1969 in Lowell: Raymond Mungo on the River Road

Raymond Mungo is a writer whose books should be more familiar than they are to readers in the Merrimack Valley. He has lived in Southern California for many years, but he was born in Lawrence and graduated from Boston University, where he gained national attention as the politically radical editor of the student newspaper during the tumultuous mid-1960s. I recently posted about Raymond on my personal blog, paulmarion.com, where there’s more about Ray and how I first heard about him in high school, as well as a poem by his longtime friend and collaborator, Verandah Porche, a poet and community activist in Vermont.

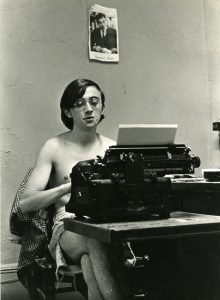

Raymond Mungo, 1967 (web photo courtesy of UMass Amherst Libraries)

Raymond’s two memoirs from 1970 (consider how hot a writer he was to have two books in a year) are the books for which he is best known: “Famous Long Ago: My Life and Times with Liberation News Service” and “Total Loss Farm: A Year in the Life.” I had read “Famous Long Ago,” but knew little about the second book. I’ve written and read a lot about Lowell in the past 40 years, so imagine my surprise when I recently began reading “Total Loss Farm” and saw the first section, “Fall,” subtitled “Another Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers.” Henry David Thoreau was a writer-hero of Ray’s, so it’s no surprise that he and a few friends decided in the fall of 1969 to retrace the boat trip Henry and his brother John took in 1839. “A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers,” much of which was written while Thoreau was encamped at Walden Pond, was published in 1849—interestingly, a do-it-yourself publication because no publisher in Boston or New York would take it on. All these years later, the book is in print and central to Thoreau’s legacy.

For 23-year-old Ray, seeking relief from being on the front lines opposing the war in Vietnam, pushing for Civil Rights, trying to open up the mind of the Establishment in the country—for Ray, the idea of being free and peaceful on the water came to him in a sleep-dream helped along by a certain pharmaceutical that was at hand. He writes, “Yet this canoe trip had to be made because there was adventure out there. We expected to find the Concord and Merrimack rivers polluted but still beautiful, and to witness firsthand the startling juxtaposition of old New England, land and water and mountains, and new America, factories and highways and dams; and to thus educate ourselves further in the works of God and man.” Applying Thoreau’s model, Mungo’s day-to-day accounts track the adventure from Concord, Mass., to Ashland, N.H.

Along the way, the traveling group gets to Lowell and sees more of it than Henry and John did because they skirted the mill district downtown, using the Middlesex Canal through the Highlands neighborhood before putting in to the Merrimack approximately opposite today’s Hadley Field on Middlesex Street, north of the Pawtucket Falls, giving them smooth water on the route to Tyngsborough and New Hampshire.

Of special interest to me is Raymond’s account of the Lowell segment of the trip, “Tuesday: Lowell, Mass.,” and pages preceding that section as the travelers anticipate reaching the city. There isn’t much published writing about Lowell in 1969. Of course, back issues of the Lowell Sun add up to a picture of life in the city at the time, but that’s not the same as reading a memoir. Jack Kerouac’s true-story novels set largely in Lowell portray city life in the 1920s and ‘30s and double as social history even if fiction. After Kerouac’s youth, after World War II, there’s little fiction or nonfiction to give readers a textured sense of Lowell life. Charles Jarvis or Ziavras published a few novels set in mid-twentieth century Lowell. Tracy Winn’s “Mrs. Somebody Somebody” (Random House, 2010) offers short stories set in post-WWII Lowell. David Daniel’s private eye novels such as the prize-winning “The Heaven Stone” (St. Martin’s, 1994) paint rich portraits and landscapes of a more recent Lowell, Jack Dacey has a book about his experiences driving a cab in Lowell, and Steve O’Connor in “Smokestack Lightning” (Loom Press, 2010) uses modern city locations and characters to full effect in vivid stories. Some of the best first-hand accounts of later twentieth-century experiences are in the transcriptions of oral histories at the UMass Lowell Center for Lowell History, a unit of the university library. For his part, Raymond Mungo gives us a brief report on his hours in the city. Even as the gritty details pile up, the reader knows Mungo feels the local hurt as only a downriver cousin from Lawrence might. And he recalls small kindnesses such as this surprise at their boulevard campsite: “Around midnight, a group of married couples arrived with Dunkin Donuts for us to eat; they had heard of the legendary canoe, it was all over town. . . .”

Unlike the Thoreau boys, Mungo and company followed the Concord River through Carlisle and North Billerica on the way to the confluence of Concord and Merrimack near Lowell Memorial Auditorium. It’s common for people to think Thoreau floated by what is now the UMass Lowell Inn and Conference Center, but, as mentioned above, he linked to the Merrimack via the Middlesex Canal beyond the Rourke Bridge. Ray and friends aimed for the heart of the city and pulled their canoe out of the water at dusk, marching with it down Central Street in search of a place to spend the night. Here are Mungo’s impressions:

“There is a strikingly 19th-century downtown area but, despite the energetic promotion of the oldest merchants in town, it is slowly corroding as it loses ground to the highway shopping plazas. Life there is sooty, and even the young people look hard and wrinkled. Though it is only a stone’s throw away from cultured, boring Boston, it may as well be a thousand miles away for all the intellectual influence it has absorbed.”

Ray has a soft spot for Kerouac and knows he came back to Lowell around this time. At one point he says he wants “to go get Kerouac and put him in the middle of the canoe and take him north to New Hampshire” to save him. Speaking in his mind to Jack, he reminds him that Robert Frost and Leonard Bernstein grew up in Lawrence, Ray’s hometown, but both of them “got out!” For the record, Kerouac, his wife, Stella, and Jack’s mother, Gabrielle, had quit the house on Sanders Ave. and hit the road to St. Petersburg, Florida, by the time Ray washed up on the Lowell shore.

I won’t run through the Lowell section in detail so as not to give away all the colorful parts. The voyagers got a lift in a truck driven by a Boston newspaper reporter and then camped on the boulevard beyond Pawtucket Falls close to lovers in their steamy cars watching the submarine races, waking to see the G.E. plant sign shining in the sky. From there they connected with a friend and drove past Nashua and beyond before re-entering the river for the final leg of the Thoreau route.

If you remember the Sixties in America or are a young person who wants to know more about what happened then, especially from the vantage point of people in their early twenties at the time, Raymond Mungo’s books are well worth reading as documents of a time when the country was going through extraordinary changes.