“Legislating Under the Influence” by John Edward

John Edward, a resident of Chelmsford who earned his master’s degree at UMass Lowell and who teaches economics at Bentley University and UMass Lowell, contributed the following column.

I suggest that we accept the following two principles:

1 – Government must regulate and monitor the sale of alcoholic beverages.

2 – The objective of regulation must be to protect and promote the economic and social well being of the community, not to maximize the profits of the purveyors.

I further suggest that state and local officials are failing with regard to the 2nd principle.

The state has a compelling interest in requiring a license to sell alcohol. No one will sell alcohol without an opportunity for profit. The opportunity for profit comes from participating in a competitive market. In a competitive market the government should not pick winners and losers.

In 1933, the 21st Amendment to the United States Constitution repealed Prohibition and gave states the authority to regulate alcohol. Most states, including Massachusetts, issue licenses to private retail businesses to sell alcoholic beverages. In Massachusetts, the Alcoholic Beverages Control Commission (ABCC) regulates liquor licenses.

The ABCC enforces a quota system for liquor licenses. They limit the number of licenses each community can issue to sell alcoholic beverages. The limits are based on population.

Once a city or town issues a license, the retailer owns it. The retailer can later sell the license to a new business owner at whatever price the market will bear. The city or town and the ABCC must approve the transfer.

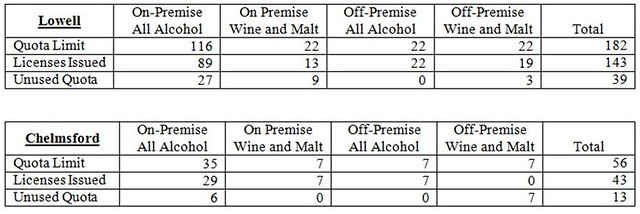

Each community has a limit on the number of businesses where alcohol will be consumed on-premise, for example restaurants and bars. There is a separate limit for off-premise sales, for example package stores. For both on and off premise sales there are distinct limits for all alcohol licenses and licenses that allow sale of only wine and malt (beer).

Based on data provide by the ABCC, here are the quota numbers for Lowell and Chelmsford. An “Unused Quota” is the number of licenses not currently owned by a retailer and therefore available for issue by the city or town.

In both Lowell and Chelmsford there are no off-premise licenses for selling all alcohol available. One license broker is currently listing only 2 off-premise all-alcohol licenses statewide. They list one license at $125,000; the other says call for details. Sometimes licenses sell for a lot more.

Economists call a market with few competitors that enjoy extensive control an Oligopoly. Much like taxi medallions in Boston, the liquor licenses are scarce so they become very valuable. It is good to be an oligopolist.

In Lowell, three license types are available. In Lowell, there have been some bad incidents recently at drinking establishments. In Lowell, there is unlikely to be a push to expand the quotas any time soon.

In Chelmsford it may be a different story. In Chelmsford there are only 6 unused licenses for on-premise alcohol.

Many restaurants need a liquor license to succeed. Evidence from Chelmsford supports that claim. The ABCC recently denied a license transfer approved by the town because the previous owner owes the state money. The new restaurant serves good food, but does terrible business because it cannot sell alcoholic beverages.

The Town of Chelmsford is working with a developer to promote commercial expansion in Chelmsford Center. There is also a committee creating a plan to revitalize North Chelmsford Center. There have been discussions regarding zoning changes to allow restaurants along Route 129 as amenities for one of the town’s business districts. If these plans are successful they will increase the number of restaurants and the demand for licenses.

These economic development efforts may fail if the town runs out of liquor licenses for restaurants. That is why the town should back an initiative to give communities more flexibility, and control, in issuing liquor licenses.

Although Cambridge has no cap on liquor licenses, and other communities are asking for the same, simply raising the limit should suffice. Chelmsford should have the ability to expand commercial opportunities. Lowell would not have to issue new licenses. Carlisle can maintain their status of only one issued license. Dunstable can stay dry.

In addition, new licenses issued should be non-transferable. The town, not the business owner, should “own” the licenses. That will give communities more control over both the quantity and quality of alcohol retailers. It will make the market more accessible for new businesses. It will keep prices lower for customers.

Licenses should be issued and transferred to responsible business owners who fully appreciate concerns regarding excessive drinking and operating under the influence. People are going to drink. It is better if they do so sensibly, and while consuming food.

In the meantime, Chelmsford has plenty of licenses available for off-premise wine and malt licenses. That is because they have chosen not to issue any. This topic came up in 2010 when a new business in town applied for a license. The Board of Selectman denied the application in a 3-2 vote.

The current Board of Selectman is reviewing their policy of not granting alcohol licenses to food stores. As I suggested at the top, their policy should benefit the community, not the liquor oligopoly.

Again, the willingness to grant licenses is an economic development issue. What if an upscale cheese shop was considering Chelmsford Center, or a pre-prepared meals store? A lot of people still remember The Elegant Farmer in Chelmsford Center. Perhaps specialty food stores would thrive in Chelmsford if the town allowed them to sell the right wine to go with the food customers were bringing home. When the customers bring the food and wine home, they are less likely to drive under the influence.

Some businesses will not pursue coming to Chelmsford once they find out the town has a policy of not issuing them a license. Trader Joe’s moved from Tyngsboro to Nashua, not because of taxes, but because of their inability to get a liquor license.

The liquor lobby has been very successful in defeating legislation that would promote competition. They were successful in restoring the exemption from the sales tax. One of their strategies was to claim they were protecting consumers from higher prices.

Restricting supply exposes consumers to higher prices. Restricting supply increases the profits of the liquor oligopoly.

Local governments must be diligent in their protection of community interests. It is in the community’s interest to promote business. It is not in the community’s interest to have strict quota limits that protect a small number of existing businesses. It is not in the community’s interest to limit economic development.

I totally agree with the points you have so clearly made John. The town of Chelmsford can only benefit if it allows the Capitalistic forces of fair & open competition to prevail when issuing future alcoholic beverage licenses…and, as you stated, the licenses should be owned by the cities and towns, not by individual retailers.

Great read – very informative and I completely agree. It is unfortunate and quite surprising that the One Ten Grill lost their license due to the irresponsibility of previous ownership.