Lowell Week in Review: January 18, 2019

Charter Change

“Executive Session – Regarding matter of litigation, namely Huot, et al, v. City of Lowell, public discussion of which could have a detrimental effect on the city’s position.”

The above item appears on the agenda for this week’s Lowell City Council meeting. The same item was on the agenda for last week’s meeting and for the December 18, 2018 meeting. On the only other day the council has met since then – January 8, 2019 – the council had an entirely separate special meeting on the same topic, also in executive session.

Huot, et al, v. City of Lowell is the lawsuit pending against the city in the U.S. District Court in Boston. A group of Lowell residents has sued, alleging that the current method of electing city councilors and school committee members violates the Federal Voting Rights Act by diluting the votes of minority members of the community. The gist of the complaint is that with our vote-for-nine, winner-take-all system of electing councilors, 51 percent of the voters control 100 percent of the council seats.

The case has been pending for nearly two years and most recently was sent to mediation by the court. With the council going into executive session on a weekly basis, I have to assume there is some movement towards settling the case. I also assume that a settlement acceptable to the plaintiffs would require at least a portion of the council to be elected from districts rather than at large.

I believe that the plaintiff’s claim has merit and that the city should switch to a system of representation that has some councilors elected at large and others elected from districts with the districts mirroring existing neighborhood boundaries.

Besides being more equitable, an at-large/district mix might help reverse the diminishing involvement of so many residents in the local political process. Some numbers will help illustrate this point:

- Number of people living in Lowell – 111,000

- Number registered to vote – 60,950

- Voted in 2016 presidential election – 37,346

- Voted in 2018 gubernatorial election – 27,024

- Voted in 2017 council election – 13,916

- Voted in 2015 council election – 10,714

- Voted in 2013 council election – 11,581

- Voted in 2011 council election – 9,946

Why is it that twice as many people vote in a state election than in a city election? And why is it that three times as many vote in a presidential election than in a city election? It’s because a large number of Lowell residents who are already registered to vote and who have proven a willingness and an ability to vote in other elections, are disconnected from city government. We are left with a system that permits 9 percent of the city’s residents to select the nine city councilors who make the decisions that greatly impact the day-to-day lives of the other 100,000 residents of the city.

Councilors will say that they represent everyone in the city and I believe they are sincere in that belief, but I also think they are wrong.

Councilors enjoy being councilors and want to be re-elected. So who will they pay the most attention to: The 10,000 people who regularly vote in city elections or the 100,000 city residents who don’t vote in council elections?

The majority of motions made by city councilors emerge from neighborhood meetings or calls from constituents. The people who attend neighborhood meetings and the people who call city councilors are among the 10,000 regular voters. If someone from the 100,000 non-voting residents were to call a councilor, the councilor would certainly respond, but no one from that group calls councilors because they don’t know who they are, or they’re not comfortable contacting them. That’s because they don’t feel connected to local government.

This exclusionary system gets reinforced with each city election. When council candidates campaign, they often “go door-to-door.” But whose doors do they go to? They go to the people who regularly vote in council elections. They do that because they know those people will vote and they don’t have the time or resources to reach out to everyone in the city. The same thing happens with campaign mailings. A person who votes regularly in city elections will often receive a dozen or more pieces of candidate literature in the days before an election. A person who doesn’t vote in city elections won’t get a single one. And that latter group constitutes 90 percent of city residents.

Some will argue that the problem isn’t with the system, it’s with the people who “don’t bother to vote.” But this argument ignores the structural impediments built into our current system.

In the context of school desegregation cases, courts have long identified two types of segregation. They are called de jure and de facto. An example of de jure segregation would be a local ordinance that said “White children must go to school A and African-American children must go to school B.” An example of de facto segregation would be a local ordinance that said “Children must go to their neighborhood school” in a city in which all the white children live in one neighborhood and all the African-American children live in the other neighborhood. The effect IN FACT is segregated schools. Courts have held de facto segregation to be wrong, regardless of the absence of any overt policy designed to create such segregation.

I think the same principal applies in Lowell City Elections. Consider how the city is organized for election purposes. There are 33 precincts. The boundaries of those precincts are drawn so that each contains approximately 3500 human beings. I use the term “human beings” purposely, because that 3500 include people like children and immigrants who are not legally entitled to vote. So right away, precincts that have fewer children and immigrants – or to put it more bluntly, precincts whose residents are older and whiter – have a larger pool of possible voters than do precincts with more families and more immigrants.

Only after we acknowledge that inequity can we move on to the other two factors: the percentage of those eligible who do register to vote and the percentage of those who register who actually vote in city elections.

We can measure the discrepancy in registered voters on a precinct-by-precinct basis. Lowell’s 33 precincts are organized into eleven wards. The following list identifies each precinct by its ward and precinct number then shows how many registered voters there are in that precinct (based on the 2017 council election) and the city neighborhood in which that precinct is located:

REGISTERED VOTERS

- 1-1 – 1878 – Lower Belvidere

- 1-2 – 2532 – Belvidere

- 1-3 – 2370 – Belvidere

- 2-1 – 1448 – Acre

- 2-2 – 2072 – Acre

- 2-3 – 2650 – Downtown

- 3-1 – 1854 – Highlands/Middlesex Village

- 3-2 – 1858 – Acre

- 3-3 – 1785 – Lower Highlands

- 4-1 – 2115 – Lower Highlands

- 4-2 – 1653 – Lower Highlands

- 4-3 – 2087 – Ayer’s City

- 5-1 – 1856 – Pawtucketville

- 5-2 – 1881 – Pawtucketville/Centralville

- 5-3 – 2138 – East Pawtucketville

- 6-1 – 2212 – Pawtucketville

- 6-2 – 2238 – Pawtucketville

- 6-3 – 2157 – Pawtucketville

- 7-1 – 1714 – Acre

- 7-2 – 2057 – Acre

- 7-3 – 1601 – Acre

- 8-1 – 1875 – Upper Highlands

- 8-2 – 2126 – Highlands

- 8-3 – 2335 – Upper Highlands

- 9-1 – 1995 – Centralville

- 9-2 – 2209 – Centralville

- 9-3 – 2114 – Centralville

- 10-1 – 1850 – Ayer’s City

- 10-2 – 1517 – South Lowell

- 10-3 – 1520 – South Lowell

- 11-1 – 1990 – South Lowell

- 11-2 – 2014 – South Lowell

- 11-3 – 1995 – Belvidere

Now let’s look at the number of people who did vote in the 2017 council election in each of those precincts. The numbers below show the number of people who voted and the turnout percentage:

TURNOUT 2017 COUNCIL ELECTION

- 1-1 – 288 – 15% – Lower Belvidere

- 1-2 – 1472 – 58% – Belvidere

- 1-3 – 1247 – 57% – Belvidere

- 2-1 – 107 – 7% – Acre

- 2-2 – 225 – 11% – Acre

- 2-3 – 417 – 16% – Downtown

- 3-1 – 350 – 19% – Highlands/Middlesex Village

- 3-2 – 253 – 14% – Acre

- 3-3 – 313 – 18% – Lower Highlands

- 4-1 – 487 – 23% – Lower Highlands

- 4-2 – 180 – 11% – Lower Highlands

- 4-3 – 241 – 12% – Ayer’s City

- 5-1 – 353 – 19% – Pawtucketville

- 5-2 – 232 – 12% – Pawtucketville/Centralville

- 5-3 – 397 – 19% – East Pawtucketville

- 6-1 – 560 – 25% – Pawtucketville

- 6-2 – 578 – 26% – Pawtucketville

- 6-3 – 496 – 23% – Pawtucketville

- 7-1 – 240 – 14% – Acre

- 7-2 – 290 – 14% – Acre

- 7-3 – 233 – 15% – Acre

- 8-1 – 329 – 18% – Upper Highlands

- 8-2 – 502 – 24% – Highlands

- 8-3 – 931 – 40% – Upper Highlands

- 9-1 – 280 – 14% – Centralville

- 9-2 – 550 – 25% – Centralville

- 9-3 – 391 – 19% – Centralville

- 10-1 – 321 – 17% – Ayer’s City

- 10-2 – 171 – 11% – South Lowell

- 10-3 – 142 – 9% – South Lowell

- 11-1 – 338 – 17% – South Lowell

- 11-2 – 471 – 23% – South Lowell

- 11-3 – 531 – 27% – Belvidere

There is a narrative in local politics that “Belvidere controls city elections.” The fact that six of nine city councilors live in the two main Belvidere precincts – 1-2 and 1-3 – contributes to that conclusion as does that fact that those two precincts, which represent just 6 percent of the city’s population, cast 20 percent of the votes in the last city council election.

Would changing to a hybrid mixture of at-large and district city councilors increase voter participation? I think it might. People have to feel connected to city government before they will become regular voters. Perhaps having candidates run in a smaller district will motivate those candidates to reach out to those disconnected from local government. Perhaps those same residents, when they see their elected official living in their neighborhood, will be more likely to engage with that elected official in a meaningful way. There’s no guarantee this will improve the situation, but one thing is for sure, if we leave the system as is, nothing will change.

One other thing that’s certain is that if we leave the decision of whether to make a change in our system to the 10,000 people who now control the system, the answer will be to leave things as they are. That’s why Councilor David Conway’s motion for this Tuesday, “Request City Council solicit the opinion, through a ballot question, of the voters of the city of Lowell on whether they want to maintain the city of Lowell’s present municipal election representation or direct the city to develop a new municipal representation for the city” is, at best, disingenuous. The issue before the U.S. District Court is whether or not Lowell’s electoral system fails to represent all residents of the city. The 9 percent of city residents who now vote in city elections think the system works just fine (which it does for them); why would they vote to dilute their political power? Proposing a referendum at this point is a cute way of saying let’s leave things as they are and in no way contributes towards finding a just and equitable solution to this problem.

NOTE: The Lowell Sun has a major story on this same topic in today’s newspaper.

Patriot Care medical marijuana dispensary

Marijuana and Lowell

Retail marijuana was much in the news back in November when the Commonwealth’s first two retail marijuana establishments opened for business, one in Northampton, the other in Leicester. Each day, the Boston TV stations led with stories about the disastrous traffic encountered in Leicester, a small town in Central Massachusetts. Today, either the traffic is under control or the Boston media has lost interest in the issue because we hear nothing more about it.

That same intensity of coverage emerged in Lowell just a few weeks ago, when an outfit hoping to open a retail marijuana shop in a dilapidated building at the corner of Westford and Stedman streets in the outer Highlands held a neighborhood meeting which is one of the preliminary requirements of applying for a license from the state. Outraged residents of the neighborhood swamped the meeting. We learned recently that the opposition has caused the proponent to abandon that site.

That opposition to marijuana lingers in the city and manifested itself at last week’s city council meeting with a motion by Rodney Elliott to impose a moratorium on new marijuana licenses, however, that motion lost by a six to three vote (Elliott, Rita Mercier and David Conway yes; Mayor Samaras, Karen Cirillo, Ed Kennedy, John Leahy, Jim Milinazzo and Vesna Nuon no).

The procedure for implementing this law has been established by state government. It allows three types of marijuana facilities: Those that grow marijuana or make things from it (think brownies with marijuana cooked into them); those that distribute it to people with medical needs for it; and those that distribute it to people for “recreational” uses. In the regulations, there are called (1) cultivation/manufacturing; (2) medical distribution; and (3) recreational distribution.

In May of 2018, the Lowell City Council adopted comprehensive marijuana zoning regulations. These regulations were written to promote cultivation facilities. These would be located in vacant or underutilized buildings or parcels, they also employ the most people at the highest wages, and they don’t attract any customers. The city also explicitly gives preference to businesses owned by women, minorities or veterans.

All marijuana businesses wishing to open in Lowell must appear before the Planning Board. Cultivation and manufacturing business must get site plan review. Dispensary businesses must get a special permit and site plan review. Before going before the Planning Board, all applicants must have a Host Community Agreement negotiated and executed by the City Manager and a security plan approved by the Lowell Police Department.

Right now, there are two marijuana facilities already open in the city, both by a company called Patriot. There is a medical marijuana dispensary at 70 Industrial Ave and there is a cultivation facility at 170 Lincoln Street. At the November 13, 2018 City Council meeting in response to a council motion asking for the extent of public safety responses to the two facilities, the Lowell Police and the Fire Department both reported that calls for their services have been minimal.

While there are no retail marijuana facilities in Lowell now, there is one that’s already been approved, also by Patriot. There are also several other companies pursuing licensing requirements.

The city must have a minimum of five retail marijuana facilities, something determined by the number of liquor licenses in the city. The city council also voted to restrict the number of retail marijuana facilities to that minimum number of five. There is no limit on the number of cultivation or medical facilities.

So that’s where we stand on marijuana in Lowell. In the election in which marijuana was on the ballot (the 2016 presidential election), at total of 37,346 people voted in Lowell. 19,621 voted to legalize marijuana and 15,565 voting not to.

As may have been evident from my above discussion of charter change, I’m not a big fan of government by referendum. Neither am I a fan of funding government by gimmick, like lotteries and big surcharges on marijuana sales. If we want government services, we should acknowledge their cost and be willing to pay for them through our taxes.

That said, we did have a referendum. Marijuana was legalized by a relatively large margin of voters, and the state has no established a framework for administering the cultivation and distribution of marijuana. The law allows these facilities. While the approval process lies heavily with the state, the city does have some local control through the City Manager and the Planning Board. We should pay attention to how both handle upcoming applications, but we should also treat this issue rationally, not emotionally.

Lowell Rally for Women 2019

Lowell Rally for Women 2019

About 60 people gathered at the Ladd and Whitney Monument in front of Lowell City Hall yesterday afternoon for the 2019 Lowell Rally for Women. Speakers included Congresswomen Lori Trahan and City Councilor Karen Cirillo.

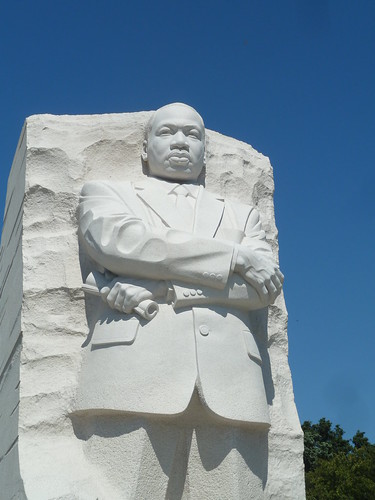

Martin Luther King Jr memorial, Washington, DC

Martin Luther King Jr Day

Tomorrow at noon at the Tsongas Center at UMass Lowell, the Middlesex Community College Foundation and Living the Dream Partners will present the annual Moving the Dream Forward Together event which seeks to connect the Greater Lowell community while honoring the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The event is open to everyone. Donations are welcome.