William Clark and Abraham Lincoln

Friday’s Lowell Sun had a story by Emma Murphy (“Does pocketwatch put Lowellian at Lincoln’s death bed?”) about Jonathan Ladd, a Civil War soldier from Lowell who may have been present in the room where Abraham Lincoln died on April 15, 1865. I’m quoted in the story saying I was not aware of the Jonathan Ladd story but that another man from Lowell, William Clark, was the usual occupant of the bed in which the President died. Here’s the story of William Clark, some of which has been posted on this site previously:

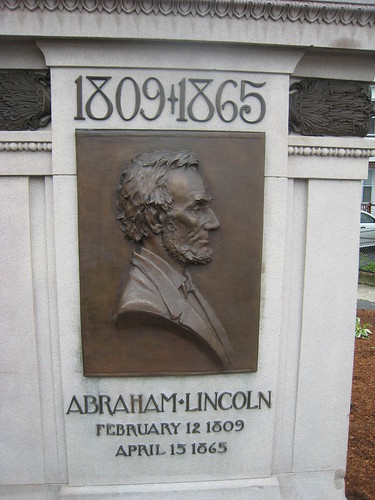

Abraham Lincoln Monument, Lincoln Square, Lowell, Mass.

On April 14, 1865 – Good Friday – Abraham Lincoln went to Ford’s Theatre. As he watched the play from his presidential box above the stage, John Wilkes Booth shot him in the back of the head. Lincoln was carried out of the theatre and across the street to William Petersen’s boarding house. There, they lay the barely-alive president in the nearest bed, one usually occupied by 23-year old William Clark. Lincoln never regained consciousness and died a few hours later, early in the morning of Saturday, April 15, 1865. (Coincidentally, the calendar cycle has the anniversary of Lincoln’s shooting and death, falling on Good Friday and the following Saturday, just was in 1865).

President’s Box at Ford’s Theatre

Ford’s Theatre

Like so much else that happens in the world, there was a Lowell connection to Lincoln’s assassination. That would be William Clark.

William Clark of Lowell, Mass.

Clark was born in Lowell in 1842. His father, Tilton Clark, worked for the Boston & Lowell Railroad, and died the year after his son’s birth in a fatal work accident at the railyard. In April 1861, William enlisted in the Union Army and served through most of the war. Due to illness, he was discharged from his regiment but he obtained work as a clerk in the War Department in Washington. He rented a room in William Petersen’s boarding house on Tenth Street, just across from Ford’s Theatre.

Petersen House

Clark was out on the evening of April 14, 1865. He returned home to find great commotion at the Petersen house and was unable to get to his room.

The bed in which Lincoln died, usually occupied by William Clark of Lowell

William Clark’s bedroom from main hallway of boarding house. Bed at lower right.

After President Lincoln expired, his body was removed from Clark’s room and everyone departed. But as Clark related in a letter to his sister in Lowell just a few days later, his room had become a type of national shrine. Here is some of what he wrote:

Since the death of our president hundreds daily call at the house to gain admission to my room. Everybody has a great desire to obtain some memento from my room so that whoever comes in has to be closely watched for fear that they will steal something.

William Clark moved back to Lowell and then relocated to Boston where he became a real estate agent. He died in 1888 at age 46 of heart failure.

Clark Family grave, Lowell Cemetery

One additional Lowell connection to Lincoln’s assassination: Lowell’s Ladd & Whitney Monument, the granite obelisk that sits in front of Lowell City Hall and which commemorated Luther Ladd and Addison Whitney, two young soldiers from Lowell who are considered the first soldiers to die from hostile fire in the American Civil War, was to be dedicated on April 19, 1865 – the fourth anniversary of the Baltimore riot in which they lost their lives. Due to Lincoln’s death, the dedication ceremony in Lowell was postponed. It was eventually held on June 17, 1865, the anniversary of the battle of Bunker Hill.

Ladd & Whitney Monument

Thanks, Dick. Fascinating read.

You write: “Like so much else that happens in the world, there was a Lowell connection to the Lincoln assassination.” The first part of that is weirdly true. I’m sure many–or all–of us can find instances of that. One quick example:

In the mid-1980s, when my wife & I had been residents of Lowell for only a short time, we were in Colorado, passing thru a small frontier town in the Rockies, population about 200. We wandered into a quasi-antique store. Amid the jumble of mostly cast-off rummage I found a) an old Ayer “medicinals” catalog and b) an assortment of bottles embossed with Hood of Lowell.

Just sayin’.