Patrick Kavanagh: a Reader’s Experience

Patrick Kavanagh: a Reader’s Experience

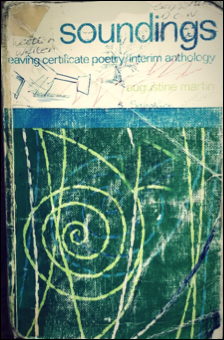

For generations of Irish readers—for this one certainly—the poetry of Patrick Kavanagh is inextricably associated with Soundings, the anthology of prescribed poetry for the Leaving Certificate English curriculum that was a staple of Irish secondary education from the end of the 1960s until the mid-1990s. Edited with sensitivity and skill by the late Augustine (“Gus”) Martin, then professor of English at University College Dublin, Soundings presented the poetry curriculum for the final exam with unashamed emphasis on the texts of the poems, without recourse to illustrations or photographs or that patronising commentary that seems to dominate text books now. Martin in his introduction to the book speaks of “the reflection, frustration and effort” that is a necessary part of learning about poetry; at the same time, he places great emphasis on that poetry as a source of pleasure: “unless delight is behind the learning and teaching of poetry,” he is keen to stress, “the entire exercise is in vain.” The anthology treated pupils seriously as readers and thinkers and the selection of poems met adolescent readers half-way but no further—the selection was inviting, accessible, but still challenging and stimulating. It is no exaggeration to say, for its influence on students and, importantly, on teachers and teaching, Soundings is a landmark in Irish culture of the second half of the twentieth century.

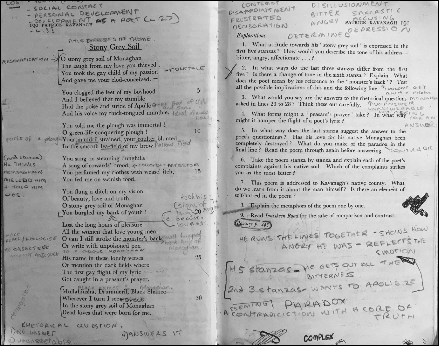

The Patrick Kavanagh selection—six poems—is representative of the man’s peculiar, patchy genius, his “violent energy” as John McGahern would have it, and illustrates well the tactics at play in Martin’s book. The poems by Kavanagh in Soundings continue to live in the minds of those who “did” him. (The examination required us to answer questions on one selected Irish poet from a short-list. It was never clear who would “come up” as there was never a strict rotation. However, Yeats and Kavanagh were safe bets, as one or other was guaranteed to appear, hence Kavanagh has been encountered by most Irish people who graduated high school between 1969 and 1995.) The Kavanagh selection comes from across the poet’s career: “Inniskeen Road: July evening” is from his first book and dates from the late 1930s; “Advent”, “Stony Grey Soil”, and “Memory of my Father” appear in his book A Soul for Sale (1947); and “Canal Bank Walk” and “Lines written on a Seat on the Grand Canal, Dublin” are from Come Dance with Kitty Stobling, published in 1960. The poems speak to adolescent frustration, spiritual longing, and the desire for adulthood in a form that is accessible, nuanced, and hard to forget.

Deliberately out of chronological sequence, “Stony Grey Soil” is presented first by Martin. For a young, male reader in the 1980s (in this writer’s case), the poem’s declaration in its easy, lilting form that somehow Monaghan had “burgled my bank of youth” rang true. Along with Dylan Thomas’s “Fern Hill” (also on the course), “Stony Grey Soil” endorsed one’s frustrations at rural family life (even if one did not share Kavanagh’s farming background) and identified a position from which one could legitimately critique that life, that is, the role of a poet.

O stony grey soil of Monaghan,

The laugh from my love you thieved;

You took the gay child of my passion

And gave me your clod-conceived.

[…]

Lost the long hours of pleasure

All the women that love young men,

O can I still stroke the monster’s back

Or write with unpoisoned pen

His name in these lonely verses

Or mention the dark fields where

The first gay flight of my lyric

Got caught in a peasant’s prayer.

While in the poem Kavanagh considers whether he can still write with “unpoisoned pen” about the environment he has come from, nonetheless he still can write—and think, and be free, even if his thoughts and words are bitter. The poem legitimised one’s dreams—demands—for some form of self-expression, critical for a child on the cusp of adulthood.

That Kavanagh did so by using the language of rural Ireland was important to us teenage readers. In the brilliant sonnet, “Inniskeen Road: July Evening”, Kavanagh’s expert use of colloquialism and ordinary speech demythologised poetry, certainly established his voice as very different, closer to our own, than say, the work of the poet preceding him in Soundings, WB Yeats. “Why should I blame her that she filled my days/With misery, or that she would of late/Have taught to ignorant men most violent ways”, wrote Yeats in “No Second Troy”; Kavanagh, a short few pages later, wrote, “The bicycles go by in twos and threes–/There’s a dance in Billy Brennan’s barn tonight.” “Inniskeen Road”, like “Stony Grey Soil”, depicts the poet as outsider. Here, he watches the couples off to the dance while he observes alone—alone, by virtue of his vocation as poet as much as anything.

I have what every poet hates in spite

Of all the solemn talk of contemplation.

O Alexander Selkirk knew the plight

Of being king and government and nation.

A road, a mile of kingdom. I am king

Of banks and stones and every blooming thing.

We enjoyed the simple ambiguity of “blooming”, its containing of a gentle swear word in Irish usage within a word evoking nature’s bounty. (“It was too blooming dull sitting in the parlour with Mrs Stoer and Mrs Quigley and Mrs MacDowell and the blind down and they all at their sniffle and sipping sups of the superior tawny sherry uncle Barney brought from Tunney’s,” says Mr Dignam to himself in “The Wandering Rocks” chapter of Ulysses, “And they eating crumbs of the cottage fruitcake, jawing the whole blooming time and sighing.”)

Kavanagh’s earlier poems are full of place names: Inniskeen Road; Mullahinsha, Drummeril, Black Shanko (in “Stony Grey Soil”). As he says in his famous poem “Epic”,“I have lived in important places”. “He gave the place credit for existing,” writes Seamus Heaney of Kavanagh’s early poetry, “and accepts it as the definitive locus of the given world.” Heaney goes on to say that Kavanagh “knows that the Monaghan world is not the whole world, yet it is the only one for him”, that is, the only one immediately available to him, and to be acknowledged for that fact. Reading Kavanagh in the 1980s was to receive acknowledgment and endorsement—in one’s own tongue—of the small places in which we lived. “Epic”, a sonnet, asks “Which was more important?”, what he terms “the Munich bother” (the Munich crisis of 1938), or a row over a field in Monaghan. Homer’s ghost answers the question: “I made the Illiad from such/A local row. Gods make their own importance.”

One sensed in the 1980s that there was something troubling, radical about Kavanagh, despite his presence in a Department of Education textbook. Kavanagh’s was a voice, in some ways, entirely appropriate to the times, his centrality to the experience of Soundings perhaps capturing the fissures and fault-lines in what was still an immature, emerging State. Ireland joined the European Union in 1973 and one witnessed a gradual transformation of Irish society through the 1980s with the next great watersheds arguably the election of Mary Robinson as President in 1990, the resignation of Bishop Eamon Casey in 1992 and the very rapid collapse of the Catholic Church as a central institution in Ireland in the years after, and the IRA ceasefire in 1994. Through all these tumultuous years, Soundings and Kavanagh can be said to have echoed the zeitgeist. Here we have a rural man desperate for a better, more creatively fulfilling life as the country sought to transform itself into a modern economy and Dublin sought to become a European capital. Kavanagh’s greatest poem, “The Great Hunger”, an epic of sexual frustration set deep in rural Ireland in the 1930s, was revived, significantly, in 1983 in an award-winning play by Tom McIntyre. The “great hunger” of the poem—described by Declan Kiberd as a “fierce anti-pastoral”—is not just that of bachelor farmer Paddy Maguire, it is of the entire nation. Kavanagh offered no recipes but his image of Maguire’s mother’s “knuckle bones … cutting the skin of her son’s backside/And he was sixty five” read in the 1980s as a stinging portrait of how “Mother Ireland”, and the iconography surrounding it, dating from the birth of the State, held back a new Ireland from being realised. “You flung a ditch on my vision/Of beauty, love and truth,” Kavanagh writes in “Stony Grey Soil”; in the 1980s, the sentiments of the poem reflected those of the many emigrants who quit seemingly backward Ireland for lives in London, Boston, and further afield, and for those who stayed accurately captured the struggling State.

In common with many writers of this period, Kavanagh drew aesthetically from Catholicism, as is evident in the poem, “Advent”, also part of the Soundings sequence. “We have tested and tasted too much, lover,” the poem begins, and this line was the first experience this reader had of that final word, “lover”, pronounced with utter seriousness and without sentimentality. The poem, again, pointed towards possibilities for this adolescent—framed, as it were, liturgically by Advent, the poem identified what “grown up” looked like.

Won’t we be rich, my love and I, and please

God we shall not ask for reason’s payment,

The why of heart-breaking strangeness in dreeping hedges

Nor analyse God’s breath in common statement.

We have thrown into the dust-bin the clay-minted wages

Of pleasure, knowledge and the conscious hour—

And Christ comes with a January flower.

Reading the poem in Catholic Ireland was a strangely liberating experience, for not only does love appear a grown up thing in “Advent” but so does belief. There was a shallowness perhaps and an ease about religion in 1980s Ireland, and faith seemed uncomplex and sentimental; Kavanagh treats religion much more seriously than the frequently philistine clergy treated it. Kavanagh here, and in many other poems, sought to identify the divine in the everyday, and simply to appreciate the divinity that appeared in “the heart-breaking strangeness” of the hedgerows. The poem has the quality of a Catholic prayer, but there is a properly mystical element to Kavanagh evident too. His use of the phrase “please God”, significantly appearing across two lines here (“please/God”), appropriates a convention in Irish talk to ask what pleasing God means: good behaviour, wonder at His creations, loving well and tenderly, appearing child-like in His eyes? This is a thoughtful poem and philosophically and theologically rich.

That same mystical element is very clearly evident in the final poems in the Soundings collection and among the final poems written by Kavanagh. Heaney brilliantly characterises the final phase in Kavanagh’s writing life, a phase that followed hospitalisation for lung cancer in the mid-1950s. Heaney notes a dramatic change in Kavanagh’s work of the final period so that “when he writes about places now, they are luminous spaces within his mind.” “We might say that now the world is more pervious to his vision than he is pervious to the world,” writes Heaney, his poetry now more to do with the “placeless heaven” than the “heavenly place”. The two Canal Bank poems capture this perfectly.

O unworn world enrapture me, enrapture me in a web

Of fabulous grass and eternal voices by a beech,

Feed the gaping need of my senses, give me ad lib

To pray unselfconsciously with overflowing speech

For this soul needs to be honoured with a new dress woven

From green and blue things and arguments that cannot be proven.

This is “Canal Bank Walk”. Heaney notes that the voice here is far from passive, despite the seeming desire to be enraptured; “pretending to be the world’s servant,” says Heaney, “Kavanagh is actually engaged in the process of world mastery” in the poem. The same may be said for the other Canal Bank Sonnet included in Soundings, “Lines Written on a Seat on the Grand Canal, Dublin”. It is not the world that is commemorated in the poem but the conscious mind acting on that world. “No one will speak in prose/Who finds his way to these Parnassian islands”, he writes; the poem’s emphasis falls on the vigorous, energetic, playful mind and the poet’s speech, not the beautiful canal itself. This particular poem, though written about a memorial seat, suggested an appropriate way to commemorate Kavanagh—a presence on the Dublin streets for many years—after his death. Today a statue to him sits on a bench at the side of the canal on Mespil Road.

As assessment of Kavanagh’s work must countenance the body of poor work he produced especially in his middle years, some of it pure doggerel, though McGahern, quoting Auden, defends it as “the weapon of the outsider, the anarchist rebel”. In the final analysis, along with the poems in Soundings, “The Great Hunger” and “Lough Derg” (written around the same time) are wonderful and necessary long poems. Also, the final poems are luminous, and deeply affecting, and indispensable. We may consign the early poems perhaps as poems of post-Revivalist readjustment, though many of the best retain still some power. One way or the other, Kavanagh, one senses, is not much read now. A number of years ago, he dropped from the secondary school curriculum. It is perhaps that his time has passed, that his country has grown up enough not to need his voice so much. But for many Irish people, especially those who knew and loved Soundings, he is in some way their poet—perhaps the only poet they remember and the only poet whose lines they can quote—and the voice of a particular part of their childhood.

Further Reading

Two books are indispensable. Kavanagh’s Collected Poems is published by Penguin and nicely edited by Antoinette Quinn. Quinn has also written Patrick Kavanagh: a biography, a magnificent and essential work. Readers wishing to explore the mystical element in Kavanagh are directed towards Tom Stack’s anthology, No Earthly Estate: God and Patrick Kavanagh (Columba Press, 20020). Seamus Heaney’s terrific essay, “The Placeless Heaven: another look at Kavanagh”, appears in his book of essays, The Government of the Tongue (1988). John McGahern’s response to Patrick Kavanagh: Man and Poet edited by the poet’s brother, Peter, is more interesting than the book reviewed and can be found in Love of the World: Essays. There are some illuminating remarks on Kavanagh and “The Great Hunger” by Declan Kiberd in Inventing Ireland. Having been out of print for years, Soundings returned to print in 2010 due to popular demand. It is readily available.

Dr Richard Hayes is currently Vice President for Strategy at Waterford Institute of Technology. He was previously Head (Dean) of the School of Humanities also at WIT. He is a graduate of Maynooth University and University College Dublin, Ireland, from which he received a PhD for a thesis on American theatre. He has lectured in a number of higher education institutions in Ireland and abroad and has published articles and essays on many aspects of Irish and American literature.

Dr Richard Hayes is currently Vice President for Strategy at Waterford Institute of Technology. He was previously Head (Dean) of the School of Humanities also at WIT. He is a graduate of Maynooth University and University College Dublin, Ireland, from which he received a PhD for a thesis on American theatre. He has lectured in a number of higher education institutions in Ireland and abroad and has published articles and essays on many aspects of Irish and American literature.

Photo credits: Richard Hayes

Nice essay, Dr. Hayes. Brings back a lot of good memories. I had to send it to my old classmates from UCD where ages ago we did our MA degrees in Anglo-Irish Lit. Gus Martin was one of our professors, and we studied a lot of the poems you mention with him. He had a Richard Burton voice and would pace around the room declaiming the lines–usually from memory. I believe he had Yeats’ entire catalog committed and advised us all that we should have a great store of poems memorized. “Mnemosyne is the mother of all the Muses,” he said. We also ran into him in the pub from time to time. Once he opened the door to a snug at some pub-maybe Mulligan’s, where a few of us were drinking pints. He opened the door and said, “Is this the way you do research?” and closed it again. I was very sorry to hear of his passing. I remember Paddy Kavanaugh’s bench, though back then there was a plaque but no statue. Now I want to go back and read those poets again.