) Penguin Books, 1993

Dennis McNally Desolate Angel, Jack Kerouac, the Beat Generation, and America (“Angel”). De Capo Press 1979

The Lowell Sun

Lowell Courier Citizen

Irwin Shaw. Playboy Magazine, January, 1984 What I’ve learned About Being a Man Jan.1984

Jack Kerouac Dr. Sax, Grove Press,1959

Irwin Shaw, Tittle Fading Back,(“Tittle”) Esquire magazine, January 1965

Irwin Shaw, Nightwork, Dell Publishing Company, 1975

James Salter Burning The Days (“Burning”) Vintage International, 1997

Brooklyn College Web Site, “About” Section Our Past, Our Future

The Blackhawks In Lowell Charles Tsapatsaris Web Article (Blackhawks)

I do not think Shaw was in any way small by the time he entered college.When the cofounder of Random House Bennet Cerf first met Shaw when he was 22 or 23 years old he said Shaw looked like a burly longshoreman. No question Shaw’s drinking became impossible for him to control and probably led to an early death. Shaw appeared on a book program and was interviewed by Robert Cromie. I was shocked to see his face and behavior. He answered questions in a very hazy manner. He is my favorite short story writer and you should read the collected stories,superb and memorable. He did say that he never wrote with a drop of liquor in his system but claimed that a few drinks brought on fresh ideas. There is one story “Tip on a dead jockey” one of my favorites.He never wrote a careless sentence.Best,Edward