Lowell: Producing Urban Public Space and City Transformation

In the following chapter from his urban theory book Exploring the Production of Urban Space, author Michael Leary-Owhin visited Lowell and wrote about the creation of Boarding House Park.

Lowell: Producing Urban Public Space and City Transformation

By Micheal Leary-Owhin

… countries in the throes of rapid development blithely destroy historic spaces – houses, palaces, military and civil structures. If advantage or profit is to be found in it, then the old is swept away . . . Where the destruction has not been complete, ‘renovation’ becomes the order of the day, or imitation or replication or neo this or neo that. In any case what had been annihilated in the earlier frenzy now becomes an object of adoration. (Lefebvre 1991: 360)

So I get there and they’re telling me all about the design and they said we’ve only got one problem. I said what’s that? We don’t own the land. I said, you don’t own the land and you’re designing a park. And they said, we have money to acquire it. So they were spending money on design. Shortly after it [the parking lot] was appraised at $535,000, we had the money to make the purchase and they had $2 million to build it [the park]. So it was a pretty sad looking parking lot. I said, well how are you doing to get the land. And the staff said, that’s your job. (Peter Aucella 2012a research interview)

Introduction

A welter of frenzies of destruction was wreaked upon Lowell for several decades until the 1970s. Coincidentally, just when Lefebvre’s The Production of Space was published in the first French edition, the mood changed to one of historic adoration in Lowell. A pinnacle of this adoration was the designation of the Lowell National Historical Park (LNHP). It is the quality of Lowell’s downtown urban public spaces which in large measure provide for the social relations which make the park work successfully in multifarious ways. It was the fusion over three decades of a city based civic ethos with state and federal public spiritedness, which facilitated the enhancement of existing and the production of new urban public space in Lowell. The purpose of this chapter is not so much to recount the history of the national park, that has been accomplished several times and there are several published accounts of it emergence (Gall 1991; Ryan 1991; Stanton 2006). The story of Lowell’s post-industrial revitalisation continues to fascinate researchers and recently useful contributions have been made by and Weible (2011) and Minchin (2013). Undoubtedly, the most comprehensive history of the national park to date is the NPS sponsored Marion (2014a).

Although it is necessary to present brief details of the genesis of LNHP, this is done only to situate and complement the presentation of new research insights which privilege a different set of protagonists and issues from those which tend to frame the dominant academic narrative. The naming and renaming of space and place are critical moments in the production of space. Places not named are “holes in the net”, they are “blank or marginal spaces” (Lefebvre 1991: 118). Prominent protagonists in the struggle to establish the national park had implicit understanding of the salience of establishing credible representations of urban space. Rather than rehearse national park history in any more than brief summary, an alternative aim of this chapter is to focus on how the range of interests which promoted LNHP, did so partly through attempts to impose a meaningful name through which they could gain leveraged to appropriate and define its objectives. Lefebvre’s spatial framework should be borne in mind, particularly as analysis of the three case studies presented in the second half of the chapter unfolds. In each case as with the case studies in the other chapters, the state and each of its constituent institutions were involved deeply in the production of space. Additionally, what becomes apparent is the involvement of other actors and agencies across the private, not-for-profit and community sectors. The cases are based on three public space projects: Kerouac Park, the Canalway and Boarding House Park. They allow examination of the coalitions, interactions and challenges facing the production of inclusive urban public space.

…

Soul of Lowell: Boarding House Park

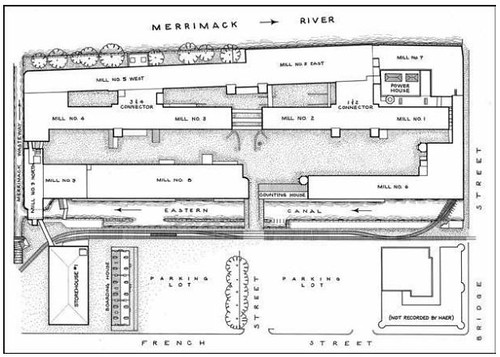

It is perhaps entirely appropriate that in a city founded, planned and built by industrial capital, the dominant civic public space should showcase, not city hall but the city’s most iconic mill complex. Boott Mills is justly famous for being the most intact textile mill complex in the US. Built in phases which mirror the expansion of the city, it constitutes not just a physical record of industrial growth in Lowell from the 1830s to 1900, but provides insights into important steps, “in the growth of American industry, technology, water power generation and scientific management” (Bahr 1984). The first mill buildings were built close to the riverbank and as more were added through the decades, eventually the complex of nine buildings formed a large enclosed millyard. In front of the mill complex the Boott Mills Company built six, three story boarding houses, set at right angles to the mills, to provide accommodation for the Yankee Mill Girls. Five were demolished in the 1930s leaving the westernmost building the only survivor (figure 5.6). Paradoxically, the loss of these historic buildings provided the opportunity for the production of what was destined to become the most auspicious public space in Lowell – Boarding House Park. The project brought together a range of LNHP and LHPC objectives, particularly the relationships between historic preservation, the cultural remit and public space aspirations. Although PL 95-290 and the 1977 Brown Book identified particular buildings and structures where preservation and adaptive reuse were urgent, it did not specify particular cultural events or festivals that would be encouraged and supported nor crucially, did it envisage the creation of new public space where such events might take place.

PL 95-290 required LHPC to produce a draft ‘Preservation Plan’ within one year and certainly before any major preservation or cultural grants could be awarded. In 1980 the final version of the LHPC Preservation Plan was published. It illustrated and explained how LHPC would achieve its major goals around three themes: preserving the 19th century setting, encouraging a variety of cultural expression and pursuing historic restoration projects mandated by PL 95-290. Clearly, cultural programmes were to be as important as physical preservation. Staff at the LNHP had a keen understanding that public space whether it is: streets, canalscape, parks or city squares needed to be animated with activity. With this in mind, the Preservation Plan provided specific substance to the rather vague cultural aspirations of the Brown Book. Five site-specific projects were identified because, “they best combined preservation and cultural objectives“ (LHPC 1980: 40), including what was called ‘Boott Mill Park’. The Preservation Plan was clear there were two aspects to its cultural remit. Firstly, to prioritise the historical aspects of Lowell’s industrial development and the role of ordinary workers in that development. To this end the LHPC would, sponsor cultural programs and projects that, “use Lowell’s significant structures as the setting in which the people of Lowell can tell their own story” (LHPC 1980: 3). Secondly, LHPC prioritised its wider cultural remit in terms of the valorisation of Lowell’s ethnic diversity. In order to encourage cultural expression LHPC would:

… initiate a variety of projects and programmes. These will include support of ethnic festivals, educational programmes to portray cultural diversity, counselling in obtaining grants, scholarships, neighbourhood preservation grants, and creation of a multicultural centre within the park. (Ibid)

Figure 5.6: The Last surviving Boott Mills Boarding House

Figure 5.6: The Last surviving Boott Mills Boarding House

In an audacious civic-minded move, LHPC promised to, “create a new civic open space” (Ibid: 46) to be called Boott Mills Park. It was envisaged that the park would link the activities of the downtown commercial area with a proposed cultural centre/museum (to be housed in the remaining boarding house) and Boott Mills. Intriguingly, the 1980 Preservation Plan contained a remarkable visualisation of how the completed park might look (figure 5.7). Regarding social interaction, the Plan proposed both a passive recreational area and a stepped open air performance centre, forming a terraced amphitheatre. In that sense it is reminiscent of the Castlefield Arena (see chapter seven). On the one hand this was a bold proposal, on the other, it should be seen as part of the continuing project whereby new public space in Lowell is created and animated by social and cultural activities. While these are all important purposes for public space, I argue these production of space processes reveal the ingenuity and resilience of civic minded, public spirited intervention.

Although the idea of an outdoor theatre in downtown Lowell in 1980 seems innovative, this was not the first time this idea was mooted. Attention has already been drawn to the Southworths’ 1973 proposal for a Boott Mill Cultural Center. It specified that the Center would see the conversion of the millyard into a “festival courtyard”, that would be the site for “ethnic art, music festivals, as well as outdoor performances in warm weather” (Flanders 1973). It is worth noting that many LHPC minutes of meetings and reports refer to the proposed adaptive reuse of Boott Mills as the Boott Mill Cultural Center. The importance of the one acre site that became Boarding House Park cannot be overestimated. This derived partly from its downtown location and its being flanked to the north-east by the magnificent Boott Mills. Challenges were presented by its sloping topography and its being flanked to the north-west by the sadly decrepit Boott Mills’ boarding houses, still displaying the livery of the H&H Paper Company. In addition, the public space of the park was to be connected into the trolley system with a stop at the Boott Mills by the Eastern Canal. Obviously, this combination of factors complicated the task of creating a new public space. More importantly though the project faced an even greater encumbrance, highlighted by Peter Aucella earlier – the privately owned site was in active everyday parking lot use.

Figure 5.7: How Boarding House Park might look

Aucella joined LHPC as executive director in 1986. Over the next few years he became instrumental in seeing the Boarding House Park project implemented. Although Aucella evidently has a penchant for the melodramatic, as the quotation at the head of this chapter demonstrates amply, the crux of his sentiments is valid. His background in urban planning, project management and his keen appreciation of city politics unquestionably provided a welcome fillip for what was to become the Boarding House Park project. Certainly, the 1980 Preservation Plan gave high priority to the creation of a significant new public space in front of Boott Mills, but little progress was made on this project until 1986. Fortuitously, not only did Aucella have the skills and experience to tackle the complex new park project, he also knew the owner of the parking lot:

Well fortunately once again Paul Tsongas a few years earlier had called me up and said there’s this guy named Ed Barry who is working at mills in Lawrence Massachusetts, he’s a client of our law firm, and other people in the law firm brought him to me and said, he should really be looking at Lowell. Paul said, so Peter would you give him a tour of the mills in Lowell. So I went to see him and said here’s what the Commission wants to do. He said I think that would be fabulous but I’ve got one little problem I own 810,000 square feet of space [Boott Mills] and that’s my only parking lot. (Aucella 2012b)

Barry was understandably reluctant to part with the parking lot. Although it occupied a prime downtown location, in the mid-1980s the site for the proposed Boarding House Park was integral to the operation of Boott Mills, which at this time still provided space for hundreds of workers in a variety of commercial enterprises. Aucella explained what happened next, in an intricate deal involving: LCC, the state, the HUD, LHPC, LNHP and Barry’s company, Congress Group Properties. Across the street from the parking lot was the John Street parking garage: a rather ramshackle affair with a shoddy one floor deck above the surface lot. Apparently, LCC aspired to redevelop it into a thousand carparking garage, but did not have the requisite $10 million. In effect, Barry was offering to swap the surface parking lot for a new parking garage built on the John Street lot. Aucella took the deal to the city manager Joe Tully, confirming that LHPC would build the new downtown Boarding House Park and performance space for $2.5 million. Site acquisition would see Barry paid half a million dollars for the Boott Mills parking lot, but things grew more complex:

I went to the city manager and said, we’ll build a $2.5 million performing arts centre here if we can figure out how to get this land. So we are going to pay him $535,000, my recommendation is we have him endorse the cheque to the city as payment for the broken down parking garage site. He’ll renovate that as part of the financing for the whole project. But my advice is you take the $535,000 and don’t just put it in the bank for the city, you put in a special fund to design a new parking garage. The city manager loved it. (Aucella 2012b)

That still left the city needing $10 million to build a new parking garage on John Street. Fortuitously, in the 1980s Massachusetts had an off street parking programme providing 70 per cent grants towards the cost of parking garages. LHPC and LCC convinced the state to award a grant. That was the last grant ever given in Massachusetts under the parking garage programme. With $3 million still outstanding, the city was able to secure a $1 million grant from HUD. So the city paid $2 million for a thousand car garage – an impressive piece of civic initiative.

Turning now to Boarding House Park, a design competition was initiated and three architectural practices shortlisted. In May 1985 the contract to design what was by then known as Boarding House Park was awarded to Brown and Rowe Landscape Architects, which was and is a ‘woman owned business’. They would do the overall landscape design, with Rawn Associates engineers designing the steelwork for the performance pavilion. The creation of a new public space on this slightly sloping one acre site in downtown Lowell threw up a number of competing objectives set by LHPC. A major priority was to create a covered performance space and a seating area for several hundred spectators. Another was to memorialise the cotton industry and its workers. In addition, the new park was meant to provide an attractive low key setting for and access to the rehabilitated Boott Mills and the soon to be reconstructed Boott Mills boarding house cultural centre. On top of that, the new space was meant to be a place where residents, workers and visitors would want to spend time informally.

It is therefore easy to appreciate how LHPC’s objectives for the project, the professional aspirations of Brown and Rowe and the budget constraints caused some tension throughout the design and implementation phases. Chrysandra Walter of LNHP was perturbed about how the various objectives of the brief were being prioritised. In a lengthy critique of the early design proposal she offered some support but pulled no critical punches:

Several significant problems remain with this plan, however. Most of them stem from the fact that the design’s attention to the needs of a performance area have subordinated other critical agenda items. One of the most important of these is the need to serve park visitors and pedestrians by providing visual and circulation links between the restored boardinghouse and the Boott Mills complex. These links are essentially diagonal, whereas the present designs orientation is along the north–south axis features to stage, rather than the historic buildings. A row of trees effectively screens off the boardinghouse façade from the Park, instead of using the Park to feature this beautiful, restoration. (Walter 1986)

Brown and Rowe accepted most of these criticisms but remained steadfast regarding the trees in front of the boarding houses. Towards the end of the construction phase another issue of disagreement provoked a protracted exchange of correspondence. Brown and Rowe wanted to have the final say about the colour of the pavilion steelwork: red was their preference. This may seem a rather trivial matter but it sheds light on how the private sector was regarded in the design stage:

For the record, the color has always been tentatively a dark (NPS), green, or possibly a black. Chuck Parrott has explained to Mr. Rawn that one of his considerations in the color decision is the wishes of our abutting neighbor to the Park, Congress group properties, who are in the process of a $60 million development of Boott Mills. (Wittenauer 1989)

Clearly, Wittenauer the LHPC construction supervisor and Parrott felt that the interests of the developer Congress Group Properties needed to be given due weight in this decision and one can only speculate as to if and how Ed Barry influenced other design decisions for Boarding House Park.

In addition to the park and performance pavilion, a public art series was brought to fruition by LHPC. Sculptor Robert Cumming won the competition and designed a series of high quality textile industry themed polished granite sculptures, funded partly by the National Endowment for the Arts and located at the corners of the park. Cumming wanted people to touch them, walk on them, sit on them and he mused that the sculptures were, ”like brand-new sneakers that come out of the box a little too white” and he “wouldn’t even mind seeing a little gum stuck to Francis Lowell’s nose” before the summer is finished (in Francis 1990). In other words, he wanted the people of Lowell, including the children to use their imagination to make the park part of their everyday life. One critic thought the “playful sculptures reflect spirit of Lowell” (Unger 1990).

Despite a range of impediments and controversies the park was completed within budget and on time. Painted in NPS dark green, the performance pavilion creates an impressive focal point for the park, which was designed to seat 1,700 or 2300 standing, in a sloping amphitheatre. It was opened officially in June 1990. In attendance at the dedication ceremony were state attorney general James Shannon, Congressman Chester Atkins and former Senator Paul Tsongas. He said at the official opening that the park and the public art will provide an aesthetic boost to the city and, “I think what is out there will be considered the new soul of Lowell” (in Francis 1990). It is somehow fitting too that a Tsongas obituary starts by giving prominence to the park he helped create:

When he stood in the raindrops at Boarding House Park, Paul Tsongas spoke of embarking upon his “journey of purpose” to become the President of the United States. We in Lowell knew better… For Citizen Paul Tsongas, his journey to make his city and his world a better place began as soon as he was old enough to make a difference, and continued – with as much passion and purpose as ever – until it ended all too soon Saturday night. (The Lowell Sun 1997)

Over the years, the park has hosted many wonderful large-scale events and provided space for the tactile appreciation and quiet contemplation of Lowell’s industrial past. Its multifarious attributes were recognised by the prestigious 1995 Federal Design Achievement Awards as a delightful example of civic architecture which encourages the kind of vigorous public life that is essential in a democratic society (Alexander 1995). That may well be so, but Boarding House Park also facilitated, inadvertently, the production of inclusive, differential space in Lowell discussed in chapter eight.

Fascinating that the state used to finance parking garages at .70 cents on the dollar. It’s too bad the parking lot to the east of Boarding house park still hasn’t been developed, as in the sketch, to better frame the park and provide more housing and tax revenue for the city.

Jeff Speck had some nice drawings for that parcel as well.