The Poetry of Mapmaking: Retracing Maps of Northern Maine and Elsewhere

The Poetry of Mapmaking:

Retracing Maps of Northern Maine and Elsewhere

By Christine O’Connor

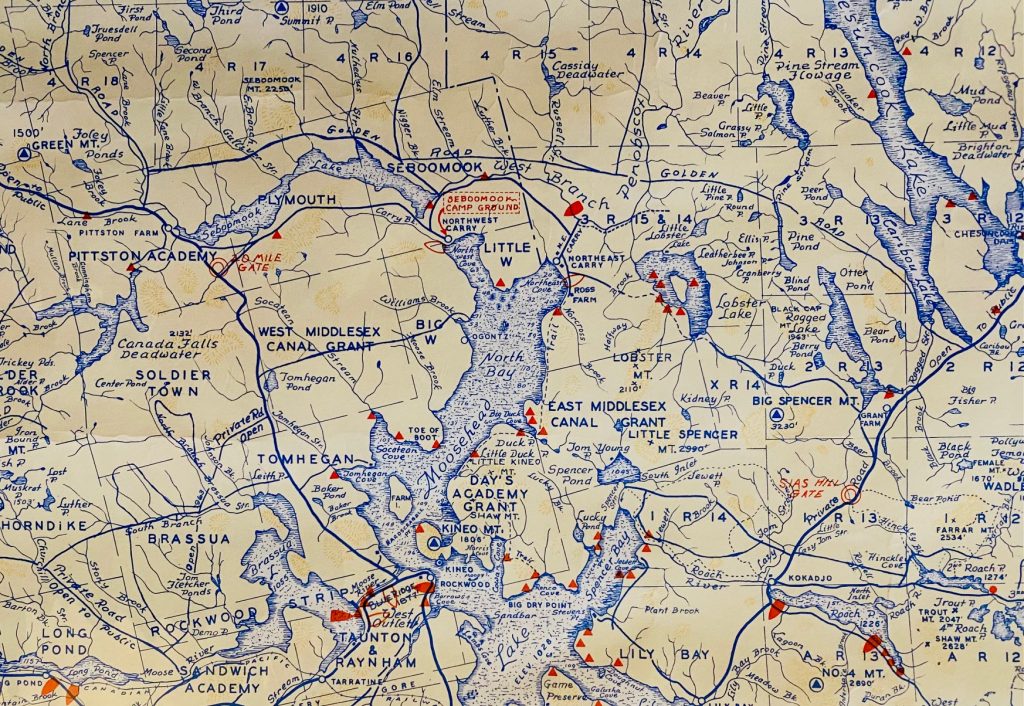

Detail from Phillips’ Map of the ‘Moosehead – Allagash Region of Northern Maine’ (1978)

This past summer I visited Harding’s Bookstore in Wells, Maine. It was the first time since the start of the pandemic. Despite my two-year absence, its aisles remained as familiar as a well-worn path in the woods. Straight ahead, through a low doorway and a sloping floor, past a large room on the right, and a small one on the left was Nature Writing. I picked up an illustrated sketch book for some younger cousins; Walter Harding’s biography of Henry David Thoreau, and a hard-covered edition of Sigurd Olson’s The Lonely Land.

I had only recently learned of Olson’s book from watching a Joe Robinet video, a popular YouTube bushcrafter I follow, as he canoed and camped in Canada’s Wabakimi Provincial Park. I had to pause it a couple of times to see what Joe was reading in his hammock after a day of paddling. Now, here it was, almost magically waiting for me on the shelf. In the early nineteen-fifties, Olson traveled some 500 miles in upper Saskatchewan retracing the old routes of the voyageurs: “There are few places left on the North American continent where men can still see the country as it was before the Europeans came, … but in the Canadian Northwest it can still be done.”

Other favorite spots awaited: Literary Criticism in the little room to the left of Biographies (almost forgot about the step there); the collection of books on the history of Ireland in the large front room (I confess it’s always annoying when some of these titles appear under a marker for Great Britain); the poetry section not far from where the owner has his desk (I scan for a favorite – Elizabeth Bishop); the sections on mountain climbing, New England history, Canadian history, essays, languages, philosophy. Do our books tell a lot about who a person is, or who they hope to be?

Last stop at Harding’s: the map room. Lots of things changed because of COVID-19, and Harding’s map room can be added to the list. It used to have prints, magazine ads, botany sketches, Harper’s Weekly illustrations, and most of all, maps from all over the world. Books now occupy the room’s center; and the maps are just local, as in Maine. Nevertheless, the ability to wander, linger, and pause on these prints is not lost. I brought a friend to the map room – a first time visit for her – and slowly we made our way, counterclockwise through the room as I have done so many times now.

As we were getting ready to go, one map caught my eye. It was a 1978 Phillip’s Map of the Moosehead – Allagash Region of Northern Maine, detailing the headwaters of the Kennebec, St. John, and Penobscot Rivers. Unlike the yellowed eighteenth and nineteenth century maps, this one had slightly faded blue-inked lines, a scattering of red markers, and even a few splotches of canary-yellow. Its colors separated it from the other maps in the room, and although slightly faded, there remained a vibrancy to them.

The small splashes of red marked campsites, flying services, fish hatcheries, and launching ramps. This was meant to be a working map, the kind that’s tucked into tackle boxes, knapsacks, or the inside pocket of an old coat. Beneath the cellophane wrapping I could still see the folds, and sense the many times it was opened and closed along them.

The map’s thin lines curled around familiar lakes and formerly traveled trails. Instinctively, my finger traced the crisscross of routes 15 and 11; 9 and 16. With little effort, I was again in the back seat in my uncle Sid’s old, Toyota Camry, heading for the Maine woods. When Sid was in his seventies and early eighties, after an extended career as a mechanical engineer, he began taking trips to the Northwoods of Maine. Typically, a few of us would break away from our months of summering on York’s sandy beaches, and travel with Sid to the state’s Moosehead – Allagash Region. Those trips became epic. Like Thoreau, we were eager to experience the wildness of a true wilderness. “Nature is a real tonic,” Sid would often say. So, each summer, we began spending time at different hunting and fishing camps in the region.

Along the way, we’d travel through an array of small towns: Bangor, Old Town, Gilford, Monson, Millinocket, Greenville; places where roadside diners served turkey dinners with peas and mashed potatoes; where Coca-Colas still came in glass bottles; and Saturday nights featured a bean supper at the local parish. Each had a general store with well-worn wooden floors, racks of old postcards, and gas pumps that haven’t operated in decades. Here, nostalgia filled the air, and mingled with the smells of pine and the smoke of stovepipes.

Sidney (Sid) E. Stirk on Little Lyford Pond

My uncle was born in 1918, and when we traveled through these towns nearly one hundred years later, they likely didn’t look all that different over those many years. These were places where authenticity had not yet been traded for the vagaries of modernity, and the same could be said for Sid. While a Yankee sensibility had become as old fashioned as the pocket protector he still wore; manners, truthfulness, and hard work always defined Sid. The first time we arrived in Millinocket, there was an immediate, symbiotic connection between Sid and this region, as each of them, like the faded blue ink of the Phillips’ Map, harkened back to an earlier time.

On the map were several points of intersection: rivers to lakes; backroads to by-ways; the boundaries of two very different countries; but, there were also unseen points of intersection, where my memories of time spent in that region meet the topography depicted. Within its thin lines, as ephemeral as a lake’s early morning mist, were the memories of these past trips to the Northwoods: a pocket knife older than me (Sid used it to cut fishing line); a float plane landing on Lake Nahmakanta (in Abenaki it means “many fish”); the dust kicked up from the old logging roads we traveled; signing the cabin’s guest book (how signatures change over time); a swimming hole or was it a fishing hole deep in the primeval forests; branches thick with Old Man’s Beard; ground covered in white Reindeer moss — the indescribable beauty of it all; the plunk of a lure hitting the water; the Zen of paddle strokes; spotting a moose (and the “sweet sensation of joy” Bishop wrote of); the handle of an old fridge in a log cabin (a chilled IPA awaits); playing cards under a kerosene light (it’s a flush!); a body at rest after a day of hiking; a crackling fire; the haunting cry of a loon; Johnny Cash tunes played on the ukulele; and the spectacular reveal of the universe beneath these, the darkest of skies.

Along with the few books tucked under my arm, I decided I had to get this map, and left Harding’s with that familiar feeling of excitement that comes with purchasing things that already have a history to them.

* * *

Like other artifacts left from those summer months, I had forgotten about my map. But as we slid into that dark, leafless time of year, I grew restless. Another strain of COVID-19 was identified, mask mandates were reinstituted, and infection rates surged. At home, the cultural divide between our country backroads and inner-cities grew; and all around the world democracies were under attack. As we were about to start a new year, a sense uncertainty took hold.

I thought of my uncle – born into an earlier pandemic, Sid started life in a century defined by anarchy, the rise of fascism, lynching, segregation, suffragettes, and world war. The signposts of our times were not new; and no matter how far we travel, we always seem to find ourselves at a familiar crossroad. When we feel we’ve lost our way, maps can redirect us.

So, maybe it was these feelings of uncertainty and unrest that caused me to retrieve my map from Harding’s and begin to study it. I quickly discovered Phillips’ Maps were the product of two brothers, Augusta (Gus) and Luther Phillips. The map making business started with Luther and included a collection of postcards. Gus joined his brother in the business, and after Luther died in 1960, took it over. A graduate of Phillips Andover and MIT, Luther was a photographer, postcard publisher, and mapmaker; while Gus became a Maine guide and operated a small, sporting camp. The maps grew largely out of their travels. Luther added pictorial details, Gus added paint colors.

In the years following his brother’s death, Phillips Maps continued to grow under Gus. Throughout the sixties and seventies Gus traveled in his blue AMC Rambler along the back roads of Maine delivering orders of maps and postcards to general stores, diners, gift shops, trading posts, and sporting camps. It’s speculated that at one time every hunting and fishing camp in Maine likely had a Phillips’ Map tacked to the wall.

These would have been the very camps we visited with Sid. Many sporting camps in Maine date back to the nineteenth century, and are available to visitors much as they were roughly 140 year ago – outhouses, woodstoves, kerosene lighting, remote log cabins on lake front locations. While other states – New Hampshire, Vermont, New York – offered private hunting and fishing clubs, in Maine these sporting camps were open to paying customers. As such, they are a unique part of Maine’s cultural and economic heritage. On the map, these places were smaller than the tip of my finger – their largeness and wildness resided elsewhere.

Tying fishing line with Sid

Scanning it, I lingered on some of the camps where we stayed and the places we explored– there was the beginnings of Baxter State Park, though Mt. Katahdin wasn’t included; further north was the Allegash River and Chamberlain Lake; to the south was Little Lyford and Big Lyford ponds; to the east Lake Nahmakanta, the Appalachian trail, and Mt. Wadleigh; and above Greenville was Moosehead Lake and Mt. Kineo.

One summer in the Northwoods my cousins and I climbed Mt. Kineo. Sid waited for us at its base. He would have been in his early eighties at the time. We had already done a lot of walking that day and he was careful to not over do it. The first recorded climb of Mt. Kineo was Thoreau’s in 1853. We likely used the same pine-needle covered path he took to its summit. Kineo, which is the Penobscot word for moose, appears on some of the earliest maps of the region – the earliest dating to 1761.

Thoreau is revered as a naturalist, an essayist, and transcendentalist; but he was also a land surveyor and mapmaker. Thanks to the work of John Hessler, the Senior Cartographic Librarian at the Library of Congress, a list of some six maps Thoreau copied was discovered in the margins of his Canadian Notebook. For over a decade, in the last years of his life, Thoreau studied the work of leading cartographers of the 16th and 17th centuries, reading their notebooks, narratives, and annotations. Like Sigurd Olson, Thoreau was also particularly interested in seeing the country as it was before the Europeans came. Thoreau is now recognized as one of the earliest historians of American cartography.

The word map comes from the medieval Latin “mappa mund,” meaning napkin/cloth, and world. Eventually it was shortened to map. Despite its epistemological origins, the earliest known maps, weren’t of our world, but of the heavens. These earliest maps detailed the black cosmos above; that unreachable place of planetary movement, cosmic dust, light reflections, solar eclipses, supermoons, and constellations. For the ancients, the dark skies were their blackboards, instructing them along fragile, chalk-lined trails from point A to B.

What’s thought to be the oldest known map dates to 25,000 BC and is engraved on the tusk of a wooly mammoth. In the famous Lascaux caves are maps of the nighttime sky, which mark the appearance of three bright stars: Vega, Deneb, and Altair. A cave in Spain maps the constellation Corona Borealis. The creation of maps is one of those uniquely important inventions in human history. Like the discovery of the wheel, the planting of a seed, a spark between two rocks, maps changed the world. Maps brought a certainty to travel that had been largely unknown, which in-turn led to trade routes, commerce, ports of entry, cities, economies, and wealth. By looking to the heavens, the ancients learned how to explore their world.

Maps still provide certainty in an otherwise uncertain world. What is the distance between Greenville and Millinocket? Fifty-seven, point seven miles. How high is Mount Kineo? One Thousand, eight hundred and six feet. How deep is Lake Namakanta? Six hundred and forty-six feet. Yet, there are other familiarities unknown to the mapmaker: the number of stories told as you travel along route 11-North; the number of paddle strokes to cross Little Lyford Pond; or the number of heart beats it takes to reach Mount Kineo’s summit.

View from float plane with Mt. Katahdin in the distance

While maps give us directions to things, they don’t guarantee we’ll find what we are after. On one of our trips north, we consulted our well-worn Maine Atlas for directions to North Haven, an island in Penobscot Bay. We were in search of Elizabeth Bishop’s summer residence, a yellow house called Sabine Farm. That summer, the old Camry followed the winding roads north along Maine’s rocky coast, passed her many finger-inlets, until we reached the “still pale bay” Bishop described in her poem named for the island of North Haven. Somehow at Rockland we mistakenly boarded the ferry for Vinalhaven, bringing to mind another line from that poem: “Revise, revise, revise.” On that day, however, such revisions weren’t possible.

Years ago at Harding’s I found a thin volume of North & South, the first collection of poetry by Elizabeth Bishop published in 1946. It went on that year to win the Pulitzer Prize. Its opening poem is “The Map.” The first of her poems to be published in the New Yorker, it is considered the start of Bishop’s oft-familiar subject of geography and place. She wrote the poem on a lonely New Year’s Eve in New York City. It was 1934, she had just graduated from Vassar, was living in Greenwich Village, and was at-home, sick with the flu. That night, as one year ended and another began, she studied a framed map of the North Atlantic detailing the Maritime Provinces, Greenland, Iceland, and Scandinavia: “More delicate than a historians’, are the map-maker’s colors,” it concludes. The poem “wrote itself,” she claimed.

Maps can be like poetry. They embrace the real and the imagined. They have an aestheticism as well as a function. They lead us forward and pull us back in time. They capture the contours of a country, and the depths and shallowness of its people. Maps connect us not only to places, but to each other: Sigurd Olson to the 18th century voyageurs; Joe Robinet to Olson – me to my uncle Sid, and our days spent in the wilds of Maine. Maps, like poems, are magical spaces where memories swirl like summer breezes, and fields of lupines bend in colors more delicate than a mapmakers.’

Photos by Christine O’Connor.

For more on Phillips’ Maps visit the Penobscot Marine Museum, Searport, Maine, which has as part of their collection, more than 30 original maps of regions of Maine and some 600 original postcards.

Thank you, Christine, for your wonderfully wide wandering cartographic excursion, revealing life itself to be a kind of mapmaking dream and maps themselves as found poems.

Christine I am reading about the bookshop , maps and your adventures with your cousins and Uncle Sid.

I am taking a lazy day on 3rd January ’22 and felt joy in being swept into another time and place.

Mile Buiochas/ A thousand thanks/ gratitude.

Loved it, Christine. Made me think that I need to do more family research……. Do you come across information on Passamaquoddy Indians in Maine? And a great uncle owned a camp in Maine. Where?? Happy Mew Year !! ML

Lovely piece, Christine. Made me reflect on how often, as a younger man, I pulled out a map to study and plan, see where I was going and where I’d been. It’s another thing that’s been lost since the advent of GPS. Now, we have a disembodied voice telling us where to go without actually seeing where we are in relation to everything else.

Your words brought back all the magic of maps, (as well as reminding me what a good guy Uncle Sid was).

Christine, my dear I loved reading about your adventures with Uncle Sid! What a delight, on this very dreary day to read about my Dad, A. D. Phillips and Uncle Luther. Thank you so much my dear!

Your writing is delightful and on a day like this, if I could I’d head down to your special shop just to hang out.

Sincerely,

This is a beautifully-voiced blending of old with new, past with present: “… branches thick with Old Man’s Beard; ground covered in white Reindeer moss — the indescribable beauty of it all; the plunk of a lure hitting the water; the Zen of paddle strokes…”

This piece reminds us that good writing is a time machine.

Chris, Outstanding synthesis of information, plucking the various strings and making literary music on the page. Also, the deep sense of valuing the particulars of places. And for Howe blog followers, northeastern America is the immediate neighborhood, speaking continentally. I don’t know about other readers here, but I never get past the feeling that I’ve missed most of what New England has to offer even though I’ve been down a lot of back roads in the region since I got my driver’s license in 1970. I’ve got a map of the Maine coast behind from the Maine Coast Heritage Trust, a reminder that there are places to go.