‘Introducing John McGahern’ by Dr. Richard Hayes

The month of November, with its decreasing hours of daylight and lengthening nights, offers an opportunity to turn inwards. It is traditionally a month in Ireland when we remember those who have passed on, indeed the 1st and 2nd of November are known respectively as All Saints and All Souls days. On Trasna, our focus this month will be on Irish writers who have passed on and who are remembered by contemporary writers and scholars.

In this article, Dr. Richard Hayes considers the output of the writer John McGahern, (1934 – 2006), and argues that McGahern is the greatest novelist since Joyce, with an importance not only as an Irish writer but as a world writer of great substance.

It is not a great surprise that John McGahern is so beloved as a writer in Ireland but less well known and celebrated outside it. His work, largely set in Ireland in the period, roughly, between the end of the Second World War and the new millennium, captures so well the nuances of social behaviour in Irish country parishes that it is hard to figure how a non-Irish reader—even a reader from urban Ireland—could make much sense of it. If Dublin can be recreated from the pages of Joyce’s Ulysses, mid-twentieth-century rural Ireland could be rebuilt from the novels and stories of John McGahern; he captures with incredible understanding an Ireland that towards the end of the twentieth century was rapidly disappearing and is now, largely, gone. Yet McGahern is Irish in the same way that Tolstoy is Russian; Ireland is the landscape out of which his work emerges but his fiction grapples with ideas and themes that transcend that locale. He is Ireland’s greatest novelist since Joyce; he is also a world writer of great substance and belongs amongst the echelons of the greatest writers of fiction of the last half century.

John McGahern was born in 1934. (He is a close contemporary, therefore, of Alice Munro (b.1931), John Updike (b.1932), and Philip Roth (b.1933), and it is productive to consider him alongside that company, responding to similar social changes and intellectual and artistic trends.) He grew up in rural Ireland where his father was a policeman. His mother, Susan, died when he was ten years old in 1944. There followed a period of significant disruption, moves away from his childhood home and his father’s remarriage. His relationship with his mother is the gravitational force at the centre of his fiction and is revisited repeatedly in one form or another. “She never really left us,” he reflects in his final book, the non-fiction Memoir, a masterpiece of autobiography: “In the worst years, I believe we would have been broken but for the different life we had known with her and the love she gave that was there like hidden strength.” “When I reflect on those rare moments,” he writes, “when I stumble without warning into the extraordinary sense of security, that deep peace, I know that consciously and unconsciously she had been with me all my life.” When McGahern died in 2006 he was buried alongside his mother.

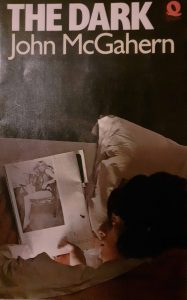

In his reflections on his mother he acknowledges, and respects, her religious faith, a faith he grew up with but did not share. In the final pages of his final book, he imagines walking with her in the country lanes. “I would want no shadow to fall on her joy and deep trust in God,” he writes, “She would face no false reproaches.” McGahern is obviously and demonstrably a “Catholic” writer notwithstanding his non-belief. “I have nothing but gratitude for the spiritual remnants of [my Catholic] upbringing, the sense of our origins beyond the bounds of sense, an awareness of mystery and wonderment, grace and sacrament, and the absolute equality of all women and men under the sun of heaven,” he wrote in 1993. While he celebrated the Catholic Church aesthetically, as it were, he found ridiculous and limiting the carry-on of the Irish Catholic Church and its collusion with the Irish State in the first decades of the State’s existence. McGahern grew up in the theocracy of post-War Ireland and was the direct victim of the Catholic Church following the publication of his novel, The Dark (1965). The novel was banned in Ireland for its sexual content and references to sexual abuse. This, together with McGahern’s marriage to a divorcee, was enough to have him dismissed from his teaching job at the instruction of the Archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid. McGahern did not publically condemn his dismissal and refused to protest about it, and discouraged others from doing so. He saw the whole affair as preposterous and therefore not worth acknowledging, and at the same time unreflective of the real life of people in the country: in Ireland at the time, “a childishness in religion and politics and art was encouraged to last a whole life long,” he writes in an essay, “Censorship”, and “it is only fair to say that most people were untouched by all this and went about their sensible pagan lives as they had done for centuries, seeing it as one of the many veneers they had to pretend to wear like all the others worn since the time of the Druids.” McGahern’s great interest is in the hidden lives behind these facades, lives and emotional, psychic forces that are often times as hidden from the protagonists as from the rest of the world.

McGahern was an accomplished essayist; readers are directed towards an excellent collection of his non-fiction, Love of the World: Essays, as well as to the aforementioned Memoir. He also produced a distinguished body of short stories, the most recent collection of which is Creatures of the Earth: New and Selected Stories, published just before McGahern’s death. His magnificent story, “The Country Funeral”, is as good as any story written in the second half of the twentieth century. “Korea” was made into a film in the 1990s.

But McGahern’s greatest achievement lies in his novels. The Dark was his second published book; his first was The Barracks (1963). Both draw heavily on his early life. The Barracks tells the story of Elizabeth Reegan, second wife of a country policeman. Elizabeth has been a nurse abroad but has returned to Ireland to settle down, which she does uneasily with Reegan. The opening pages of the book, according to one commentator, “contain some of the best prose written in English in the second half of the twentieth century”:

Mrs Reegan darned an old woollen sock as the February night came on, her head bent, catching the threads on the needle by the light of the fire, the daylight gone without her noticing. A boy of twelve and two dark-haired girls were close about her at the fire. They’d grown uneasy, in the way children can indoors in the failing light. The bright golds and scarlets of the religious pictures on the walls had faded, their glass glittering now in the sudden flashes of firelight, and as it deepened the dusk turned reddish from the Sacred Heart lamp that burned before the small wickerwork crib of Bethlehem on the mantelpiece. Only the cups and saucers laid ready on the table for their father’s tea were white and brilliant. The wind and rain rattling on the window-panes seemed to grow part of the spell of silence and increasing darkness, the spell of the long darning-needle flashing in the woman’s hand, and it was with a visible strain that the boy managed at last to break their fear of the coming night.

McGahern’s method is visible in this passage. His works develop, in the way the passage above does, from a single image; his art in fact is founded on (as he explains in an important prose piece, “The Image”) the search for “the one image that will never come, the image on which our whole life took its most complete expression once, that would completely express it again in this bewilderment between our beginning and our end; and then the whole mortal game of King would be over, and all games.”

In the 1970s, McGahern published two novels, The Leavetaking (1974), a curious book about a young school teacher, and The Pornographer (1979), with both novels featuring protagonists who are rural migrants to Dublin. Both novels are in the first person and are the least of his books. McGahern returns to third person narrative and to rural Ireland in his masterpieces, Amongst Women (1991) and That They May Face the Rising Sun (2001). Amongst Women is arguably the greatest Irish novel since Ulysses. It centres on Moran, a veteran of the Irish War of Independence, his daughters and two sons, and his second wife Rose. “As he weakened, Moran became afraid of his daughters,” the novel begins: “This once powerful man was so implanted in their lives that they had never really left Great Meadow, in spite of jobs and marriages and children and houses of their own in Dublin and London. Now they could not let him slip away.” The prose throughout this great book is precise and temperate yet registers the great, elemental forces that move beneath the surface of the family and within Moran, a man both appalling and charming, loved and hated by his children in equal measure. At one point, Moran strides through the fields he has farmed all his life.

It was like grasping water to think how quickly the years had passed here. They were nearly gone. It was in the nature of things and yet it brought a sense of betrayal and anger, of never having understood anything much. Instead of using the fields, he sometimes felt as if the fields had used him. Soon they would be using someone else in his place. It was unlikely to be either of his sons. He tried to imagine someone running the place after he was gone and could not. He continued walking the fields like a man trying to see.

Amongst Women is a work of extraordinary compression, and McGahern has described in a number of interviews the many hundreds of pages he discarded from the manuscript as he honed the book.

McGahern’s final novel, That They May Face the Rising Sun (published in the US as By the Lake), appeared in 2001. The book is a magnificently rich, quite serene, meditative depiction of a rural Irish community, mediated in some senses, by a couple who live there who resemble McGahern and his wife. If there is bitterness and rage (at the cynicism of Ireland’s power-holders and others) in the early books, here there is acceptance and generosity. This is not to say that all is light in the novel—we witness some scenes of extraordinary cruelty and nastiness—but the whole is marked by a sober recognition and forgiveness. The novel is attuned to the seasonal changes on the lake around which the community is built and the rhythms of the book are, in a primitive way, “religious”. A character is buried in the novel, and the community insists that “He sleeps with his head in the west… so that when he wakes he may face the rising sun.” This sense of the small, insignificant community in rural Ireland as somehow connected to deeper universal rhythms sums up McGahern, a writer of rural Ireland, certainly, but also a writer of and for the world.

Lough Rynn, Co. Leitrim, Ireland

Lough Rynn, Co. Leitrim, Ireland

Dr. Richard Hayes is Vice President for Strategy at Waterford Institute of Technology. He is a graduate of St Patrick’s College Maynooth and of University College Dublin and has taught English literature, film and theatre studies at a number of higher education institutions in Ireland and abroad. He has published a number of articles and book chapters on American theatre, American cinema, Irish poetry and Irish literature. He is the creative director of the Eugene O’Neill International Festival of Theatre and a board member of the Waterford-based Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA).

Dr. Richard Hayes is Vice President for Strategy at Waterford Institute of Technology. He is a graduate of St Patrick’s College Maynooth and of University College Dublin and has taught English literature, film and theatre studies at a number of higher education institutions in Ireland and abroad. He has published a number of articles and book chapters on American theatre, American cinema, Irish poetry and Irish literature. He is the creative director of the Eugene O’Neill International Festival of Theatre and a board member of the Waterford-based Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA).

I was introduced to McGahern while studying abroad in the ’90s. He’s a remarkable writer and it’s nice to see him getting some attention here. I was lucky enough to see him on a double bill with Seamus Heaney in Boston a few years later, and you could feel the sense of surprise and discovery in the crowd, most of whom, I sensed, were unfamiliar with him.

This is a fine, comprehensive appraisal of McGahern’s work by one who clearly has an intimate, detailed, and insightful understanding of his material. His claim that this writer is second only to Joyce as Ireland’s greatest writer, is very persuasive, as is the parallel with Tolstoy, an interesting and merited comparison, in theme and setting, if not in scale. I love the chosen passages, especially the magical piece from The Barracks, which, in itself, is enough to recruit new readers. I met McGahern in a pub many years ago, and he is as striking in person as he is on the page. Thank you Richard, for sending me back to him.

John McGahern touched soul and I held THAT THEY MAY FACE the RISING SUN to my heart long after the final passage.

This tribute brought a similar feeling.

Thank you Richard Hayes.