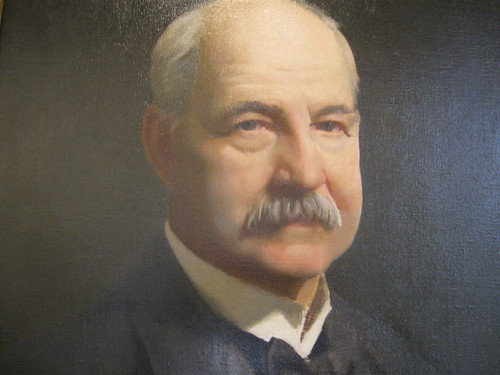

Lowell People: Moses Greeley Parker

This is the first in an occasional series of posts about historic figures from Lowell.

Moses Greeley Parker was born in Dracut, Massachusetts, on October 12, 1842. His father was Theodore Parker, his mother was Hannah Greeley Parker. Theodore owned a farm in Dracut and had the reputation of being very industrious. He recognized the growth potential of the new neighboring community of Lowell, and became an early investor in real estate there, although the Parker family was not particularly wealthy.

Theodore and Hannah had two children: Moses and Mary Greeley Parker, who later became Mrs. Leonard H. Morrison. Theodore had been married previously to Eldad Carter of Wilmington, Massachusetts. Eldad died after the birth of the couple’s first child, Theodore Edson Parker, who would be the half-brother of Moses.

Moses grew up on the family farm as an intelligent and inquisitive young man. He attended school in Dracut for the early grades, but the family realized his academic potential and sent him to the privately run Howe School in Billerica and then Phillips Academy in Andover for his later schooling.

At age 18, Moses became a school teacher, holding jobs in Hudson and Pelham, New Hampshire. At the same time, he began an apprenticeship in medicine with Dr. Jonathan Brown of Tewksbury, who was a relative of Theodore Parker’s first wife. Dr. Brown was very involved in treating the inhabitants of the Tewksbury Alms House (later Tewksbury State Hospital). Moses frequently accompanied him on his rounds there which instilled in Moses a life-long interest in that facility and in providing care for the poor in general.

Moses received further medical training at Long Island College Hospital in Brooklyn, New York in 1863, and at Harvard Medical School in 1863-64.

Because of the great demand for doctors in the Union Army, the course of study at Harvard was accelerated so that students graduated in March 1864. Moses immediately enlisted as the surgeon of the 57th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment which was being organized in Worcester. Shortly after joining that unit, but before his uniforms were even received from the tailor, Parker was summoned to Fortress Monroe, Virginia, by Lieutenant General Benjamin Butler, then commanding an army about to move towards Richmond. Butler had telegraphed the Massachusetts military authorities to immediately send to him “three competent surgeons” for his rapidly growing army, specifically naming Dr. Parker in his request.

When Parker arrived in Virginia in April 1864, he was assigned to the 2nd US Colored Cavalry Regiment as Assistant Surgeon. That unit soon moved into the trenches north of Petersburg, which was being placed under siege by General Grant and the Army of the Potomac.

Unlike earlier battles of the Civil War that involved linear tactics and relatively brief, though extremely deadly, confrontations, the siege of Petersburg resembled trench warfare on the Western Front in World War One. It was a long, miserable and very deadly stalemate. Throughout the campaign, Parker was frequently in the trenches and under fire as he cared for the men of his unit.

When the 18th Corps, the unit to which the 2nd Cavalry was assigned, left Fortress Monroe at the end of April 1864, it numbered 32,000 men. By July of that year, enemy fire and disease had reduced the number of troops in the line to 15,000. Looking towards the winter, Union commanders realized that without proper and adequate hospital facilities nearby, the Union death toll would grow much higher.

In July, 1864, Parker was detached from his unit and was ordered to construct a hospital to care for the troops during the coming winter. He chose a place called Point of Rocks on a high bluff overlooking the Appomattox River, 6 miles from Petersburg. Using local timber, Parker and his men constructed 20 “wards” each 250 feet long by 30 feet wide with a total capacity of 3500 beds. Once the hospital opened, it had many prominent visitors including Generals Grant and Butler, who were followed by President and Mrs. Lincoln. Parker described Lincoln as “kind and genial, but he seemed anxious and careworn, and was carelessly dressed.”

Grant kept up the pressure on Petersburg through the winter and spring. Confederate General Robert E. Lee, facing starvation and dwindling munitions for his army, ordered a breakout from the Petersburg siege at the beginning of April, 1864. Lee led his army westward in the hope of linking up with other Confederate Armies. However, Lee could not escape and soon surrendered to Grant at Appomattox.

With Petersburg having fallen, all remaining Rebel forces in nearby Richmond abandoned the Confederate capital. Because the Union Army had set off in pursuit of Lee, there was no immediate effort to occupy Richmond. Instead, small units and individual officers ventured into the city to look around. One of these visitors was Moses Greeley Parker who rode into the city on horseback. Another visitor was President Lincoln.

Still nearby as a spectator to the Union effort, Lincoln ordered his small naval gunboat to sail up the James River and dock at Richmond. Once ashore, Lincoln, his son Tad, and a small security detachment of sailors made their way to the Confederate White House, recently abandoned by Jefferson Davis. There, Lincoln encountered Parker and a number of other Union officers. Lincoln sat briefly at the desk of Davis, drank water from a pitcher, and soon departed. Parker also left soon thereafter, taking with him an ink well as a souvenir of his visit.

Despite its slow start, the Union Army soon occupied Richmond. On April 7, 1865, President Lincoln hosted an officer’s reception at the Confederate White House which Parker attended. According to Parker, Lincoln told him “the war is nearly over.” Parker also observed that in contrast to his appearance just a week earlier, Lincoln now looked as if a great load had been lifted off his shoulders.

Seven days later, Lincoln was dead, assassinated by John Wilkes Booth.

Moses Greeley Parker was discharged from the Union Army on May 24, 1865 and returned to the family home in Dracut. There, he spent months reading, relaxing, and restoring his health. However, his father died on December 23, 1865, which motivated Parker to open a medical practice to help support his mother and sister. In May 1866, he bought a house at 11 First Street in Lowell and spent the rest of his life there. (The VFW Highway/Route 110 heading towards Methuen now sits in place of First Street; Parker’s home was just three down from the Bridge Street bridge, with the rear of Parker’s lot overlooking the Merrimack River, across from Massachusetts Mills).

Parker opened a general practice of medicine and joined a highly respected medical community in Lowell. In November 1866, when the Sisters of Charity opened St. John’s Hospital, Parker provided treatment to patients, often at no charge. He also provided care to patients at the Tewksbury Almshouse. By 1873, Parker had decided to specialize in ophthalmology and spent a year studying that field in Vienna, Austria.

From an early age, Parker had exhibited a curiosity about scientific matters, so it should be no surprise that in April, 1876, he attended a demonstration of a new technology at Lowell’s Huntington Hall. The person giving the demonstration was Alexander Graham Bell and the technology he was demonstrating was the telephone. Parker immediately saw the potential of the new device, and soon purchased two wooden phones from Bell; one for his home, the other for his office. This was before switchboards, so phones only communicated from point to point and not on a wide network. Parker’s was the first private telephone line outside of Boston.

Parker’s interest in the telephone grew. On March 1, 1880, he purchased 10 shares of stock in the fledgling Lowell District Telephone Company, although he reportedly asked the company’s treasurer, Charles Glidden, to keep his stock purchase a secret lest he be seen by his neighbors as “flighty and unreliable” for investing in the phone.

Parker continued to invest in phone company stock, especially after the Lowell exchange merged with New England Telephone and Telegraph. In 1886, he became a director of New England Telephone and Telegraph and began working two days each week at the company’s Boston headquarters. Bell was also instrumental in the creation of the modern telephone book and in its printing by Lowell’s Courier Citizen Corporation.

But Parker’s most important contribution to the telephone industry came in the late 1870s. By then there was a central telephone exchange that was staffed by four women operators who had memorized which lines belonged to which customers. When a measles epidemic struck the city, Parker worried that if these four women got sick, the phone system would shut down. He thought that replacement operators could be more easily trained if the phone lines were numbered. He suggested this to Alexander Graham Bell who liked the idea, and adopted it for the entire New England Tel & Tel system. This made Moses Greeley Parker the inventor of the phone number.

As his involvement in the phone company grew, Parker reduced the time he spent on medical matters. However, for his entire life he had been interested in history and historical artifacts, and much of his time in his later years was devoted to such things. For example, he was active in several historical and patriotic organizations such as the Lowell Historical Society, and was once the national commander of the Sons of the American Revolution (two great grandfathers fought against the British on April 19, 1775). Parker also had a great interest in genealogy. In his will, he directed his executors to hire a “competent person” to write his posthumous biography.

Shortly after the turn of the new century when he had just turned 60 years old, Moses Greeley Parker found himself growing easily fatigued. His self-diagnosis was heart disease. It grew increasingly problematic for him and he died on October 1, 1917. He was buried in Lowell Cemetery.

Moses Greeley Parker never married and had no children. His sister, Mrs. Leonard H. Morrison, and his nephew Theodore Edson Greeley Parker (son of Moses’ half-brother) survived him and inherited his great wealth. In keeping with the wish of Moses, they used this wealth for philanthropic causes including the endowment of the Moses Greeley Parker lecture series, funding the town of Dracut library, and creating the Theodore Edson Parker Foundation, set up by Moses’s nephew with money left to him by Moses. The Parker Foundation has funded countless charitable and civic endeavors in Greater Lowell.