John Lawlor, Philip Conway, Boston University and the continuity of a proud Irish athletic tradition … by Dr. Tom HUNT

For the month of July here on Trasna, we have been highlighting some of the literary and artistic events cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The other significant arena of cancellations due to COVID-19 is, of course, sport. Today we present an article by Irish sports historian, Dr. Tom Hunt, who focuses on the early history and impact of athletic scholarships from Boston-area universities, on the world of Irish athletics.

~

Irish athletics was rescued from international oblivion by the USA scholarship system. The trail began in London in 1948 with the superb performance of Jimmy Reardon in the 400m at the Olympic Games which alerted USA officials to Irish talent. In London, Reardon and his colleagues John Joe Barry and Cumin Clancy chatted to two USA athletes, George Guida and Browning Ross, who were students at Villanova. The American system of awarding college scholarships to talented athletes formed part of the conversation. Reardon was the first to benefit from this conversation and in 1949 he became Ireland’s first scholarship athlete when he accepted an offer from Villanova. Clancy and Barry followed the same path and the Villanova Pipeline, as the trail of Irish athletes to the college was known, was activated. Ronnie Delany was the fourth Irish athlete recruited and thrived in his new athletic and academic environment. Ronnie, a brilliant winner of the 1956 Olympic 1500 metre title at Melbourne, proved that the USA scholarship system worked. His coach Jumbo Elliott and Villanova became part of the vocabulary of Irish sport.

John Lawlor and Philip Conway were part of one of the great traditions of Irish athletics: they were men who threw weights for distance as a recreational activity. Irish emigrants, affectionately known as The Whales, John Flanagan (1900, 1904, 1908), Matt McGrath (1912) and Paddy Ryan (1920), won the first five Olympic hammer throwing titles; Martin Sheridan (discus and shot put) and Pat McDonald (shot put, 56lb weight) also won Olympic titles representing the USA.

Dr Pat O’Callaghan continued the trend in 1928 and 1932 when he won the hammer throwing title representing Ireland.

Since 1949, the bartering of athletic talent for a college education was part of the fabric of Irish athletics and a recent head count has identified 194 female and 486 male track and field athletes who have availed of scholarships in colleges in practically every state in the USA. Up to the mid-1970s in Ireland, a university education was a privilege reserved for the elite of Irish society. The trickle to the USA of the 1950s became a stream in the late 1960s, and continued unhindered until the mid-1990s. In 1987, between 100 and 110 athletes, were on scholarships in forty-one colleges across the USA. In the Boston area, Harvard, Boston University (BU), the University of Massachusetts at Lowell and Boston College have all awarded scholarships to Irish athletes who possessed the required athletic and academic credentials.

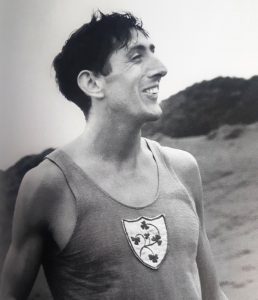

Hammer thrower, John Lawlor, a member of the Irish police force, began the Boston trail in September 1956 when he enrolled in BU. While on the beat in Dublin, Lawlor was known to practise his turns on the confined spaces of the doorways of the streets of Dublin. Encouraged by Brendan O’Reilly, a scholarship student at Michigan State, Lawlor contacted a number of American colleges and outlined his credentials. BU responded favourably. At twenty-two-years of age, Lawlor exchanged the lifestyle of a Dublin city policeman for that of a student of geology at BU, where he prospered both academically and athletically. The reputation of hammer coach Ed Flanagan influenced his decision to attend BU.

Lawlor thrived in the new environment. He set a college record for 27 consecutive victories in the hammer. In 1958, he became the first Irish hammer thrower to break the then magical 200-foot barrier and he won two NCAA hammer titles (1959-1960). His induction to the BU Track and Field Hall of Fame in 1969 confirmed his status in the college. The Olympic Games were staged in Rome in 1960, the finest year of Lawlor’s athletic career. He produced his personal best throw of 65.18m at Bakersfield, California on 24 June 1960 at the US championships. In Rome, on 3rd September, John Lawlor became the last Irish athlete to compete in an Olympic hammer throwing final. His best throw of 64.95m (213′ 1″) secured him fourth place in an extraordinary competition in which the first eight throwers broke the Olympic record set in Melbourne. He also represented Ireland in the 1964 Games at Tokyo.

John Lawlor also prospered academically and received the E. Ray Speare Memorial Award as Scholar-Athlete of the Year in 1960; he was also voted into the Scarlet Key, one of the highest academic honours on offer at BU. After graduation, John worked in Ireland for some years but returned to BU in September 1965 and completed his Ph. D studies and was employed at Pioneer Asset Management in Boston. As the company’s head of natural resources, John travelled the world from Papua New Guinea to Eastern Siberia to develop investments in oil and gas, precious metals, diamonds and timber.

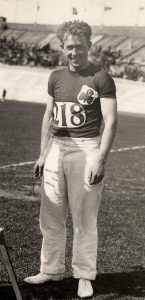

Philip Conway was the second Irish weight events athlete to enrol at BU. Philip was educated in Rockwell College, County Tipperary and was then employed as a clerical officer with the Irish Lighthouse Services. Athletic ambition and advice from Fr Lavelle, his school’s coach, focussed Conway’s mind and his thoughts turned to the USA and the possibilities of securing a scholarship was explored. A list of colleges was obtained from the USA Embassy and BU was included in the list of those contacted. The basketball staff in BU didn’t recruit in 1966 and a scholarship valued at $2,100 for room, board and tuition was awarded to Philip Conway. In August 1966, he paid £66 for a seat on board a Shannon Rugby Club charter flight to the USA where Sidney Poitier and Frank Sinatra were two of the first people he saw on stepping on to USA soil. Welcome to the New World!

Philip Conway, who had never experienced a formal P.E. class, studied the subject in BU, a discipline that had yet to reach its embryonic stage in Ireland and like John Lawlor he thrived in the new environment. Representing BU, he was the winner of fourteen major championship medals in the shot put and discus, the most prestigious of which was a shot put silver medal in the IC4A championships of 1970; a then personal best of 55′ 7¼” secured the New England Inter-Collegiate title. He had no doubt about the reasons for his improvement in Boston. In an interview with The News in March 1970 he explained that ‘I attribute my improvement to the guidance and patience of Coach Leverson [BU weight coach], my accumulation of knowledge in the event, and to the weight lifting programme I worked on. I also am grateful to John Lawlor for his advice and to Coach Billy Smith [BU head track coach]’. John Lawlor was a supporting presence for Philip Conway during his time in Boston. Conway graduated and returned to Ireland in 1970 and was employed as a teacher in Rockwell College. He returned to Boston in 1971 and enrolled in a two-year Masters in Education postgraduate course in Springfield College. In 1972 he represented Ireland in the shot put competition at the Olympic Games in Munich.

Philip Conway returned to Ireland in 1973 and began a teaching career at Belvedere College, imbued with the spirit of an evangelist. The need to revive the culture of hammer throwing in Ireland became a priority. The neglect of the event had been acute and interest in Ireland was minimal. He returned from a place where John Lawlor was accorded legendary status but was a forgotten man in Ireland. Philip Conway was responsible for establishing a school for throwers that assembled every Saturday morning at the UCD campus at Belfield. Before the 1970s ended, a remarkable transformation in hammer throwing had taken place. Conway, the evangelist, wrote to over fifty schools in an effort to recruit as many potential throwers as possible. The initiative played a central role in the promotion of a culture of throwing excellence and students from a variety of backgrounds availed of the coaching and training opportunity. Arduous physical training was combined with work on technique. Conway’s own career path enabled him to present a vision of attainable athletic and educational goals to young athletes that were complementary. Throwing excellence provided an opportunity for career advancement, and from the mid-1970s, over forty throwers travelled to the USA on scholarships over a twenty year period.

Irish throwers became a significant presence on Irish Olympic teams between 1980 and 2000: in this period ten different weight-event athletes competed in the Olympic Games; in the period 1952-1976, John Lawlor and Philip Conway were the only Irish athletes to qualify for Olympic competition in the throwing events. Hammer throwers, Conor McCullough and Declan Hegarty were two of those who were guided by Conway and became scholarships athletes at BU. Hegarty, in 1984, and McCullough, in 1984 and 1988, represented Ireland in the Olympic Games. The scholarship, Hegarty explained ‘allows you to train in an athletic environment. It gives you free room and board. It gives you a free education at third level. It gives you a coach who is paid full-time to watch you every day’. And it worked to the extent that Hegarty’s best throw of 77.80m set in California in 1985 is still the Irish national hammer record. The scholarship also provided Hegarty, a milkman’s son from Dublin, with career opportunities that were rarely available to children from a working class background in the Ireland of the time. After graduating from BU, Declan Hegarty taught science for five years in the Californian Public Schools system. Then with the goal orientated mind of the competitive athlete, Hegarty returned to medical school and now practises as a general surgeon in Inverness, Florida. Conor McCullough’s hammer throwing son, also Conor, has added a new strand to the tradition. He won silver and gold medals at the 2008 and 2010 World Junior Athletics Championships and competed at the 2016 Rio Olympic Games representing the USA.

And it all began with the ambition of a serving policeman, John Lawlor, to master the technicalities required to throw a 16-pound metal ball as far as possible.

Dr Tom Hunt is a native of Clonea, Carrick-on-Suir, County Waterford and is one of Ireland’s leading sports historians. He holds a Ph.D. degree in history from De Montfort University, Leicester. His main research interests are in the history of Irish sport and the contribution of the Malcomson family to the industrial history of nineteenth century Ireland. He is the author of Portlaw, County Waterford: Portrait of an Industrial Village and its Cotton Industry (2000), Sport and Society in Victorian Ireland: the case of Westmeath (2007), The Little Book of Waterford (2017) and The Little Book of Irish Athletics (2017). He has contributed chapters to Sport and the Irish: histories, identities and issues; the Gaelic Athletic Association, 1884-2009 and The Evolution of the GAA, Ulaidh, Éire agus Eile. He has also contributed to history journals in the USA, Great Britain and Ireland and has completed researching and writing the history of the Olympic Council of Ireland.

Photos: various sources, courtesy of Dr. Hunt

Excellent and informative thanks Tom

I enjoyed the thorough look at Irish Olympic connections with US schools, especially with BU, where I taught for a number of years, and I was happy to learn of the successful careers of the athlete-scholars.

You’ve given us a window into a fascinating subject Tom, and I suspect there is much more to be written on this.

Thank you very much for this wonderful article. I was impressed at how you focussed on how many of these athletes used the american scholarship system not only as a springboard for their athletic development, but as a launchpad for success in later life. Philip Conway always emphasised “you cannot eat a hammer”!

Great article Tom.