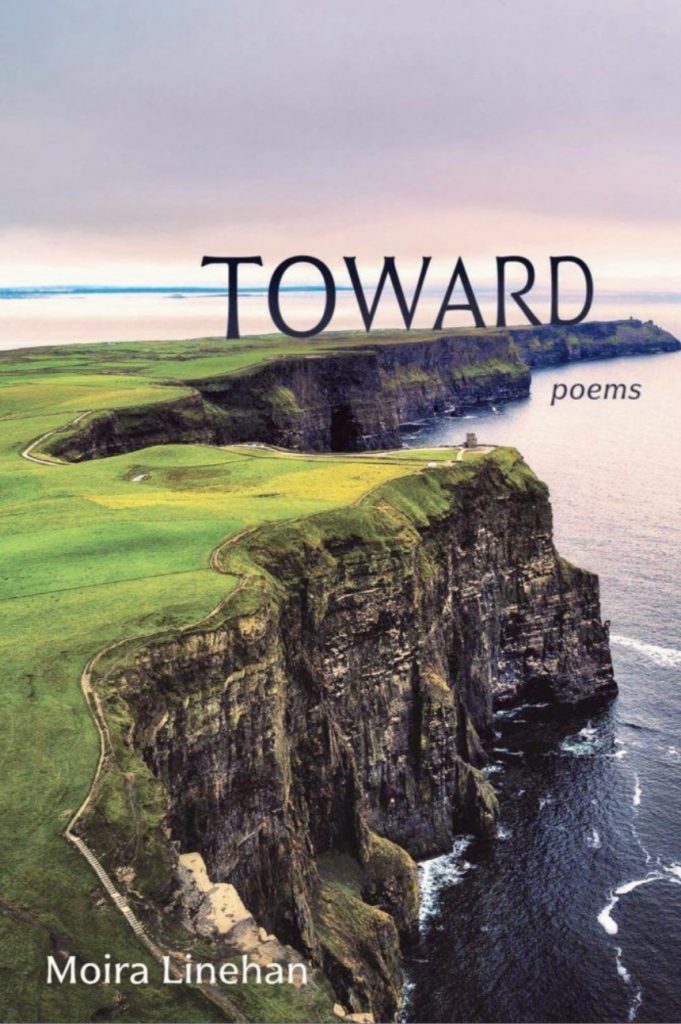

“Toward” and Other Poems by Moira Linehan

Moira Linehan has produced four collections of poetry, two of them in 2020: Toward from Slant Books and & Company from Dos Madres Press. Many of the poems the award-winning poet shares with Trasna were begun during her residencies at the Cill Rialaig Project in Co. Kerry and the Tyrone Guthrie Centre in Co. Monaghan. In these poems we witness a speaker embracing the connections between nature and place, language and art. They stir her soul. She senses them in the “language lost'” and the “something that remains,” as she says in the title poem “Toward.” Immersed in the country, she feels the calling that inspired the artists of Ireland to illuminate manuscripts, to raise the stones, to fish the wild sea, and to sing the tales that belong to the people.

The Tyrone Guthrie Center (photo credit Res Artis)

TOWARD

Tyrone Guthrie Centre

Co. Monaghan

I walk a mile down the road to Newbliss,

walk a mile away, walk the wooded path

along the lake and out onto the lane

winding between muddy green hills. I’m nowhere

but among mournful cows, their eyes bottomless

wells that know a soul’s dark nights. All their lives

cows stay put. One foot to the next I keep

moving, an end point always in mind: village,

next hillock, rounding the lake’s loop. On I walk

without being able to say why I must.

The language here has been lost, words like woods

cut down, hauled off or abandoned. Yet

something remains of those who spoke it. What

has always been beyond words, even when

they had their own. That’s where I’m headed.

BENEATH AN IRISH SKY

Having just arrived, I can’t say if it were days

of showers or just one storm—maybe no longer

than a fierce hour—left the ditches this slurry

of mud, slick and red-brown. A thick brush has spread

watery clouds, a gradient of black to rain-

grey, blurring in their hurry. These clouds, shrouds

unwinding over hillocks, or rising sky-

filled washes. Are they coming? Going? I worry

I’ll be caught without an umbrella so I turn

back to the house, though in my turning, turn

already from my purpose, having just arrived,

here for two weeks to be beneath a sky so vast

I can do nothing but be emptied—or is it

filled?—all my purposeful striding, stopped in its tracks.

When I look back at where I was, there’s a cloud

of a profile, its mouth a crescent moon’s

open gape. Bright light radiates from behind

its other cheek, no sun visible but no doubt

there. Sunday’s Gospel about the Prodigal Son

or, depending how you read it, the Prodigal

Father. No need to walk any farther. Just look up—

north, west, south, east—there’s your inheritance.

Residencies at Cill Rialaig Arts Center (photo credit Residencies at Cill Rialaig Arts Center)

THE ART OF MANUSCRIPT ILLUMINATION

Before they were monks, they were fishermen,

they were sailors, they knew the knotting of ropes,

how to tighten, how to loosen, eyes closed,

could interlock knots into nets, hands moving

over and under, around and back. Twisting

and turning, that rhythm flowing in and out

through their hands, illuminating the texts

they copied, margins set off with fretwork

and lacework, letters entwined with tendrils

and vines, grapes for the picking. I am the Vine,

they wrote, wrapping serpents around chalices.

… So must the Son of Man be lifted up.

Their homeland’s art—roadside crosses and pendants,

sweaters and bowls—in metal, enamel,

stitchwork and stone. Spirals and cables, left

twist and right. Art they made, art they wore.

Down through the ages, art at their fingertips,

eyes closed, these monks who knew the knotting of ropes.

WHERE THERE’S A HISTORY OF FAMINE

They’re always eating the grass.

One or two look up, startled, when I walk near.

They go on chewing.

Four o’clock one afternoon I hear a herder whistle.

His sheep come panting.

What does he have that they want?

Locals said it was coming,

the hurricane off Bermuda, turned this way.

All week winds had moaned.

Now screeching, they huddle round the cauldron of this cottage.

Through the night they howl.

The surf’s pounding’s drowned out.

Next day, the winds come off the cliffs.

They swell the waves, march them toward the West Cork hills.

The waves spume white froth.

Heavy, black-brimmed clouds follow after in endless parade.

I climb toward land’s end.

Winds won’t let me walk straight.

The sky’s clearing. I chance it.

I’ve not yet walked down to the abbey’s ruins.

Crows raise a ruckus,

flush a feather-thin pheasant with its hurrying trail of tail.

Only the well-fed

could find meat on those bones.

A Famine’s reach—like this land.

Where the heavens lower their weight on dark clouds.

The bay and rain blur.

The horizon, a vast front for thousands of miles of sea.

Where those left built cairns

at the backs of their mouths.

GENEALOGY

In memory of Honora Buckley Linehan

July 19th, 1860,

the census for Easton, Massachusetts.

The fourth child of Daniel and Catherine Buckley,

Honora—my grandmother—appears

a month old. Add four boarders—John Haydan,

Dan Rierdon, Pat Connell, Ed Sweeney. All

born in Ireland. All in their twenties. Labourers

says the record. Honora’s father, too.

On that same day in the dwelling next door—

three families, thirteen names, the youngest

John Linehan, new-born son of Margaret and James.

- The Buckleys still have four boarders,

though the names have changed and they’re much younger.

There’s more detail of their work: works on hinges

this census says of Honora’s father.

Works on railroad, of three of the boarders

while the fourth one farms. Home for Honora,

where so many would come and go. Imagine

the stories of longing she’s hearing, all

in a language with no word for emigrate. Exile,

the closest they have. Each night at dinner,

Honora coming through that swinging door,

carrying bowls of potatoes boiled with cabbage

out from the kitchen into those stories

about the land they’d left, the mothers.

- Now Honora’s father sells milk.

Eleven boarders work in the shovel shop,

the stories, now multiplied three-fold.

Now the Linehans own the place next door.

James and his oldest, John, work in the hinge shop.

I know what I want next and there it is

in the state archives: July 7th, 1885—

Honora marries John, the boy next door,

which is where I wish this story could pause

so my grandmother could speak, say what home meant

when hers stood next door for the rest of her life

while inside she carried twenty-five years

of exile, the longing of who knows how many

for the ones they’d never see again.

After hearing those stories, what mother

would ever let go of her child? Or worse,

ever let her child get too close?

1910. Number of children born this mother:

10. Number of children living: 8. My father,

now a name on the census, my father

who grew up her youngest, though not her last.

She died the summer before I was born.

But hadn’t I been there all along,

for what story ever starts fresh and clean?

Straight and clear the path through the archives

back to Honora. And back to those boarders,

the stories that exiled her, as she’d tell them

again and again in the ways she did,

and did not, hold my father. He held me.

Moira Linehan is the author of four collections of poetry: IF NO MOON (2007) and INCARNATE GRACE (2015), both published by Southern Illinois University Press. IF NO MOON won the 2006 Crab Orchard Series in Poetry open competition. Both books were named Honor Books in Poetry in the Massachusetts Book Awards. In 2020 she had two other collections published: TOWARD from Slant Books and & COMPANY from Dos Madres Press. In addition to being awarded residencies at the Cill Rialaig Project in Co. Kerry and the Tyrone Guthrie Centre in Co. Monaghan, Linehan has also been given residencies at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and the Whiteley Center on San Juan Island, WA.

Moira Linehan is the author of four collections of poetry: IF NO MOON (2007) and INCARNATE GRACE (2015), both published by Southern Illinois University Press. IF NO MOON won the 2006 Crab Orchard Series in Poetry open competition. Both books were named Honor Books in Poetry in the Massachusetts Book Awards. In 2020 she had two other collections published: TOWARD from Slant Books and & COMPANY from Dos Madres Press. In addition to being awarded residencies at the Cill Rialaig Project in Co. Kerry and the Tyrone Guthrie Centre in Co. Monaghan, Linehan has also been given residencies at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and the Whiteley Center on San Juan Island, WA.

Credits: From Toward, Slant, 2020: “Toward,” originally in Crab Orchard Rev.;” “Beneath an Irish Sky”; “Where There’s a History of Famine,” Nimrod International Journal; “Genealogy,” Notre Dame Rev. From Incarnate Grace, Southern Illinois University Press, 2015, “The Art of Manuscript Illumination.“ Toward is available at Slant Books’ website

https://www.slantbooks.com/books/toward

I enjoyed Moira Linehan’s poems, especially “The Art of Manuscript Illumination” for its recognition of artists who were long-time monks–or possibly newer members of the monastery, those who lives began elsewhere and who came to their art from other avenues. The poem also acknowledges the talents of those whose gifts led them to create beauty in their immediate situations.

Thank you for the generous sharing of these poems. I enjoyed the “ mournful cows with bottomless eyes”. The poems bring the weather and landscape of Kerry to life. I also loved Genealogy, telling a family’s story in a compelling and brief way. very enjoyable xx