My TED Talk

Thanks to the UMass Lowell Honors Ambassadors program, the first TEDx Lowell event was held yesterday at UTEC on Warren Street. It was a great event, well-organized and interesting and all because of the great effort of the UMass Lowell students who ran the entire show. I was privileged to be one of the 18 speakers who took the stage yesterday. Everything was recorded by LTC for eventual posting to the TEDx YouTube channel. In the meantime, here is the text of the remarks I delivered:

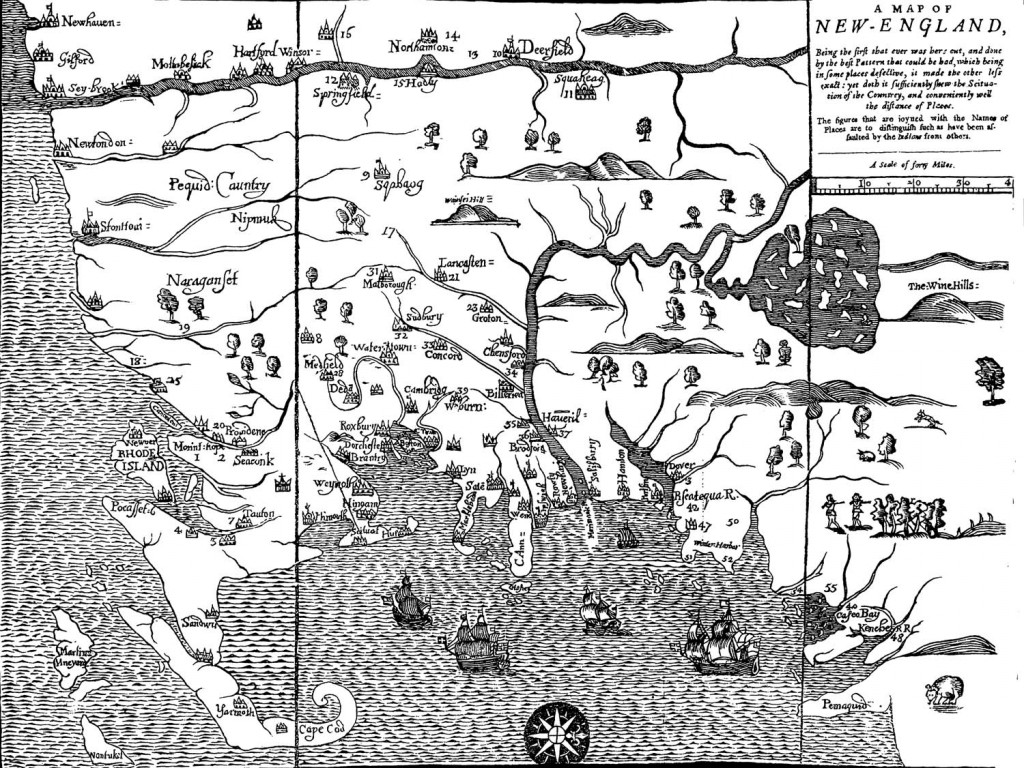

In 1677, William Hubbard published a book in Massachusetts that contained the first map of New England that was actually printed in America. Once you get used to the fact that on this map, east points towards the bottom and west towards the top, you notice that two terrain features really stand out. They’re both rivers: the Connecticut and the Merrimack. That’s not surprising because from the earliest settlement of the English colonies in North America, their survival was in many ways dependent on their ability to trade goods from the interior forests like furs and timber with England and other overseas destinations. As the highways of 17th century America, big rivers were the only way to get these items to the seacoast for shipment to England.

But the Merrimack River was flawed as a transportation route. Originating in the White Mountains, the Merrimack flowed south and then east to the Atlantic. Soon after its turn to the sea, the river dropped 32 feet in less than a mile that began at a place called Pawtucket Falls. Goods being shipped from the interior to the sea had to be unloaded from boats, carried on land past the Pawtucket Falls, and then loaded on other boats for the final leg of the journey to Newburyport. It was very inefficient but for nearly a century and a half there was no alternative.

In the aftermath of the Revolutionary War, people across the northeast embraced what they called internal improvements and what that we would call transportation infrastructure. Such was the case along the banks of the Merrimack. On June 27, 1792, the Massachusetts General Court allowed the petition of Dudley Tyng, Joseph Tyler and their associates to incorporate as the Proprietors of the Locks and Canals on Merrimack River for the purpose of constructing such canals and locks as were necessary to bypass the obstacles to navigation on the Merrimack.After four years of work and $50,000 of expenditures, the Pawtucket Canal opened for business in 1796. It left the Merrimack above the Pawtucket Falls and swung in a broad arc through East Chelmsford for a distance of a mile and a half, finally flowing into the Concord River just short of its confluence with the Merrimack. The Pawtucket Canal used four lock chambers to handle the 32 foot change in elevation between the two rivers.

The Pawtucket Canal was an immediate success but the legislature had granted only a corporate charter and not a monopoly and so on June 22, 1793, the General Court granted a corporate charter to the Proprietors of the Middlesex Canal. This canal, which left the Merrimack a mile upstream from the entrance to the Pawtucket Canal, sliced 27 miles southward through Middlesex County until it reached the Charles River and Boston Harbor. Although the Middlesex Canal did not begin operations until 1804, it quickly became the preferred transportation route which caused the Pawtucket Canal to struggle financially and eventually cease operations.

The Pawtucket Canal lay unused for more than a decade until a group of entrepreneurs arrived on the banks of the Merrimack in November 1821 and decided they could use the Pawtucket Canal for another purpose. These men were known as the Boston Associates. They included Kirk Boott, Nathan Appleton and Patrick Tracy Jackson. They were colleagues of Francis Cabot Lowell, the visionary who first imagined a great American industrial city but who died before he could see his dream become a reality.

Born in Newburyport in the same week that the British marched out to Lexington and Concord to begin the Revolutionary War, Francis Cabot Lowell was the the son of a prominent lawyer. Rather than pursue the law as a career, Francis set himself up as a merchant/trader in Boston and at a young age made a fortune importing goods from the Orient. Always in precarious health, in 1810, Francis Cabot Lowell traveled to England for a two year vacation. There, he became fascinated by the emerging textile industry. Scrutinizing the machinery and business practices used by the British, Lowell imagined that he could do better.

Returning to America in 1812, Francis assembled a team of mechanics, managers and investors who together constructed the first all inclusive textile mill in America on the banks of the Charles River in Waltham. The mill was an immediate success. There was an insatiable demand for domestically produced cloth and investors received a 25% return in the first year of operation. Everyone clamored for expansion. The problem was that the Charles River dropped only 6 feet, producing insufficient hydro power to run more mills in Waltham. A new site was needed. Before it could be found, however, Francis Cabot Lowell died at age 42 of consumption. That was 1817. His dream didn’t die with him and that’s what brought Kirk Boott, Nathan Appleton and Patrick Tracy Jackson to the banks of the Merrimack in 1821.

Satisfied that the Merrimack River produced all the hydro power they would need and pleased with the bonus of the already constructed Pawtucket Canal, they quietly bought the stock in the Locks and Canals corporation, giving them ownership of the canal and more importantly, control of the water that flowed through it. They also bought the sparsely settled farm and pasture land on either side of the canal and on the south bank of the Merrimack. They widened and deepened the Pawtucket Canal and in 1823 the Merrimack Manufacturing Company, the first of the great mills at this site went began producing cloth. The rapid expansion convinced the mill owners that the existing town government of Chelmsford was inadequate to handle the needs of the mills and their workers and so they petitioned the state legislature to grant them a charter for a new town. They called it “Lowell” after their departed friend and mentor. The city grew rapidly. On the eve of the Civil War the city’s 52 mills were turning 800,000 pounds of cotton into 2.4 million yards of cloth each week. Presidents and celebrities were drawn to Lowell to see the first planned industrial city in America. Lowell also became a magnet for those with talent, energy and drive making the city the Silicon Valley of 19th Century America.

And it was all because of a failed business venture, the Pawtucket Canal. While Lowell has certainly had its ups and downs in the 190 years since its founding, this ability to take a failed business venture and repurpose it for another use has been a constant. We’re surrounded by recent examples.

Back in the early 1990s, changes in the computer industry caused Lowell-based Wang Labs to falter. Its headquarters, the Wang towers, which cost $60 million to build, was sold at a foreclosure auction for $525,000. The new owners, backed by an innovate use of city planning funds, soon landed NYNEX as an anchor tenant and the towers rapidly filled with new businesses. Wang’s bankruptcy also caused the abandonment of its six-story training center in the heart of downtown but imaginative leaders at Middlesex Community College gained ownership of the building and made it the center of the school’s city campus. Sitting just across the Pawtucket Canal from the Wang Training Center was the Hilton Hotel, built in downtown on the promise of housing Wang’s trainees. The computer maker’s bankruptcy sentenced the hotel to decades of high vacancies and high losses for its owners. To Marty Meehan, the Lowell native and newly installed Chancellor of UMass Lowell, this failed hotel was a great opportunity for the University to expand its presence in downtown and so was born the UMass Lowell Inn & Conference Center which houses students, hosts events and has enlivened the center of the city. The building we are in right now was an old church that was empty and unused for decades until UTEC acquired it for the organization’s headquarters and in the process turned it into one of the most energy efficient buildings in Massachusetts.

The lesson of Lowell is this: Just because a venture fails, doesn’t mean that it’s a failure. It just means it’s an opportunity to try something else. That’s the lesson of Lowell.

A wonderful read. I would have loved to have been there.