George Charrette, Lowell Medal of Honor recipient

George Charrette, 1867-1938

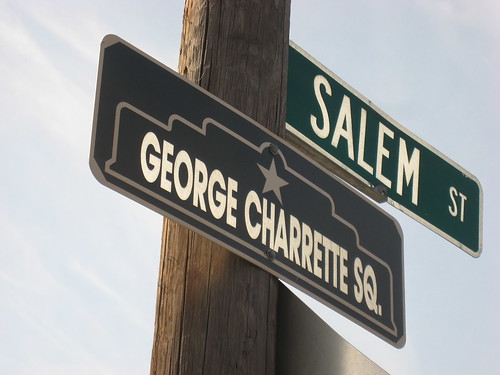

The streets of Lowell are dotted with hundreds of small black signs located near road intersections. Each sign bears a man’s name: some who died in war, others who performed heroic deeds or provided long and faithful service in the military or to the community. Of all the signs in the city, however, the one that represents perhaps the most dramatic achievement, a story that exceeds in excitement and daring the best of historical fiction, is the one located at Salem and Pawtucket Streets that bears the name George Charrette.

Original Charrette Square marker

In June 1898, George Charrette was a gunner’s mate on the USS New York, the flagship of the US Navy squadron under the command of Rear Admiral William T. Sampson that was hunting the Spanish Caribbean Fleet. Seeking to avoid battle with the more powerful American navy, the Spaniards fled to Santiago Harbor, a large port with only a narrow opening to the sea that was protected by numerous forts and gun emplacements.

Unable to draw the Spanish fleet out to sea, Sampson devised a bold plan that would send a stripped down US ship into the narrow harbor channel where it would be scuttled by its volunteer crew, thereby closing the channel and trapping the Spanish fleet in the harbor. To command this hazardous mission, Admiral Sampson selected a young officer named Richmond Pearson Hobson and gave him command of the USS Merrimac, a steam powered cargo ship built in Norway in 1894 and purchased by the Navy in April 1898. Despite the difference in spelling, this ship was named for the river that passes through the city of Lowell.

Hobson planned to sail the Merrimac into the channel in the dark of night, turn it sharply to one side and simultaneously ignite what he called “torpedoes” that be placed along the side of the ship beneath its waterline. These torpedoes were more like massive pipe bombs; 18-inch wide metal canisters filled with gunpowder that would be ignited by electricity, a novel and not completely reliable detonation technique in 1898.

In response to a request for eight volunteers for this mission, nearly every sailor in the fleet stepped forward. For the critical task of detonating the explosives, Hobson chose Charrette who had extensive experience with gun powder and who had previously served with Hobson on another ship.

On the appointed night, Hobson, Charrette and their seven comrades donned life jackets and pistols and set out for the harbor on what many considered a suicide mission. As they raced into the harbor channel at full speed, the Spanish fortress gunners spotted the Merrimac and poured sustained and heavy fire into the ship. As the Merrimac approached the narrowest part of the channel, Hobson shut down the engines and ordered the helmsman to turn sharply to starboard. While the wheel on the bridge turned, the rudder did not: it had been shot away as had most of the torpedoes. Only two exploded and the resulting holes in the side of the ship were too small to instantly sink the ship. With the anchor shot away, there was no way to halt forward momentum and the Merrimac slid to the side of the channel, finally settling on the bottom clear of the main shipping path.

Amazingly, all nine Americans aboard not only survived, but had escaped all injury. They plunged into the water and were rescued the next morning by Spanish soldiers. Out of respect for their demonstrated bravery, the crew was well treated by their Spanish captors and just a few days later were turned over to the advancing American Army.

For their heroism, George Charrette and the eight others who sailed the Merrimac into Santiago Harbor that night were awarded the Medal of Honor. While still imprisoned in Cuba, Charrette was promoted to Gunner (a Warrant Officer rank). For the rest of his Navy career, he alternated shipboard assignments with time ashore, mostly at the Charlestown Navy Yard. He was promoted to Lieutenant in 1917 and retired in 1925 at age 58. He lived the rest of his life in Lowell, dying on May 7, 1938 at age 70. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

George Charrette grave, front

George Charrette grave, back

Charrette Square marker, 2009

Charrette Square marker, 2014

Thank you, this was very interesting. Years ago I used to work at St. Joseph’s and passed that sign almost every day. Never knew this man’s story & now I do!

What is also amazing is that he was 5′ 4 and 3/4 inches tall.