Geoffrey Douglas: Loving the Miracle Mets

Geoffrey Douglas is an American author, journalist, and former adjunct professor of writing at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell. His most recent nonfiction book is The Grifter, The Poet, and The Runaway Train (2019), a collection of his stories in Yankee magazine. Other books include The Game of Their Lives (1996, 2005), about the 1950 FIFA World Cup soccer match between the United States and England), which resulted in a movie of the same name (2005) starring Gerard Butler and Wes Bentley, and The Classmates: Privilege, Chaos and the End of an Era (2008).

The ’69 Mets: A Time and Season to Remember

By Geoffrey Douglas

As a school-kid in New York City in the early1950s — the years before the Giants and Dodgers both left town — the purity of your baseball loyalty was measured mostly by the size of your Topps collection. The Yankees’ and Dodgers’ cards were always the most available and easiest to trade for — Mantle and Berra were at their peak then, along with Peewee Reese and Duke Snider in Brooklyn— while the Giants, definitely the city’s caboose team, seemed (with the exception, of course, of Willie Mays) perennially short of stars.

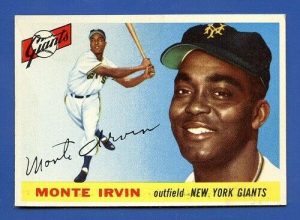

Most of the kids in my class were Yankees fans. I liked the Giants — loved them, really, was passionate about them, and would trade for any Giants card that came on our third-grade homeroom market. (I remember that I once traded several Dodger cards for a single Monte Irvin, a transaction that earned me weeks of scorn from the class’s in-the-know traders.)

I can’t say for sure why I felt such loyalty toward this luckless team — maybe because on my only trip to the Polo Grounds to watch them, in 1952 or ’53, they’d beaten the Dodgers (which rarely happened), and a mid-game foul ball from one of their hitters had landed within a seat or two of me. Of such small moments, in the life of an unsure eight-year old, is devotion built.

But mostly, loving them was a pretty thankless affair. While the Yankees made it to the World Series eight times through the ‘50s, and the Dodgers four times (this was in the day of eight-team leagues), the Giants managed it just once, in 1954 — then followed that with three years of losses. Fan interest waned; thousands of seats went unsold. Then in August 1957, a month after my 13th birthday, came the death knell: the Giants were moving to San Francisco, the Polo Grounds would be razed. I’d gone away to school by then, but had never stopped rooting, or traded away a single Giants card.

For a long time after, I didn’t know what to do with my loyalties. The Dodgers had left the city too (transplanted to LA the same year the Giants left), and I couldn’t bear the thought of rooting for the Yankees, whom I’d hated at least since first grade. For a while I pulled for the Chicago Cubs, who’d signed an all-star outfielder named Bobby Thompson I remembered from his Giants days, but they never even managed a .500 season, so there wasn’t much future in that.

Then in 1962, to huge fanfare, came the Mets. The League’s newest expansion club, they seemed to have been created as a kind of hybrid, a consolation prize to New Yorkers for their double-whammy loss of five years before. With team colors that combined the old Dodgers’ blue with the Giants’ bright orange, a mascot — “Mr. Met” — whose goofy face on an oversize baseball-head made him look like a giant bug on human legs, an inaugural yearbook cover that featured a toddler in baseball cap and diapers; and a 71-year-old manager, Casey Stengel, whose acceptance speech turned on the line, “Most people my age are dead at the present time” — they were an instant sensation all over the League. The fact that they would play at the old Giants’ Polo Grounds, which had been spared the wrecking ball but had been derelict since the end the end of the ’57 season, sealed the deal for New Yorkers. Including this one. I loved them unconditionally from the day they took the field.

Their line-up was a colossal tease. Though relying mostly on a bench of journeymen who’d toiled for years in obscurity (and would remain there), it was headlined by a handful of former all-stars — Gil Hodges, Richie Ashburn, Clem Labiine, all now approaching forty — whose career credentials seemed enough to draw the crowds back, at least for a time, and to offer a measure of hope to those of us so in need of it.

Their first game, a dreary, error-filled 11-4 loss to the Cardinals in St. Louis, would prove a mirror of what was to come. They lost the eight games that followed, to open the season 0-9, then seemed for a while to settle down, then lost 17 straight to bring them to 12-36. They finished the season in last place, 60 games back, with 120 losses (and 210 errors)— you have to go back to 1899 to find a team with more losses.

It got no better. Last place again in ’63, ’64, and ’65, never with fewer than 109 losses. They were awful, atrocious, abysmal, as bad as any team had ever been. But something about them— their gargantuan ineptitude, their record-setting errors, “Marvelous Marv” Throneberry’s comical goofs at first base and on the base paths, the outrageous stuff that came out of Casey Stengel’s mouth — won the fans’ hearts and kept the seats mostly filled. By the end of the ’63 season all of New York had come to love them. The worst professional team in any sport that had ever played for the city (maybe for any city), by the end of ’63 they had earned the title, pretty much officially, that you’d been seeing for months on the T-shirts all over town: “The Lovable Losers.”

Then in ’68, a sliver of progress. They finished that season in ninth place — second to last, with a 73-89 record, their best ever— 24 games back. By the standards of the prior six years, it was more than respectable. It was a triumph. And they had a new manager, Gil Hodges, who actually said intelligible things; and a hot young pitcher named Tom Seaver, who’d won 16 games the year before. Going into the ’69 season, it seemed they might be getting close to contending.

I was 24 by then, a hotshot freelance writer in New York, very sure of the ways of baseball and the world. And I was a lover of underdogs, and of the Mets —and convinced of what I saw coming. I was also, on this particular April evening a week or so before the season opener, three or four bourbons past objective thinking.

“They’re gonna take it all this year,” I said, very knowingly I’m sure, to my cousin Stuart, on the adjoining barstool, somewhere around eight or nine o’clock.

He made a funny noise in his throat that sounded like contempt. “They finished ninth last year,” he said. “Ninth. Ninth out of ten.” That was all he said.

I told him I knew where they’d finished — but the pieces were all in place this year. They were going all the way, they were gonna take it all. I’m not sure if I believed it or not, but you say those sorts of things in bars.

He asked me if I wanted to bet on it. I said he’d have to give me big odds. He offered twenty to one. I said I wanted thirty. We settled on twenty-to-one for the pennant, thirty if they won the Series. The bet was ten dollars —three hundred for me if they went all the way. Which by this stage of things I was thinking they probably wouldn’t. But it was only ten dollars.

We shook on it. “You might as well just pay me now,” he said. I thought he was probably right.

You know the story from there, maybe too well. How they opened the season in standard clunker fashion, then reeled off eleven straight to pull close, then cooled again and were 9 1/2 games back of the Cubs in mid-August — by all accounts out of contention — before ripping through the last eight weeks of the season (“like a blindsiding nighttime tornado,” as one old-time scribe recalls it), winning 38 of their final 49 games to close out with 100 wins and leave Chicago in the dust. Then a 3-0 sweep against Atlanta to take the NL pennant, followed by four out of five against Baltimore in the Series to win it all.

Then the ticker-tape parade, the interviews, the books, the screenplays, the “Amazin’s”, the “Miracle Mets” — the whole six months of hoopla before the next season’s back-to-earth, third-place finish.

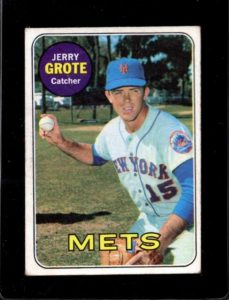

Most of the details of that ’69 season have blurred in my mind all these years later (I just had to check online to confirm whom they’d beaten to take the pennant) — but the memories of the moments stick like glue: Tommie Agee’s four-hit, two-homer late-season game against the Giants (against my Giants!); Seaver’s 10-0 run to close the regular season; the night they struck out 19 times, committed four errors and still somehow beat St. Louis; Nolan Ryan and Jerry Grote rolling on the mound together, pounding each other silly, after the last out of the pennant win against Atlanta; Ron Swoboda’s full-tilt, sprawling catch to save Game 4 of the Series; Tug McGraw’s gritty late-inning relief work; Donn Clendenon’s near-daily heroics. So many more. They play back sometimes spool-like in my mind.

I was on a fishing trip in the Adirondacks the day they closed out the Series against Baltimore in October, though I listened to every out of Curt Gowdy’s radio play-by-play. Three or four days later I saw Stuart in New York. He was chagrined, but gracious; he paid me $100, all he could afford at time time (he was in business school, working part-time, and barely had enough to make rent.); he promised the rest when he could manage it. Two months went by with more promises. By December I was feeling remorseful. And Christmas was coming — so I wrote him a poem, and arranged for him to find it under the tree. It began:

Oh Stu, are you yet a believer

In the arm of Mets pitcher Tom Seaver?

Has the bat of Agee yet caused you to see

That the Mets are a costly deceiver?

It went on a while longer with several more lines of gentle taunting, then closed in the spirit of the season:

But now for your folly you’ve paid;

From your conscience at last may it fade.

As of Christmas this year, Stuart, be of good cheer,

And know that your debt has been paid.

A week or so after Christmas a large, flat package arrived in the mail for me. It was from Stuart — a framed copy of the front page of the October 17th Daily News, Above a photo of Game 5 pitcher Jerry Koosman on the mound in the arms of catcher Jerry Grote, it featured the headline, in two-inch tall bold caps:

METS ARE NO. 1

I kept that picture, first on my wall, then in successive attics, until it literally fell apart several years ago. Stuart tells me he still has the poem. Some memories, sweet or bitter, are just worth holding on to.

****