“Savannah and Lowell: Common Assets and Challenges” by Fred Faust

Fred Faust recently visited Savannah, Georgia, and compared historic preservation efforts in light of ongoing discussions occurring in Lowell about balancing preservation and business needs. Here are his observations:

Savannah Riverfront

Despite climate and geography, Savannah, Georgia, and Lowell, Massachusetts, share a lot in common. Both cities’ early industries were dependent upon cotton. Savannah’s port stored and shipped the raw product, while Lowell’s mills spun the cotton into textiles.

Today, Savannah’s once gritty riverfront warehouses feature 20 or more restaurants, gift shops and brand name hotels. Together with an amazing collection of pre-Civil War residences within four historic districts, this incredible walking city attracts some 12 million visitors annually.

Factors Walk

The success of both cities has from time to time caused tension between those who want to preserve a special core identity with business interests advocating more relaxed rules. here Lowell has recently heard arguments about overregulation of sign boards and flower boxes, Savannah’s Historic Commission is in discussions with developers proposing $100 million-plus projects.

History as an Attraction and Economic Engine

Where Lowell has seen $1 billion invested in recycled buildings over 30 years, Savannah is undergoing a boom that includes a single $300 million hotel and re-use project proposed by Georgia-based Ambling Companies. Centered on a now vacant Georgia Power Company plant, the model pictured below with Savannah Historic Commission Chair Tom Thomson shows a large mixed-use development. It will literally expand riverfront development an additional 54 acres. A cooperative and award-winning master plan was actually crafted back in 2006. Planning and partnerships remain keys but matching standards and plans has been a lengthy process.

Historic Commission Executive Director Tom Thomson

Historic Commission Executive Director Tom Thomson is a certified planner and civil engineer who is responsible for a multi-disciplinary staff of professionals. Thomson mixes experience, passion and humor as he reviews nine years of history in Savanah. Importantly, his agency’s authorities also include wider duties. He also serves as Director of the Metropolitan Planning Commission, which handles regional planning, preservation, transportation, water resources and GIS services.

Savannah was founded in 1733 based on a comprehensive design initiated with remarkable foresight by British General James Oglethorpe. It was the last colonial capital laid out under British direction. Some 21 urban squares, small parks, were created within a grid pattern now adjoined by restored mansions, homes, elevated townhouses, commercial and institutional structures. Live oaks, Spanish moss and statuary within these squares give the downtown unique appeal and livability. Additionally, the once gritty river district beyond Oglethorpe’s bluff takes advantage of the broad Savannah River with its enhanced river walk, ferry connections, and its popular restaurant and entertainment district.

Photo courtesy of Historic Savannah Carriage Tours

Forsyth Park

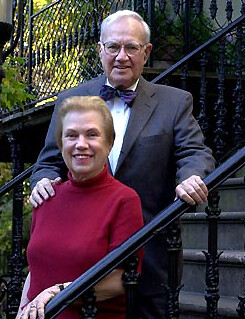

Yet Savannah, like Lowell, was seen as out of date, decrepit and was subject to widespread demolition plans advocated by then-city leaders. It took a core group of women, known as “the seven ladies,” to organize, educate and actually start the purchase of older residences, preserving what is now the most intact national register historic district in America, some 2 ½ square miles in the heart of Savannah. The Historic Savannah Foundation was created as early as 1955. The “ladies” and local advocates, including Lee Adler and his wife Emma, used revolving funds, resold homes with preservation restrictions, and educated the public as to the relationship and quality of historic assets. Adler also tirelessly fought for extending renovation plans to Savannah’s African American neighborhoods, an effort which saw over 500 residences preserved, many as affordable housing. He received the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s highest award as well as the National Medal of the Arts from then-President Bush in 1989. Adler passed away at 89 years of age in 2012, survived by his wife and other family members.

Emma and Lee Adler

As Director of Lowell’s Historic Preservation Commission, I had the opportunity to visit Savannah with our members in 1981. We were hosted by the Adlers, impressed by their energy and dedication, and inspired by the potential their lesson had for Lowell. Returning to Savannah today, I saw that their foresight was even more obvious.

New Retail

Downtown retail

Many in Lowell would be envious of the recent influx of retail shops now appearing on Savannah’s main shopping way, Broughton Street. Back in the 1980’s the street featured nail salons, second-hand stores and discount retailers. Today, the “Hostess City” has upscale retailers such as The Gap, Abercrombie, The Loft, and boutiques like Donna Karan as well as its own local fare such as the Savannah Bee Company and the hard to resist Leopold’s Ice Cream. A major contributor to the downtown is the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD). Developing several in-town campuses, SCAD has helped to add a younger, creative set of downtown residents who support cutting-edge businesses and bring additional energy to the stately downtown. The potential is encouraging for Lowell, were we are witnessing similar trends given the roles now being played by the UMass Lowell and Middlesex Community College expansions. In Savannah, eclectic restaurants and midnight ghost tours play on the city’s other history, which was subject of the 1994 best-seller, “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil,” a seamy tale about a local murder and strange cast of local characters.

Waterfront restaurants

Working with Historic Regulations

Historic Commission Executive Director Thomson, reflecting at his downtown offices with three key staff persons, observed that occasional conflicts are familiar to Savannah as well. He described various ways to minimize issues when working with district owners. He then called on Ellen Harris, Director of Urban Planning and Historic Preservation at the Commission, for specific examples.

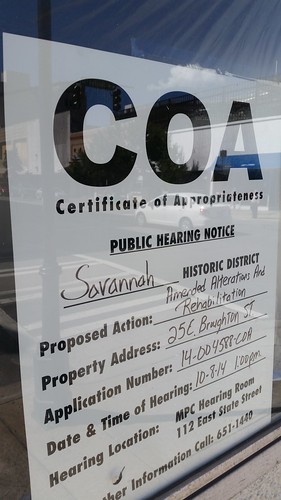

COA Window Permit

“First, we use education and being proactive to inform potential applicants,” says Ellen Harris, chief planner and architect. “We have fliers and on-line tools to let people know what it means to be in a historic district.”

Thomson says in administering design and materials use, they often point to their enabling ordinance and the will of the City Council. “We explain to applicants that we just administer the districts and ordinance,” he explains, “we didn’t just make this up.”

Harris also says they use common sense. Again, this includes education. “Being able to explain why we use certain materials and not others (roofs and windows are frequent issues) is important. And Thomson says that courtesy goes a long way. (After all, this is the South.)

Thomson also comments that the fact that Savannah has many qualified local architectural firms that “get it” and appreciate clear standards, can also help greatly in the process in drawing up plans and working with clients. He says that this is especially true for larger developments.

This leads to a suggestion that the Lowell Historic Board, with the help of the City and National Park, might organize regular technical workshops and seek assistance as well from architectural firms in the area that profit from their associations with Lowell.

Big Versus Little

Waterfront and power plant

The big issues Thomson refers to are larger projects concentrated around the draw of the Savannah River and with a developer who recently purchased an entire main block of Broughton Street. Where the downtown is largely based on restoration or rehabilitation, the expansion of the old warehouse district along the river has attracted major developers who frequently have the firepower and resources to win political support. An rules for new construction elements can be more controversial.

In the past, developers challenged local height restrictions meant to protect the character of the downtown and to avoid massive structures that obstruct or begin to shadow historic properties and the river itself. A compromise in this case was eventually worked out which included additional height but also a bonus system to incent developers to add other features benefitting the public–street improvements or special design features. A controversial intrusion built in 1981, the Hyatt Hotel, spanned River Street and broke the line of historic warehouses, narrowing the river walk and projecting a drab stucco façade practically to the river.

Savannah Hyatt

“When we have a disagreement, it’s not a personal thing,” says Executive Director Thomson. “We mention our mission, the ordinance and our authorities, and we try very hard to work on solutions.” He says it is fairly rare, but that when big developments are at stake that have strong Council and Chamber of Commerce support, a compromise needs to be considered. “When you see the bus coming,” Thomson says, “it’s sometimes a moment to step to the side and not get run over. At that point we try to focus on solutions.”

With Thomson’s skills, staff and other agency authorities; the Commission has a good deal of capital in making the case for preservation. Additionally, with millions of visitors and an economy based on the integrity of an amazing collection of coherent older properties, no one is advocating against historic preservation as a theme for the future.

Impacts of Crime

Savannah TV news

When traveling to Savannah I expected a focus on preservation, tourism and building up economies hard hit by the prior recession. Like Lowell, however, crime is now a major issue is in this community of 143,000. The Savannah Morning News featured three articles on crime the day I left the city last week. One reported a possible gang shooting involving teens, a second an earlier incident, and a third column noted a community proposal for a volunteer “red, white and blue” coalition to provide everything from neighborhood watch to beefed us tourism services. The columnist lamented that many downtown residents no longer felt secure walking the streets. Interestingly, the City Council in Savannah has also recently voted to purchase the same “Shot Spotter” equipment that the Lowell City Council is pursuing after the shooting recently in the area immediate to Lowell City Hall.

Articles and comments by Thomson reinforced concerns about racial inequalities and poor educational opportunities in Greater Savannah. This has led to under-employment and gang activities. A majority of Savannah residents are African American. Interestingly, another one of the Metropolitan Planning Commission’s jobs is to help redistrict the City Council’s voting districts to assure equal representation. This is a task required every ten years in Georgia. As a local columnist pointed out recently, “Try getting nine elected officials to agree on something, while contending with politics, race and federal law.”

Savannah has a City Manager form of government, with an elected mayor chairing the Council. Edna B. Jackson was elected Mayor in 2011. The first African-American woman mayor in the city’s history, her resume summarizes a background in civil rights work and activism. Mayor Jackson and the City Council’s priorities mention job growth, economic opportunities and safe neighborhoods.

What Lowell Can Learn from Savannah

Pawtucket Canal and Lower Locks in Lowell. Photo courtesy Higgins and Ross.

Savannah had 525 applications to their historic board in the past year for work proposed to historic properties. Growth is accelerating and major projects are on the drawing board. A resulting impression is that to be collaborative and successful, Lowell has to scale up.

What does scale up mean? Here are some ideas for further conversation:

- Bolster staff and better integrate Historic Board and Department of Planning and Development staff. Develop an internship program by recruiting UML and MCC students.

- Initiate proactive technical assistance and workshops with assistance from the National Park Service and area architects with Lowell and historic preservation experience.

- Seek special incentive grant and low-interest loan opportunities for historic district properties, adding positive resources to the Historic Board’s menu.

- Focus comprehensive planning actions proactively on larger development, where parties are more likely to agree through dialogue.

- Don’t sweat the smaller issues. Cooperative guidelines should be developed for non-permanent building items that promote and improve appearance such as sign boards, flower boxes and tasteful promotional signs. Involving merchants and community organizations in this dialogue from the start will resolve larger issues.

- Reach out in a positive manner with publications, events and accessible meeting times and locations to better involve the public in regulations, guidelines and review procedures.

- Proactive planning can help to define future development. The Lowell Plan and the City’s recent Master Plan are good starts. These efforts need to be continuous, collaborative and the recommended projects financeable. River and canal sites where university, college, tourism, hospitality, culture and preservation opportunities exist should have the highest priorities. (The Hamilton Canal District is critical, but it should not monopolize resources and public dollars.)

Traveling to Savannah to compare experiences provided for an informed discussion and many insights. Sometimes we need to get away from familiar places and arguments to gain prospective. Returning to Lowell, it appears that our community needs to reaffirm some core values that have helped us to succeed in the past. To continue the successful strong partnerships, to consistently enforce standards related to true preservation issues, and to recognize emerging strengths such as expanding higher education institutions and new entrepreneurs who provide additional opportunities for the future.

Experience has taught us that we are always more productive at that point in time when we can lower our voices, coalesce around common goals, and work together towards a positive outcome. Despite challenges, Lowell and Savannah have rich histories, strong leadership and the type of resources that will enable them to continue to be examples of urban success both now and in the future.

Thank you, Fred for this excellent report, analysis and suggestions for Lowell.

Great series of observations and suggestions for next steps!

Thank you Fred (and Dick) for this thoughtful and detailed analysis. My wife and I visited Savannah eight to ten years ago. It is a lovely very walkable city. While Lowell may never be as much of a destination city, I also think that we may still benefit from Savannah’s example. I agree with your idea that development efforts should probably give the highest priority to “river and canal sites where university, college, tourism, hospitality, culture and preservation opportunities exist,” and I think that this should perhaps extend to the city’s marketing efforts as well. I give tours of the Whistler House Museum of Art once a week, and our guests include many from outside the area – including many from other countries. People from these latter two groups are generally very impressed with the preserved buildings as well as the rivers, canals, and National Park tours. However, they are usually amazed with the quality of art at the WHMA, and throughout the city – as well as the city’s other fine museums. Even people from the general area are surprised to learn that the Lowell Art Association is the oldest incorporated art association in the country, and that we currently have around 300 working artist studios in the city. We could learn from Savannah, and focus on what makes us special.

Savannah is truly a walkable city. I actually stayed at the Hyatt 7-8 years ago. I remember a lot of new construction all over town. They really take advantage of the river waterfront.

Why is UML planning to build a practice rink **behind** the Tsongas arena? This is arguably the nicest stretch of land along the riverwalk and every time I’m down there gets the most use. Doesn’t UML host outdoor events there like charity walks and concerts? I don’t think the public is aware of this.

You could fit a practice rink AND hotel next to the arena. UML’s expansion has been incredible and positive for the city but what’s good for UML might not always be what’s best for the city.