“Large Bottles and Sweet Butter Pastry” by JULIE WARD

Guinness Storehouse at St. James Gate in Dublin is often listed as Ireland’s number-one tourist attraction; but here on Trasna there’s no admission fee to learn the history of bottling the world’s most famous pint.

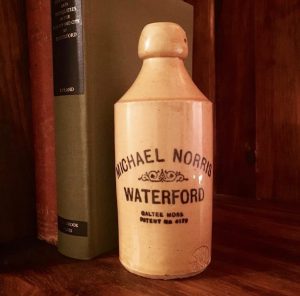

“Glass on wood is likely among the first sounds I heard,” writes Julie Ward in this rich remembrance of her father, Bob Phelan, the man who, it was said, poured one of the best pints of Guinness in Waterford. The pub was known as Mikey Norris’s, it went back to Ward’s great-grandfather, and is known to this day as Norris’s Corner. As a child Julie also treasured visits to local confectioner Suzie Phelan, a woman whose loosely bunned hair appeared to be “made only of flour”, and made observations far beyond the tempting confectionery.

More than a sensory remembrance, however, Ward’s essay urges readers “to stay connected to where our food comes from,” and to those who make it.

“Large Bottles and Sweet Butter Pastry” by JULIE WARD

It is no surprise to me that my two earliest childhood memories relate to food and drink.

It was the late sixties, and growing up over a busy family pub and grocery in the south eastern Irish city of Waterford meant all hands on deck. My father, like many other publicans at that time, was still bottling the iconic large bottle of Guinness on his own premises and I, the youngest of five children, was of course keen to help.

He wore a full-length brown oilskin apron over a grey wool suit, crisp white shirt and muted tie. His shirt sleeves were carefully folded back and held in place by elasticized metal bands. On occasion, he would allow me, aged no more than three, to help.

With the flat serrated bottle cap, picked from a box of thousands, clenched firmly in the palm of my small hand, he would carefully instruct me to place it on the cap receiver plate. “Stand back now,” he would say with great command as he firmly lowered the large metal arm down to connect the recently filled stout bottle with the cap, the serrated edges now bent tightly hugging the bottle. Removing it carefully from its secure nest, he would then guide my hand to place the bottle in the crate. This act was repeated until the crate was full. Later, when I started school, I didn’t need to learn how many was in a dozen; I already knew.

After two crates or so, he would tell me to run along. He had possibly eighty dozen to bottle that day, one of three bottling days each week. I didn’t mind, I was happy; I had seen the magic performed again.

As the decade of the seventies rolled in, it was clear that the practice of local bottling would come to an end. Guinness’s were making it clear: they wanted bottling centralised, mechanised, and standardised. The weekly stout barrel deliveries, horse drawn up Summer Hill’s steep incline from Plunket Railway Station, would soon be a thing of the past. Not however without significant resistance from many provincial publicans.

Labour intensive and a huge consumer of time, the lengthy bottling process was a source of tremendous pride for the publicans who gloried in all its elements. Although they knew it inevitably would go, none were going to allow the label displaying the family name on the bottle disappear without a good fight, and my dad was no exception.

Of course his resistance did not make him popular with the man from Guinness’s, but the enormous volume he sold meant he held the cards for a little longer than they would have liked. We like our large bottle in Waterford to this day; but in those days, a large bottle off the shelf was an institution, the name on the bottle they chose a mark of honour, a measure of quality in the house and indeed the skill of the publican and his men.

When it did end some short years later, my father wasn’t happy but he accepted it. He knew when a battle was over, and this one was over. The large bottles no longer bore the name over the door, Michael Norris, but he continued to take pride in receiving them, storing them in rotation, each one carefully wiped with a damp cloth before it was placed on the shelf each morning. As a responsible ten-year old, I was tasked with this important job each Saturday morning and received 10 pence for my work, an absolute fortune.

The change was a subject he returned to over the decades that followed, and even in his last years he still talked about some of the anger he felt at the time. He was never a fan of Guinness’s afterwards and went out of his way to support the smaller breweries, something he may have passed on to his children.

As time passed, draught Guinness became more popular, and the younger generation viewed the large bottle as the drink of their fathers. The weekly cleaning of the beer lines, done unfailingly each Monday morning, was no chore to Dad. In an elaborate network of tubes that travelled from the keg to the pouring tap, a cleaning solution circulated like an intravenous medical drip flushing all in its path. Any stout residue that thought it had found a comfy home here was in for a quick shift. It was often said that Norris’s poured one of the best pints of Guinness in Waterford. My Dad could only take their word for it; the man never took a drink in his life!

My Dad’s pub had its counterpart in a treasured bakery. “Suzie’s,” as it was known locally, was a cake shop on one of the main streets in Waterford. Owned and run by confectioner Suzie Phelan, a formidable woman whose loosely bunned hair in my memory was made only of flour, had trained many a girl to bake and, though she was stern, the girls all revered her.

Trips to Suzie’s were special occasions. Always long anticipated and prized when they happened, the visits were redolent with the rich, warm smell of pastry, cream and sugar, a buffer to any grey winter day outside. Stretching high onto my four-year-old tippy toes to gaze in awe through the polished cake display glass, the worries of my small world weighed heavy on my shoulders as I tried to decide which cake I would choose when my mother finally finished relaying news of her sister Breda, a novice nun in New Zealand, who had worked for Suzie before she left.

There was every type of cake to choose from: enormous cream sponges, filigree iced custard vanilla slices, small iced fancies, but the ones that fascinated me most were the seasonal ones. Depending on the time of year and what was in season, we could find fresh berry tarts in summer, snow covered, tinsel trimmed cakes and mince pies at Christmas, Simmel cake at Easter with uniform toasted almond icing, the twelve almond paste balls carefully gracing the outer edge. On seeing me so entranced, my mother would once again explain the religious symbolism of the Simmel cake, the twelve balls representing the twelve apostles. She would voice this lesson slightly louder than needed, to announce her ecclesiastical prowess to all. She was good that way.

Cakes chosen, we would be ushered up a steep set of narrow wooden stairs to the sitting area. The tea and the cakes were presented on delicate china and placed on the light table, which, in company with the unsteady chairs, I feared would be the end of my cake some day.

The girl serving us seemed a beauty transformed when away from the business side of the shop and the scrutiny of Suzie’s watchful gaze. She had worked and was friends with Mum’s sister Breda, and news of Breda in New Zealand brought such a change in her manner it was almost impossible to concentrate on the much prized and as yet untouched cake.

There had clearly been a true friendship between the two women; even as a very young child I could see the delight in this woman’s whole being as she heard tales of life on a continent too far away from her own to imagine.

Even religious life seemed brighter than life in Waterford she would joke, adding each time that of course it would with “Breda’s fun and sunshine ways.” We would leave with messages of love, news, and regard to be included in the next letter to Auckland. Eating at Suzie’s was not just about cake and, as young as I was, I knew that.

Food and drink has been an integral part of my life ever since, and I’ve worked in the field in many guises. In recent years I started working with wine, a subject I once had only modest knowledge of but one which offers much for a person who wishes to read, learn, and drink of course, but most of all to listen. The beauty of the online world means you can now be in a vineyard, a bodega cellar, a Solara, and hear the voices and practices of those who have gone before the present generation and know that those same practices and voices will be valued by those yet to come.

The sound of wine bottles reaching the shelf is a soothing one; glass on wood is likely among the first sounds I heard, maybe even before I joined this world. I know I am lucky to have this connection with the past and I value it.

Like the seasonal gooseberries that lay encased in sweet butter pastry in Suzie Phelan’s or the pride that was felt by my father in the quality of the stout that rested under his bottle label, we must stay connected to where our food comes from; so that those who produce it can do so with care, cause no harm, and receive a fair price for their work.

Julie Ward is a native of Waterford in Ireland’s south east. A mother to two boys she works as Food and Wine Customer Advisor in Ardkeen Quality Food Store, Waterford, who specialise in Irish artisan & locally produced food. Her writing explores food and drink heritage and happenings in Ireland. She is a wine contributor to the Business Post newspaper. Julie is active on Twitter @JulieWard_ and on Instagram @julie.wardwaterford

Enjoyed this glimpse into the past from Julie.

So evocative and I adored ” the sound of glass on wood “.

Thank you.

That was a smashing read Julie. Thank you.

yes i remember it well ,there was quite a difference in taste between the different bottlers Bobbys and i think Madigans were regarded as the best and i think Savage Smiths the worst some pubs would have bottles of stout from different bottlers and you would have to specify which one you wanted

Wow Julie that was a beautiful read of times gone by. I could almost taste Susie Phelan’s pastries. “Glass on wood” love it. Congratulations on your wonderful insight of Waterford.

Loved this story julie well done

and so wtitten beauitfuily.best wishes for the future.

Loved this piece, Julie. Beautifully written and so evocative of the times.

Lovely account of the life and times of a past generation.

Well done Julie beautifully written of such wonderful memories ❤️

So beautifully written , I could almost see the pastries and taste the pints but I did not want the story to end .

Keep them coming Julie , you are such a talent

Well done julie Brillant and beauitful memeorys to have .

A wonderful read Julie, bringing me right back to a childhood of fond memories.❤️