George Chigas on Easter for a Greek Family

Kristos Anestis!

By George Chigas

Kristos Anestis

Alithos Anestis

Christ has risen!

Indeed, He has risen!

Saying that to people as they arrived at the house was about as religious as it got for our family at Easter. I think Aunt Filitsa was the only one who really made it a point of going to church. The men of course have a built in excuse. We have to start the fire for the lamb. But it’s true. The women in the family are much holier than the men. And that’s a good thing. It compensates for our disproportionate evil. Thanks to the women in the family we can still look God in the eye and be reasonably sure he won’t strike us dead, even if we do deserve it. And the men are needed to start the fire for the lamb, which is why God always waits until after Easter to strike us dead.

Starting the Easter fire is not something you do well the first try. It takes years of practice to learn the finer points of starting and more importantly tending the fire as it’s cooking the lamb. It’s a knowledge that’s passed down from father to son over generations. It’s like fishing or certain odd mannerisms like grinding one’s teeth that become a family trait and get printed on your forehead as if to say, “I’m Bill’s son.” It’s like the suffix at the end of English names: Richardson or Robertson, for example. If fact in Greek “- opulous” means “son of” if I’m not mistaken. So, for example, “Eliopulous” means “son of Eli.” But I may be wrong. You see my generation didn’t learn a lot of the language. We went to Greek school when we were young, but that was pretty much useless.

A few years ago I felt guilty that I couldn’t speak the tongue of our ancestors, so I bought some Greek language tapes and played them in the car on the way to work. I learned a couple sentences like, “Ti hora fevgi sto layoforio” which means if I remember correctly, “What time is the resurrection?”

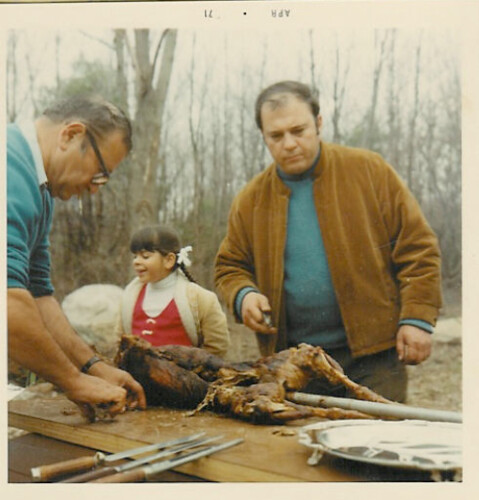

But yes, the fire that cooks the spring lamb is crucial, almost as important as the lamb itself. And attaching the lamb to the spit is perhaps the most important ritual of the Easter holiday. It’s done the night before in the kitchen with wire and pliers. It takes two people, two men, to pull the wires tight enough to secure the lamb so it won’t come loose. It’s definitely a man’s job like starting the fire. (That makes two reasons God has to keep us around until at least after Easter: to start the fire and fasten the lamb to the spit.) And now that I think of it, the whole process of laying out the lamb and tying its legs and body to the steel spit is very much like a crucifixion. On Easter, we men, the sons of our fathers, crucify the son of God, our Father who art in Heaven. It’s kind of creepy. But that’s not at all what we’re thinking when we do it. I’d say what the men are thinking (and maybe the women too) when we crucify our savior is a bit more secular you might say. Especially as the night wears on and everyone’s had two or three drinks. When the time comes to shove the spit up the backside of the lamb and pierce its skull (I’m sorry there’s no other way to say this), it’s the Greek shepherd jokes that come to mind more than anything else. Hey, did you hear the one about the Greek and Italian shepherds? (Perhaps we’d better save that one for another time.)

But it should be duly noted that the procedure of fastening the lamb to the spit is taken very seriously, like a life and death operation. And that’s just how my father and Bill (his cousin) approached it, as surgeons. Bill in fact is an orthopedic surgeon and my father (before he retired) was a dentist like Bill’s father, my father’s uncle, was; and my father’s father was a doctor. (I say this to underline the idea of skills passed down from father to son over generations.) So when my father (whose name is Bill too) and Bill (my father’s cousin) performed this vital operation, the kitchen was magically transformed in into an OR and the kitchen counter where the lamb was laid out an operating table. The two doctors were the servants of God who performed His will to resurrect the patient, His son, the very dead lamb, who’s been in the basement freezer since Good Friday when I picked Him up from the Demoulas market.

The whole task of ordering the lamb from DeMoulas’s is another story that warrants I think another short digression. (After all isn’t the business of telling a story is a digression in itself? There’s no straight shot from beginning to end, it’s all a meandering meditation of mind and meaning.) Anyway… it’s illegal I think to buy a lamb with the head still attached. But for Easter it’s critical to have the head. First of all, it wouldn’t look right if it were just the body turning around over the fire without the head. It would be sacrilegious; something the French might do, but not a God-fearing Greek. No, the lamb must definitely have its head or it isn’t really Easter. You might as well call it “a cookout” or a Bar Mitzvah. But as I say, it’s illegal. The SPCA or someone made it their cause to undermine the very foundations of Greek culture and paid off the governor to pass it into law. Some people in the family think it might have been a Jewish conspiracy. And that theory has yet to be convincingly disproved. But not to worry Mike Demoulas saw to it that all the Greeks in the Lowell area could get a lamb with a head for Easter as God intended.

To do this you simply have to go to the Demoulas market meat department about two weeks in advance and put in an order. But it has to be done discreetly. You don’t just walk up to Dimitri at the meat counter and announce for all the world to hear, “Dimitri, reserve me a lamb for Easter. And don’t forget the head.” You never know, an agent from the SPCA might be recording the whole thing. No, you have to be discrete, almost secretive like a spy. You have to go up to the meat counter and catch Dimitri’s eye. And when he sees you and recognizes who you are by the name printed on your forehead that says, “I’m Bill’s son” which only Greek butchers can see- (It’s completely invisible to the Irish and even the Italian butchers, but the Greek butchers can see it as clear as the nose on your face, especially Dimitri who has such extraordinary vision he can see three generations back. So when Dimitri looks, he sees: “Son of Bill, son of George, son of John, etc., etc.,” just like a verse from Genesis. So when Dimitri gives you the nod, you go to meet him at the swinging doors that lead to the back room and you shake hands and say, “Hi,” like you were just talking about the weather or the dog races or something, and then you kind of lower your head and talk under your breath in Greek. It has to be in Greek as another layer of precaution, so even if the SPCA has somehow bugged the conversation, they won’t be able to understand. And Dimitri takes your order, and a few days before Easter Sunday you come back. When no one is looking he passes you the lamb wrapped up in cheesecloth inside brown paper, and you put it in your shopping cart where it kind of slumps against the side. It’s best to go with two or three other people who can walk beside the carriage, so other people can’t see that you’re pushing the dead body of Christ wrapped in a cheesecloth shroud to the checkout counter.

When I get home I put the lamb in the freezer in the basement, where there’s also bags of ice that we’ve been filling for weeks from the ice maker that Papou found somewhere and fixed-up somehow. And on the night before Easter I go down to the freezer and lift the stiff body over my shoulder and carry it up the stairs like Mt. Canaan and lay it down on the kitchen counter to be “nailed to the cross.” And, like I said, my father and Bill, both of the medical profession, take this quite seriously. They have all their instruments laid out on a white cloth: two pairs of sturdy pliers for pulling the wires tight; two pairs of needle nose pliers for suturing up the stomach after the procedure is finished; two sharp knives for making slits for the garlic cloves; and a spool of heavy gauge wire. Then to the side there’s a bowl of sliced lemons; and a bowl of lemon juice mixed with pepper for rubbing down the inside of the abdominal cavity; and another bowl full of peeled garlic cloves for inserting into the slits they make in the shoulders and legs. When all of the instruments are materials are neatly laid out, they scrub up and put on latex gloves and bend down to their task. My brother and I and our cousin, William, the sons of Bill and Bill, stand to the side watching carefully, trying to remember each step of the procedure, each movement of the hand, the timing of each sip of ouzo. We assist when called upon to do so; otherwise, we stand to the side in respectful silence like good altar boys. During the procedure the two Bills talk to each other using a medical terminology that only they can fully comprehend:

Bill (my father’s cousin): Bill, I’m making an incision along the River Styx just above the marsupial lip.

Bill (my father, cautions him): Slowly now. Beware of temptation.

Bill (his cousin): Right… a little more…. OK… perfect. George (he calls me) give me some light here please. (And I quickly grab the large six battery flashlight and shine it on the patient.) Hmmm… just as I thought. See that!?

Bill (my father): Yeah… looks like melanoma of the redemption.

Bill (his cousin): Right. The sins of man did him in. We’ll have to perform a endoectomyocaridoscopy to determine the extent of metastasis of our sins this year.

It’s vital that they remove all our sins or risk eternal damnation for the entire family. Depending on the extent of our sins for that particular year, the operation can take up to two hours including short breaks for more ouzo.

Fortunately, the virtues of the women compensate for our vices and the size of the tumor is usually manageable. During the ouzo breaks my brother Charles and cousin William and I are told to rub down the patient with lemon juice and garlic, and we jump to it like the pit crew of a professional racing team. When the operation is almost finished and before suturing up the stomach, Bill places three or four lemon halves inside the lamb’s stomach. The next day as it’s turning over the fire, the lemon rinds bounce against the stomach wall like against the head of a drum, like its heart trying to come back to life, de-dump…. de-dump…. de-dump…. his tongue hanging out, sweet brown skin peeling off his back.

The fire has to be started early in the morning. While everyone is still sleeping off the beer and wine and ouzo from the night before, my father gets up, puts on his work pants and Greek sailor’s hat and goes out into the chilly gray dawn. Everything’s already set up. There’s a stack of wood to start the fire and bags of charcoal to keep it burning slow and hot throughout the day. We’ve got plenty of wood around because we burn wood for heat during the winter, and today is either the first or last Sunday in April. Easter goes in a four-week cycle. There’s actually a very specific formula for determining which day: the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox. It seems simple enough, but to be sure we refer to the Greek calendar hanging inside the kitchen cabinet at Papou’s house. He hangs a new calendar there every year. One of Papou’s hobbies is keeping track of time. Every Easter he saves one of the dyed red eggs we use after dinner to crack with the person sitting next to you until there’s only one uncracked egg left and that person will have a lucky year- and he keeps it in his refrigerator. So if you opened Papou’s refrigerator door you’d see the red eggs lined up in the egg tray with the date written in black magic marker: 80, 81, 82, up to the present year. For sure, Papou knew time. (Maybe that’s why they call those big hallway clocks grandfather clocks.)

And Papou could fix anything. If something were broken, Granny (we didn’t call her “Yiayia,” we called her Granny)- Granny would say, “Give it to Papou. Papou fix.” Perhaps his greatest achievement was building the family’s first electric spit to replace the old hand crank one brought over from the old country. We used the hand crank version until the year after we moved from Lowell to Chelmsford in 1969.

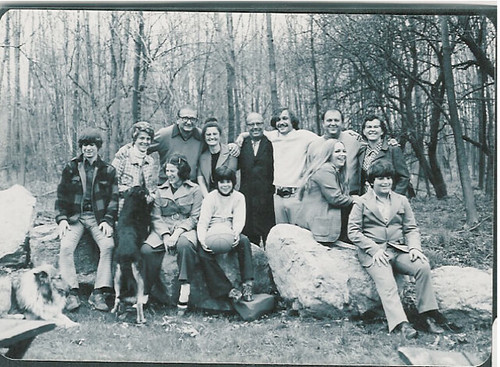

That year, since our house wasn’t finished yet, we held Easter at Uncle Vess’ and Aunt Filitisa’s house on Bartlett Street. In the family picture from that year all the kids are wearing bell bottom pants and have long hair and everyone is lined up along the length of the old wooden trellis that A.G. Pollard had built when he built the house and which years later gradually rotted and buckled slowly under its own weight.

But after that year we used the electric spit that Papou made from the motor of an old refrigerator. He fitted the motor inside a chest of drawers salvaged from the junk yard and rigged it with weights screwed to the metal propeller of an old cooling fan, so you could adjust the ballast to make the spit turn evenly. His invention was unveiled the year we moved into our new house. Papou attached a long extension cord from the house to his invention. Everyone stood around like they must have done when Thomas Edison first demonstrated the first phonograph or telegraph or electric light bulb. We were all filled with tense anticipation wondering if Papou’s new contraption was really going to work. And when he connected the extension cord to the electric motor and the lamb started to turn around by itself, for about ten seconds everyone was speechless. Then we cheered in unison , “Hooray! It works!” It was wonderful. No more turning the lamb by hand. Papou had liberated us from slavery. He was like Moses leading the Jews out of Egypt. Papou had ushered in a new era. It was the immigrant spirit and New England ingenuity all wrapped up into one. “God bless America!” we thought smiling to ourselves.

We’ve been in our new house for about three years now. It’s just starting to look settled. It was built in the middle of ten acres of woods, so we spent every day of the first summer clearing out the trees and brush around the house to make a lawn. We dragged the branches and made huge piles that my father set on fire. It was so hot it singed your eyebrows from fifty yards away. It was drudgery for my brother and I. But my father knew that in the long run, we’d thank him for teaching us the meaning of WORK.

The second summer, my father planted the grass and built a beautiful big brick patio off the back of the house. My brother and I had the job of filling the concrete mixer with sand and carting the bricks from the pallets over to where our father was building the patio walls. “C’mon!” he’d called to us. “More bricks!” And my brother and I would race back and forth with the wheel barrow until it was time to break for lunch and we’d slip away to the tennis and swimming club to meet our friends. But Easter was like a deadline for our family. All the spring projects had to get done in time for Easter. It was like judgment day. If the projects weren’t finished by then… Actually there were no “if”s. The projects had to get done by Easter. Period.

It’s finally Easter morning and my father’s up and it’s drizzling outside and he’s wearing his Greek fisherman’s cap and a maroon Chelmsford High School wind breaker, and he’s pushing a wheel barrow stacked with wood to the fire. He started the fire about an hour ago and even though he’s got enough wood and bags of charcoal to cook three lambs, he wants to be sure there’s enough wood so he won’t have to use the charcoal too soon. Tending the fire is tricky business, and nobody is ever satisfied with how hot on not hot it is. In fact, it’s a running joke that the first thing that Uncle Vess will say when he arrives (after my father hands him a mug of hot coffee) is: “That fire’s not hot enough. At that rate the lamb won’t be ready until five.” And they’ll have a short debate about how hot the fire is, and to appease his older brother who’s been like a father, brother and best friend to him, my father will rake the coals into a pile and add some more wood. But it’s still early and no one has arrived yet, and my brother and I are just waking up and getting something to eat in the kitchen, and out the window we can see our father and Uncle Vess standing at the edge of the lawn talking and smiling and drinking their coffee. Uncle Vess will hang around for a couple of hours while Aunt Filitsa and their two daughters, my first cousins, are at church, then he’ll leave before other people start to arrive and go home to change his clothes then come back with the family, and in the early years my cousins Diana and Daphne would be wearing the same outfit that Aunt Filitsa had sewn for them with her own hands.

Over the years Easter’s been pretty well documented. My mother was the first to commemorate the event with personalized photo albums with made-up conversations beneath the pictures. In the 1969 album for instance, there’s a picture of seven-year-old Daphne sitting on the swing next to Dr. Shore, and beneath the picture the caption that reads: “Dr. Shore, what’s a generation gap anyway?” “Beats me, Daphne. But whatever it is, I hope it’s not contagious!”

Cousin Basil was the first to record the day on video. That was before the days of palm-sized camcorders. So it was a little intimidating to see him appear with his suitcase-size camera perched on his shoulder and the lens sticking its nose in your face. To his credit, Basil would try to break the ice by asking you a disarming question. He catches Bill coming down the patio steps. “Hey Bill!” he calls out from behind his camera, and Bill stops. The video is recording him in black and white in a way that will look surreal when we watch it on TV later as he stands in front of the camera with a drink in his hand, looking a little annoyed at having to make this stop on his way to the dessert table. Basil asks, “What’s the matter, Bill, you look pale. What’s the matter?” And Bill, who’s good at thinking on his feet, answers, “What’s the matter? There’s too many non-Greeks here, that’s what! Who invited all these barbarians?” At that moment my father appears, and Basil pans the camera to frame his flushed face in the lens and asks, “Uncle Bill! How about you! What do you have to say to future generations?” And my father who’s been up since dawn and drinking ouzo since noon replies, “Me? Say?” And Basil tries to help him along. “Let’s start with your name. What’s your name?” And my father replies, “Me? My name? What’s my name?” Basil tries another line of questioning and asks, “What day is it?” Still recovering from the previous questions my father says, “Day? What day is it?” And Bill who’s still standing next to him lets out a hardy laugh and throws his arm around my father his first cousin and says, “C’mon Chigas, let’s get you a drink.”

But the main and central event of the day- besides of course removing the lamb from the fire after it’s cooked- is the family picture on the big rock. After everyone’s finished eating but before people start to go home, my father now many sheets to the wind sets up his 35 mm camera on its tripod in front of the big rock and calls everyone to gather there. But it’s not easy to get everyone moving in the same direction at the same time. Usually, he has to tell everyone two or three times before they stop nibbling on leftovers or baklava and move in the designated direction. He starts to get a little impatient. He calls me, the first born, “George! Would you please help me get people on deck for the f-a-m-i-l-yp- i-c-t-u-r-e.” And I turn to the person next to me and call out, “All hands on deck!” and soon the word gets passed around and the momentum gradually shifts enough so people do start moving toward the big rock to take their places for the family picture.

I can’t help thinking that the rock is like an anchor. It keeps us rooted to each other. To this place and day. Or maybe it’s like the capsized hull of a boat that we cling to. It has that shape. It’s gray like a whale breaking the surface of the water. Rounded. Smooth. And we stand on its back perfectly balanced as the whale breaks through the new green lawn and freezes there like a statue. The whale stops in mid-plunge for everyone to take their places. And the tree beside it is like a fountain of water it blows out its spout. “There she blows!” my father shouts standing behind the camera. He quickly sets the timer and presses the shutter and runs to take his place on the rock next to the tree before the shutter releases. And “snap” the day is recorded for posterity.

History will know who was there for Easter that year. History will know how many socks William was wearing. You see him sitting in the front row. One year he’s got one sock on his left foot and no sock on the right. The next year it’s reversed; the next no socks at all. He’s smiling deviantly. He wonders if History will notice his ankles. He’s planned this out far in advance. When he heard my father call for everyone to take their places, he slipped into the bathroom and took off one of his socks and stuffed it into his pocket. As the picture is being taken, he crouches in the front row with his bare ankle exposed. He can barely keep from laughing as he holds the pocketed sock in his pocketed fist. Thanks to William, when we think back over the years and try to distinguish one Easter from the next, we have this reference. “Oh yeah, that was the year William wore one sock on his left foot. What a year! Perfect weather. Remember how calm the sea was that day?” Or, “Do you remember the year of no socks? What a day that was! The wind was vicious! It nearly blew down the blue tent and sent us all adrift!”

Other family members assume less distinctive poses for the family picture. Uncle Arthur, the tallest, a former star quarterback for Lowell High School then Yale, is looking far off into the distance. He sees someone open in the end zone and throws the game winning pass. Uncle Dino is grinning ear to ear. He knows he’ll live the longest and retire the youngest. He drives a shiny Lincoln down to Florida to wait out the winter. This year I’m Jack Kerouac. I’m wearing a red flannel shirt and baggy pants. Charles, my brother, is wearing a red cashmere v-neck sweater and Brooks Brothers underwear. Basil is holding his new born son in his arms. Daphne has a beer in her hand. We’re all holding onto the hull of the same capsized boat that brought our parents and grandparents from the old country across the deep blue sea teaming with whales surging forward. And even though the hull of its back is kind of slippery and it’s hard to keep our balance, we manage to stand still just long enough for the shutter to open and wink shut. You’d never know that we were all hanging on for dear life. You’d think it was clear sailing. You’d think we were all just skipping over the ocean like a stone.

Nice ethnographic Easter memoir!

Efharisto, George! Your Thea, Mrs. Dakos, was a Yaya to me.

I lovingly remember the Koufogazos Family and the Palantzas Family – we all lived at the top of the hill on Mt. Washington Street. It was there I learned and savored your tradition……head and all! Plus ouzo………

Great! When you say “Mrs Dakos was a Yaya” to you, do mean you were related in some way (through marriage perhaps?)?

I loved reading it, George!! It was moving, amusing and telling!