Recollections of Noël

Recollections of Noël

By Louise Peloquin

When the priest at Notre Dame de Lourdes church * put on violet vestments on the first Sunday of Advent, Noël was on the horizon.

My family attended French Mass which always included traditional hymns from Québec and France. Our Advent favorite was:

“Venez Divin Messie

Nous rendre espoir et nous sauver.

Vous êtes notre vie,

Venez, venez, venez!”

(Come Divine Messiah

To give us hope and save us.

You are our life,

Come, come, come!)

The glorious sound of bellowing organ chords filled the church as we sang along with the choir. One of my altar boy cousins had the honor of lighting the first purple candle on the Advent wreath. Plumes of pungent incense tickled our noses and added to the irresistible suspense. “Noël s’en vient!” (Christmas is coming!). It was the time to prepare our hearts and homes for “le Divin Messie”. My cousins and I lived in a two-family home in the Highlands. The sixteen-year age difference between the eldest and the youngest never inhibited fun.

The family home on Harvard St in the Highlands

Our Advent occupations included getting ready for “la Messe de Minuit” (Midnight Mass). Every willing youngster could have a role in the Nativity pageant. We all wanted to be part of the show, not only to don a special costume but also to stay up way past bedtime.

The most coveted roles – Marie, Joseph and the shepherds – were reserved for the best-behaved NDDL seventh and eighth graders. None of the young’uns protested. They knew seniority would come in due time and were quite satisfied to join the heavenly host of angels wearing sky blue satin gowns and silver garland halos designed by couturier mothers and nuns. I was once among the seraphs coiffed with a shirt hanger halo precariously tilted on my small head. It systematically slipped to my eyebrows but I nevertheless maintained a pious posture with hands crossed at the waist.

The army of angels could not remain upstairs for “la Messe de Minuit” because enthusiastic parishioners crowded the nave. So our big show consisted in trooping down the aisle to the tune of “Douce Nuit, Sainte Nuit” (Silent Night, Holy Night) then proceeding to the basement where the PA system aired the upstairs ceremony. Only Jesus’s parents and the two shepherds benefitted from church seating on three-legged stools inside the wooden crêche placed to the side of the altar. The sacristan made sure the evergreen garlands, poinsettia planters and large tinfoil star were a worthy decor to welcome “l’Enfant Jésus” (the Child Jesus).

During the pre-wide-screen-video era, we little ones had to visualize the pomp a few feet above our heads. We didn’t mind. At the end of the Mass we would file back up when the pastor switched on all the lights and placed the “Petit Jésus” statue in a bed made of planks covered with yellow straw. Marie and Joseph would contemplate the divine newborn and the whole congregation would break out in song. Joy and love became palpable.

“Il est né le Divin Enfant!

Jouez hautbois, résonnez musettes.

Il est né le Divin Enfant.

Chantons tous son avènement.”

(He is born the Divine Child.

Play oboes, resound bagpipes.

He is born the Divine Child.

Let us all sing His coming.)

When Midnight Mass was over, attendees lingered to wish one another “Joyeux Noël!” with smiles, handshakes and hugs. The army of angels went back to the basement to exchange its celestial garb for winter coats, boots and colorful handknit “tuques” (woolen hats). While helping the younger cherubs bundle up, the supervising nuns would insist on maintaining angelic conduct. A heartfelt “Oui, ma Soeur” (yes Sister) was the usual response.

After Mass, mothers accompanied children to the crêche. Everyone wanted to admire “l’Enfant Jésus” surrounded by Marie, Joseph and the two shepherds. Lights flashed as snap shots were taken and the organist continued the repertoire of “cantiques” (hymns) like “Minuit chrétien” (O Holy Night), “Les anges dans nos campagnes…Gloria in excelsis Deo”, “Dans cette étable” (in this stable).

Fatigue evaporated as churchgoers headed home for “le Réveillon”, the post-Midnight Mass family celebration consisting in a French-Canadian smorgasbord and singing. For us kids, the prospect of staying up long after “la Messe de Minuit” with our favorite playmates was most appreciated. During “le Réveillon”, the doors separating the two-family residence remained open. It was a magical time. An evergreen wreath with red ribbons dancing in the biting wind hung on the door outside. Inside, an “arbre de Noël” (Christmas tree) bedecked with multicolored lights, glass balls and shiny tinsel occupied the front hall.

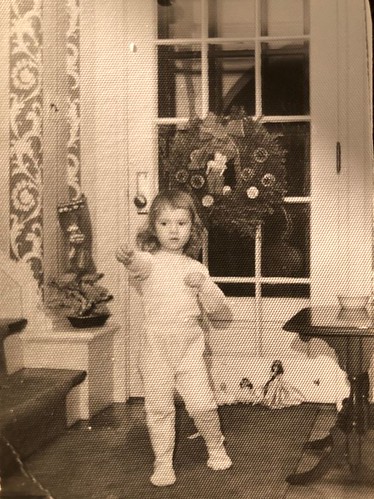

Happy Cousins at Christmas

On the living room wall hung an unusual wreath made of large pine cones encircling shellacked and painted paper mâché fruit. It looked real enough to make our mouths water. Had it been within my reach, I certainly would have plucked a few cherries and grapes. My physician father had received the ornament from the mother of a young patient he had saved by performing emergency surgery on a ruptured appendix. When the holidays were over, my mother would store the work of art in safekeeping. One December, when she noticed that the shellacked paint had chipped and the cherries and grapes had begun to droop, she salvaged the bananas, apples and pears to prolong its lifespan. How sad we were when the cornucopia wreath eventually disappeared from the holiday scene. The young patient had grown up and his parents had moved out of town. For years thereafter, Papa received a “carte de Noël” (Christmas card) expressing their “gratitude éternelle”.

Another patient contribution to our Noël decorations was a unique “Petit Jésus”. Papa had tackled an outbreak of pneumonia in a convent one year. The severe as well as mild cases had taken their course and every nun, old and young, recovered. They decided the care warranted a special “merci” – a baby Jesus made of beeswax. His upturned mouth was delicately painted in the palest of pinks. Blonde eyebrows over opalescent lids showed off blue glass eyes. A tuft of soft, fluffy blonde curls crowned his round head. The first time we laid eyes on this “Petit Jésus”, we were convinced he could read our thoughts so we tried to be “bons” (good) in his presence. Laying in the small wooden bed sculpted by “Pépère” (Grandpa), he became the showpiece of our crêche. Maman would always put him away in the basement along with the fruit wreath. But one dog day of summer turned our beautiful “Enfant Jésus” into an amorphous glob. Since he had been blessed by a priest, he remained very precious and we couldn’t possibly dump him into the trash. The wax figure had a proper burial in the back yard with a special rock to mark the spot. Long after, we kids said silent prayers there during our after-school games of tag and hide and seek. “Le Petit Jésus”, we thought, was still observing us with his blue glass eyes.

In most Franco-American homes “le Réveillon” was a culinary “fête” where expert cooks toiled beyond the call of duty to satisfy appetites and thrill palates. Specialties were served buffet style at our house. Crackers spread with homemade “cretons” (pork scrap pâté) were snapped up while the “tourtières” (pork pies) heated. My mother and aunt would compare their “tourtière” recipes and exchange tips on the most appropriate spicing. Cups of thick, bacon-rich “soupe aux pois” (pea soup) were passed around along with slivers of “pâté au salmon” (salmon pie). Drinks included fresh apple cider and Maman’s egg nog whipped up instinctively, never with a recipe. Since her passing in 2012, no one has managed to duplicate it. Adults spiked the concoction with a splash or two of brandy while we kids downed it like water.

“Le Réveillon” was meant to restore energy from the effort of attending Midnight Mass. It included desserts like apple and cranberry-raisin pies, as well as “tarte au sucre” (sugar pie) – a delectable maple syrup, brown sugar, heavy cream, butter, eggs and flour filling in the flakiest of crusts topped with a dollop of whipped cream.

Louise’s mother at the piano

Hot coffee, tea and cocoa helped everyone digest before the musical portion of “le Réveillon”. One of the family’s pianists would sit at the old baby grand, purchased by “Mémère” (Grandma) decades before at a flea market. Happy revellers joined in song belting out French and English yuletide carols. When my aunt and mother noticed droopy eyelids, the celebration wound up. We all complied knowing that the merriment would continue the next day. “Bonsoir, joyeux Noël tout le monde!” (Goodnight, merry Christmas everyone!). Cousins trooped up to their rooms. Parents expressed thanks and the doors closed on happy hearts and replete tummies. Once again, the two-family “Réveillon” had been “une belle fête” (a beautiful party).

Morning comes quickly when one retires in the wee hours. After “le Réveillon”, we were eager to discover what “le Père Noël” (Father Christmas) had brought. Yes indeed, we had often been naughty but we had become nicer and nicer as December 25th approached. There had to be something for us under the tree. Sure enough, colorfully wrapped boxes and bags were awaiting. My parents didn’t raid the toy store to cater to our every wish. Each of us received one. This was completed with a gift for the whole family.

Louise and her brother

One year, my brother and I received a “doctor set” – a bright red plastic satchel filled with medical instruments like a stethoscope, a thermometer, bottles of jelly-bean pills, cotton balls, a little scalpel. A family gift was a board game, an illustrated book or a badminton set to share with our cousins. Maman and Papa received artwork created under the supervision of the very patient Grey Nuns of the Cross at NDDL school.

After exchanging gifts and reluctantly getting out of our PJ’s, we helped Maman prepare the table. “Le jour de Noël” (Christmas Day) was a day for more family members to gather for an afternoon meal. My paternal “Mémère” and “Pépère”, along with several aunts, arrived with offerings. I remember Pépère’s box of individually-wrapped, cantaloupe-sized, pink Florida grapefruit and the aunts’ homemade fruitcake, fudge and snowman-shaped gingerbread cookies. The culinary creations had to look as good as possible before disappearing into hungry bellies. We sat down for the “repas de Noël” (Christmas meal) after saying the “bénédicité” (grace) with a special “merci” for the most precious gift of all, “être ensemble” (being together).

The menu included “tourtière” for those who couldn’t get enough of it. The “plat de résistance” (main dish) was either a repeat of Thanksgiving or a glazed ham decorated with cloves and pineapple slices. Papa would take out his sharpest knife and carve out paper thin slices of meat while explaining – “Les tranches minces sont plus digestes, plus faciles à mastiquer et vous en aurez plus!” (Thin slices are easier to digest, easier to chew and you’ll have more!) He was undoubtedly thinking of the guests with missing molars.

The spirited exchanges were always in French. “Parler français” was natural, especially since we had never heard our Québec-born grandparents speak English. After a lifetime working in New England mill towns, they certainly could “Parler américain”. But their thoughts were best fashioned in that wonderful French-Canadian vernacular which mirrored the language of Jacques Cartier and Samuel de Champlain. We kids grew up with its special music and vocabulary. Still today, it rings in our heads like a familiar tune.

At the end of the day, Mémère, Pépère and “les Ma Tantes” (the aunts), bid us “Bonsoir et à bientôt” (goodnight and see you soon). We would reunite on January 1st to receive Pépère’s “bénédiction familiale de la nouvelle année” (the new year’s family blessing), a French-Canadian custom – the head of the family ushers in the new year with prayers and good wishes for relatives, friends, the local community and the whole world. We would reverently bow our heads beneath our grandfather’s raised arms, convinced that the blessing would put the year on the right track. Ever since, we have felt Pépère’s presence during the “bénédiction”.

Many Noël traditions remain as we meet to exchange greetings, gifts and lots of food. Some Franco families still organize a “Réveillon”. But the pageantry and magnificence of “la Messe de Minuit” belong to the era when many Franco-American parishes served the city of Lowell.

* NDDL Parish was founded in 1908 to cater to Lowell’s South Common district Franco-Americans. The house of worship on Church Street opened in 1962 and was closed in 2004.

The Author

A lovely window into a French Canadian Christmas in Lowell.

Merci, Louise! Vivid portrait of Noel’s past like those I remember.

Sweet & precious Memories of a wonderful family . Thank you for sharing a piece of your Christmas past . God bless.

Joyeux Noël ~ ♥️