Remembering Colin J. (Leo) Reilly, Lowell Writer

Writer Stephen O’Connor of Lowell recalls his neighbor in the Highlands and a fellow writer from the city. Since last fall, this blog has become a resource site for information about writers with links to Lowell, emphasizing people who are active now but also adding profiles of writers from the recent past. Note the “Literary Lowell–Plus” button at the top right of the home page. If you have a suggestion for a writer to add to our list, please let us know.- PM

Remembering Colin J. (Leo) Reilly, Lowell Writer

by Stephen O’Connor

I can’t say I knew the late poet Leo Reilly well. A five-year age difference is a considerable one among children or adolescents. But because his front porch was visible from our front porch, I saw him coming and going, and we gave each other a wave or a nod. Later, much later, probably after I returned to Lowell from college in the late ‘70s, I’d see Leo, getting out of an A&L cab, a bit disheveled and a tad unsteady on his feet. I don’t think I even waved at that point, out of fear of embarrassing him.

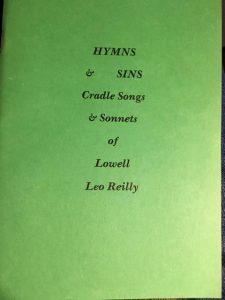

I may have, I’m sure I did, chalk him up as one of the sad souls lost to addiction, someone who didn’t have much going for him and squandered what he did have. Sadly, there were many such cases in those days. That assessment was incorrect, though. Turns out Leo had a lot going for him. He had brains. I wasn’t aware, somehow, that he had earned a degree in biology from UMass and worked for a time as a microbiologist at the Lowell Regional Wastewater Utility. I was also unaware that Leo was a member of MENSA, the high-IQ society formed in 1946. You have to score way up on the scale to make it into that club. The biggest surprise occurred when, somewhere around 1977, I came into possession (I don’t remember how) of a slim green booklet of poetry Leo had published called Hymns & Sins, Cradle Songs and Sonnets of Lowell. Now I’m sure Paul Marion was writing poetry in those days, but I didn’t know Paul. I didn’t know my neighbor Leo, either.

There were not many poets or writers or artists in Lowell in the ’70s. Lowell National Historical Park showed up a year after Leo’s book. Canal tours on boats, Lowell Celebrates Kerouac! literary festivals, Western Ave. Studios, the Lowell Folk Festival—none of these things had come into being though some Lowellians had big dreams. The old cynicism persisted. I recall a guy in a downtown bar proclaiming, “They’re trying to sell Lowell, but they’re not going to sell it to me! I’ve lived in Lowell all my life, and there are more goons in this town than priests in the Vatican!”

The “art” that was “the handmaid of human good” in the city motto referenced artisanal textile workers, the weavers and loom-fixers of our past. And that past, for many, was nothing to be proud of. The same barroom malcontent had declared: “My parents slaved their lives away in those mills. As far as I’m concerned, they’re an eyesore. Tear them down!”

I could understand those sentiments. Leo’s parents and my parents had gone through the Great Depression, the surprise attack on our Navy at Pearl Harbor, and a World War. We can hardly blame them if they were more concerned with survival than with making art. Lowell was gritty; it was working-class. I certainly never imagined the city as a cultural mecca, and I believe that Leo would have shared my pessimism. I’m sure it was for this reason that he sought out kindred spirits in Boston, joining the New Writers Collective and The Fire of Prometheus Poetry Troupe of Cambridge. Leo was popular as a reader, and in 1986 he published another collection, Coming to Consciousness. He attended poetry readings in Allston, where once, Leo and his brother, local musician Kevin Reilly, performed a song they had co-written, “My Shades.” As in sunglasses.

It makes me think, though, of a line out of Joyce, “One by one, they were all becoming shades.” When we are gone, what remains of us in the minds of others, our shade, if you will, are small anecdotes and disjointed facts. Things that say something about a person, and yet are hard to put together. Leo smoked Marlboros. He had a dry wit.

My older brother Rory was a year behind Leo at Keith Academy. He tells me, “Leo was no lily-livered poet. He was a scrapper, like his brother Harpo. We used to cut up behind the Commodore going to or from the school. One day some kid yelled something at him. Leo was ready. He walked up and asked this kid in a deliberate and sort of measured way who the hell he thought he was talking to and told him he was going to kick his ass down the street. The kid took off.” Anecdotes. Or maybe, as Yeats would have said, “Character isolated by a deed.”

Leo lived in the attic of his parents’ home, “the garret,” if you will, like many a poet before him. From the window of that perch, he could survey the neighborhood, and write.

So let us make small talk

About how yr life is at stake.

Surely we can laugh

(after a serious time)

At the tragedy our lives have been.

The stamp of liberating failure

Is in yr smile: how you enjoy

NOW

By talking about the concrete past

The plastic present,

The vaporous future.

We bless each other in laughter

Like two winter travelers who missed the train

But are warm in overcoats

And still can buy a meal.

I think of Leo up there in his room at the top of the house as I think of Jack Kerouac, a sort of Catholic mystic. The words “blessing,” “faith,” “God,” “sacrament” “peace” and “Love,” (always capitalized) recur continually in his poetry. At one point he urges us: “Turn off your TV, and learn to pray.” It is not an orthodox Catholicism, but a longing to touch the divine. Here’s Leo:

The alcohol, the drugs

The rocking music

No longer fill me up.

Charles Jarvis wrote in his biography of the author, Visions of Kerouac, that he once asked Jack why he drank so much, to which he responded, “It’s my liquid suit of armor.” There are some people, and often, I suppose, they are artists, who feel too much. And more from Leo:

pornography, anything imaginable prostituted

blasphemed

the banal violence of everyday life, everywhere,

–kick the dog, beat a woman, child, shoot main

kill, assassinate with the tongue–

Suffering Jesus how can You take it

nailed to the Cross

Glorified Jesus in Heaven how long can you

let this go on

At some point I had read James Joyce’s Dubliners and began to see that though writers were lacking in Lowell, material was not. I had thought that I’d like to write about the people of Lowell, produce something from a Lowell perspective, and here was a guy, a neighbor, writing “songs and sonnets” of Lowell. I believe it was Edna St. Vincent Millay who wrote, “To publish a book is to stand naked before the world.” In Leo’s case, it was his very soul that he bared. He wrote of his failures, of his sex life, of his struggle to find Love and meaning in life. He was the first writer I knew who had the guts to put his heart out there before the world.

Still, I don’t recall that I ever talked to Leo, back then, about his poetry. I saw a bit more of him later on, in the ‘80s, usually as we met walking around the neighborhood. And finally, I did talk to him about poetry. I recall him telling me that he had just bought Allen Ginsberg’s Collected Poems, 1947-1997. I was impressed because I knew that book would cost at least twenty-five dollars, and that Leo probably didn’t have any more money than I did.

My father died in 1987, and a few days after the funeral, Leo rang my mother’s doorbell. He had not been drinking. He was quite sober and had come to express his condolences. Elinor invited him in, and they sat in the kitchen and drank a cup of coffee and talked. I wish I could relate that conversation to you, but all I can tell you is that after that visit, if anyone referred to him as a heavy drinker or a ne’er-do-well, my mother always insisted, “Leo is a good man.” Too soon, that became, “Leo was a good man.” He died in March of 1991 of a heart attack at the age of forty.

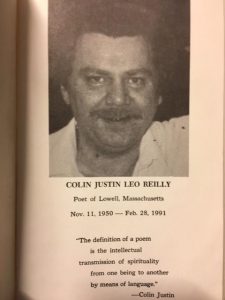

I did attend his wake and met there the writers and poets from Boston who had loved him and held him in high esteem, and who knew him better than I had. They referred to him under the poetic pseudonym he had adopted, Colin Justin, and indeed, the obituary in The Lowell Sun had announced the death of Colin J. Reilly. I was familiar with Leo Reilly, but I realized I had never really known Colin Justin. A third volume of Leo’s poetry, The Poet Beggar’s Sermon, was published posthumously by Leo’s parents.

When Paul Marion asked me to write a brief recollection of Leo for the RichardHowe.com blog, he communicated his thoughts in a way that summed up better than I can what the poet meant to him and others, and where he stands in the literary history of our city:

“There’s a phrase used by Jack Kerouac in one of his books or maybe in a letter. He’s writing about his mother, and he praises her for “the simple attempt” to do the right thing, to do what has to be done. All judgement aside, the chin-stroking pedigreed critics, Mr. Leo of Lowell earned himself some credit for making the effort, trying to compose a few poems for readers beyond his ken. He’s a brick in the Lowell cultural wall. He was doing something on his own at a time when there was not a lot of that going around. He’s on the record, in the records, because of those few slim volumes.”

And when the solid sorrow wall

Of our unspoken discontent

Has fallen, brick by brick,

Beneath our love’s good hand,

Then the touch will thrill a nerve

In soothing, quiet rolling joy,

But being in the ocean’s cold

The rising rush and heat

Will turn the seatide pull to light

Our long-forgotten memories.

—Leo Reilly, Colin Justin, from “Ruth’s Marriage”

Because of your masterful and touching words, Stephen O’Connor, I wish I knew him, too.

Steve,

What a wonderful article you’ve written about Leo!.

I’m sure he’s looking down with a happy wry smile on his face knowing that because of YOU he’ll finally be will acknowledged (and deservedly so) as a “brick in Lowell’s cultural wall”.

THANK YOU for giving me your story about our dear brother Colin to share with my family as a VERY special Christmas gift.

God Bless You!, Peace, Kevin Reilly ;-)

Everything you write is pure gold O’Connor. Beautifully done as always.

Enjoyed this. I’m finding out “there’s a lot to learn about Lowell”

I finally found, “The Poet Beggar’s Sermon” by Leo Reilly . If I remember Leo max. his college boards. He had a brother whom was a Vietnam veteran . His parents were super . Still looking for my ” Hymns & Sins” book.