“The Wamesit Trail of Tears” by Jay Gaffney

THE WAMESIT TRAIL OF TEARS: A Story of the life, trials, and FINAL exodus of our Wamesit and Pawtucket neighbors

By Jay Gaffney

“he buys the Indian’s moccasins and baskets, then buys his hunting grounds, and at length forgets where he is buried and plows up his bones”

Henry David Thoreau – A week on the Concord and Merrimac

DEDICATION

Mico Kaufman: World War II Concentration Camp Survivor, Sculptor to Presidents, Whistler Museum Distinguished Artist, Author, UMass Lowell, Doctor of Humane Letters

His powerful sculptures combine art and history to help us see our heritage all around us.

IN MEMORIAM DEDICATIONS

Francis L. “Taddy” Brown: 1915 -2001, WWII Army Veteran, Town Highway Foreman, Tewksbury Town Historian

Eugene Winter: 1927- 2014, Educator, US Army Veteran, Archaeologist, Curator, Director Tewksbury Historical Society, President Lowell Historical Society

So Many times writing this article, I found myself wishing I could talk to Gene and Taddy. It would have been a much better article

Copyright: James J. Gaffney III 2016 – All Rights Reserved.

Photography: Chloe Paige Morrissey 2015

Enter the main gate to Lowell’s Edson Cemetery. Look to your right, you’ll see “The Improved Order of the Red Man” (The Improved Order of the Red Men is a fraternal organization which traces its origin back to the Sons of Liberty1) statue of Passaconaway, “Child of the Bear” – one of the mightiest Sachems (“Chiefs”) of the Algonquin Totem of the Wolf nation. When the white man arrived, The Algonquin realm covered New England and other parts of the early American Northeast. You will be looking up – making the statue seem larger than life – like the mighty Chief it portrays. A “physical giant,” 2 he was the self proclaimed strongest bow man 3 of his tribes and a legendary Pow Wow (“Pow Wows” translated as “Dreamers) Pow Wows were a form of priest believed to possess supernatural powers. Reflecting the English viewpoint, Daniel Gookin described them as combination physician and witch. 4APassaconaway could make rocks dance, engulf himself in flames, and dive into a broad stretch of the Merrimack remaining unseen until emerging from a mist to hail watchers from the opposite shore. Some said he could fly.5

Passaconaway Statue, Edson Cemetery, Lowell, Mass

Passaconaway’s Pennacook Federation extended from the sea to mountains and from the Penobscot River to the Merrimack. Besides his core Penacook tribe, his federation listed eleven other tribes, including the Greater Lowell area Pawtuckets and Wamesits, assembled from tribes which had been decimated by Mohawk raids, wars with Northern Tarratines, and a succession of early seventeenth century epidemics which wiped out entire villages, sometimes leaving heaps of unburied bodies. Despite the toll of these disasters, the Passaconaway of the statue held sway over 3- 4,000 Indians and could put 4- 500 hundred battle ready warriors in the field.6 He maintained residences at Pennacook, Piscataqua, and near the Pawtucket Falls where the southernmost part of the Merrimack turns Northeast to head for the sea. Passaconaway was a Bashaba, somewhat equivalent to an emperor, over multiple sachems or chiefs.7 Like European emperors,he used war, diplomacy, and marriage to consolidate his power. 8 but his rule was also based on consensus. The Sachems (tribal chiefs) acted as counselors 9and had a voice in Federation affairs which could be raised at annual town meeting style councils.10 The Pawtucket Falls area was the site of one of the Pawtucket tribe’s villages and the best fishing on the Merrimack. 11The Pawtucket domain extended along the Merrimack North to Concord and East to Haverhill. 12When English settlement began to flow into the Greater Lowell area, the Pawtuckets controlled, besides the Falls area, what is now Tyngsboro, Dracut, Dunstable, and Pawtucketville. Their capital was thought to be in Dracut. 13The area East of the falls and South of the river was home to the Wamesits, centered where the Concord River emptied into the Merrimack and extending into Tewksbury, Belvedere, and the rest of Lowell East of the Falls. The Wamesits also had a Western branch in Marlborough. 14 Marlborough Historian Paul Brodeur believes that the Concord Assabet Riverway network access, and possibly intermarriage, may have led Wamesits out to this satellite village. 15Tribal names and identities were confusing and

there was some overlap or interchangeability in the use of the Pawtucket and Wamesit terms. Wamesits and Pawtuckets were listed separately in the early history enumerations of the Pennacook Federation tribes. As early as 1637 Thomas Morton listed then as separate tribes in New English Canaan 16, as did Daniel Gookin and other early historians. However, some histories considered them one tribe sometimes distinguished by their main place names. Pennacook tribal formations were often more geographic groupings than separate peoples, and tribal names were often place based, Wamesit translating as fishing place or place of large assembly and Pawtucket as place of large noises or sometimes falling water. The overlap was even more pronounced on the South side of the river because of the proximity and intermingling of the two groups. 17They did not differ in language or culture. Tribes such as the Wamesits and Pawtuckets were some times also indentified with name of the parent Pennacook Federation. 17AThe Falls area was also a major Pennacook Federation site for the “town Meeting” councils 20 and festivals as well as fishing.

Passaconnaway’s power and stature was equal to the famous Pokanaket Chief Massasoit. The two Algonquin sovereigns watched together from a concealed location when the English came ashore in 1620. Massasoit and Passaconaway both embarked on a policy of friendly relations with their new neighbors, providing helpful hints on planting, food sources, and other survival information which helped carry the settlers through their early years. Passaconaway’s friendship policy toward his new neighbors, like Massasoit’s to the South, was complicated by the threat posed by other Indians. Massasoit had been forced to submit to the more numerous Rhode Island/Southeastern Massachusetts Narragansetts who had escaped the full brunt of the plague. 21 Passaconaway’s main threat was marauding Mohawks sweeping down from New York. The Algonquins of Massasoit and Passaconaway hunted the woods and fished the streams, but they lived in villages, sometimes laid out with streets, and sometimes even protected by forts. Much of their sustenance came from husbandry, especially raising corn. 22The Iroquois Mohawks were the Viking raiders of native America – splitting into small groups to avoid detection and reassembling at predetermined locations to strike unsuspecting targets before disappearing with their scalps and plunder. 23 Algonquin fear of them is suggested by the name Mohawk itself, Algonquin for Cannibal. 24 Gookin wrote that four or five Mohawks could send Indians fleeing to villages and forts. 25 Passaconaway’s preoccupation with the Mohawk threat led him to hazard something which never ended well for the Indians – a land deal with the English. The 1629 Wheelwright deed ceded much of his New Hampshire and possibly some of his Massachusetts territory to the English. The purchase consideration was one coat a year. 26 The Mohawk defense theory behind opening this land to English settlement may have been based on giving the English a “we’re all in this together” stake in helping turn back the raids. 27 He may have thought, as did many Indians, that he was deeding a right to use the land in common with his own people, 27A but the sale started a cycle of dispossession which displaced him from most of his New Hampshire land- even his favorite Naticook Island refuge Northeast of Merrimac. Just a few years after his retirement in 1660, the once mighty, but now nearly destitute, Passaconaway was forced to petition the General Court for a few acres where he could live out his life. 28 They granted him 3000 acres of land in Litchfield, New Hampshire He was seen by Gookin in 1663 believed to be then 120 years old. 29 The plaque on the base of the Edson statue says he lived to 122 and also identifies him as “Aspenquid the Indian Saint” based on his good works among the people living around Mt. Agamenticus. There is another legend of his ascension to the Diving Council Fire in a flaming sled. 30

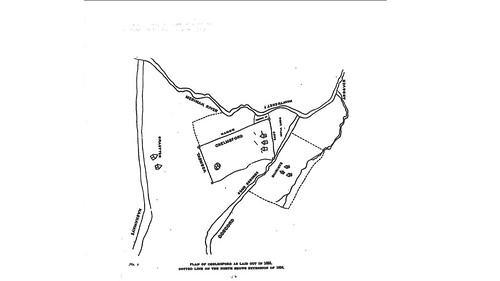

Down south in what is now Lowell and Tewksbury the tide of encroaching settlement rolled in more slowly. When it reached the Lowell area, the resident Pawtuckets and Wamesits had a friend in Court: Reverend John Eliot was carrying out the 1644 Massachusetts legislative mandate of bringing the Gospel to the Indians. 31 Eliot delivered his first sermon to Natick Indians in 1646 and was preaching in Lowell a year later. The Wamesits and Pawtuckets were receptive to Eliot’s preaching and he established the fifth of his fourteen Praying Towns in Wamesit territory in 1653. 32 The praying town, sometimes called Pentucket, was in existence when settlers from Woburn and Concord petitioned the General Court for parts of what is now Chelmsford and Lowell. Eliot responded with a defensive counter petition protecting the interest of the Indians. The Chelmsford grant was part of the concurrent 1655 incorporation of Chelmsford, Billerica, and Groton and is shown as the six-mile square rectangle shown on the 1653 Plan attached. The Indians kept the Triangle formed by the Merrimack and Concord Rivers along with land running west along the Merrimack. The original Chelmsford grant had no Merrimack frontage. A year later, Chelmsford was back looking for more. It got joint ownership of the land along the river except for John Sagamore’s planting ground – now Middlesex village -which Eliot managed to carve out for the Indians. In 1660 Chelmsford got most of the joint land in exchange for a smaller parcel deeded to the Indians. There was one more boundary adjustment in 1665 which settled Chelmsford’s Eastern boundary along what is now Baldwin Street and roughly following the old Middlesex Canal path in the Lowell Highlands. The Planting ground and expansion are shown by the dotted lines on The Plan. 33 After the boundaries stabilized, the Indians on the South and West of the river retained about 2500 Acres, 1500 in Chelmsford Lowell and another 1000 in Tewksbury. 34The area was set off by the “Indian Ditch” and a landmark known as the “Wamesit Stake” which marked the boundary junction of Billerica, Chelmsford and the area reserved for the Indians. 35 The stake and traces of the ditch were reported still visible at end of 19thcentury. 36

“The Plan”

The 1665 adjustment also returned Wickasauke (now Tyng) island to the Indians. Wannalancit, Passaconaway’s son and successor was forced to pawn it to get his older brother out of jail. Nanamocommuck’s confinement resulted from standing as surety for the debt of another Indian, who may have been a victim of some colonial predatory lending. Nanamocommuck cosigned a note to John Tinker. Joseph Price Moore III wrote that Tinker had a “vile reputation for selling illicit guns and alcohol” surmising that the debt may come from alcohol purchases. 37A In1665, Wannalancit and two others, describing themselves as “poore neibor Indians”, petitioned for the return of Wickasauke. They got it back but gave up 500 Dracut acres in the exchange with then current owner Captain John Evered alias Webb who bought it from Tinker. 38 Passaconaway had daughters. One of them, Weetamo, married and later left the Chief of the Saugus tribe. She became part of the legend in John Greenleaf Whittier’s Bride of Pennacook.

The small Wamesit village had a civic structure. Civil administration was overseen by local Sachem, Numphow, a Passaconnaway son in law. 39A He teamed with a Harvard Indian College graduate named Samuel, designated the “Teacher” who handled religious instruction. The Wamesits’ existing belief in the immortality of the soul and resurrection 40 made some of them receptive hearers of the word preached by Eliot and his Indian Deacons, and his preaching attracted crowds from beyond the local villages. In 1656, Daniel Gookin, was appointed Superintendent of all Indians who had submitted to English jurisdiction. 41 The General Court had established monthly court sessions for the Praying Villages, (actual sessions were less frequent) 42 and Gookin was, effectively, the chief magistrate for the praying villages. He often accompanied Eliot’s visits. John Pendergast wrote of Wamesit settlements near what is now the Auditorium, Boott Mills, and Lowell General Hospital’s Saints Campus. 43 Gookin estimated 250 Wamesits and Pawtuckets living in Lowell and Western Tewksbury. 44(Gookin’s estimate may have applied just to men making the total population larger. 44A) The population of the praying town itself was estimated at 75. 45 Wilson Water’s History of Chelmsford located the “Court” log cabin near Boott Mill and the Chapel at the West end of Appleton Street. 46 Waters reported that Cowley “was certain” of the Chapel location at the site of the present Eliot Church, 47 although it didn’t show up in Cowley’s book. On the villages’ civil administration side, Gookin and Numphow maintained a court house near the Boott Mill and a constable office in Belvedere. The Wamesit capital was also in Belvedere. 48 Across the River, court and religious sessions were held at the Coburn House near Ferry Lane – later a war time Garrison house. 49 Samuel the teacher, who was sent to school by the Corporation for the Indians, could read and write English, 50 and there is evidence of reading and writing among other Indians. Many communications between the English and Indians were written.

The power of the word preached by Eliot and Samuel went right to the top. Passaconaway was reluctant to hear it at first and resisted contact with Eliot and Gookin – even expressing fear that the English might kill him. 51 He had his reasons. In 1642, acting on a rumor of collaboration with hostile Pequots, the English sent a force of 100 armed men out to bring him in. Passsaconaway escaped when the English posse was delayed by a storm, but Wannalancit was not so lucky. He was surprised in his wigwam, shot at, and, marched into Boston with a rope around his neck – his wife and children also in tow. After demanding and getting their release, Passaconaway accepted a face saving apology, 52 and shortly afterward acquiesced to the terms of an onerous treaty aptly called Articles of “Submission” which made them surrender their guns and a follow on 1645 treaty which put further restraints on them and also required them to be informers, reporting any hostile or suspicious activity. 53 The English also extracted consent for the sale of Haverhill to its inhabitants. 54 This treatment was likely weighing on his mind when he refused a 1647 invitation to meet with Eliot, but a year later, he relented and promised to “consider” Eliot’s message, soon becoming an ally in promoting it. In 1648 he promised Eliot that he would pray to God and persuade all his sons to do the same. 55 He even tried to get Eliot to buy into a more exclusive relationship with the Pennacooks and shift his efforts nearer Concord – arguing that the message needed more consistent reinforcement than Eliot’s sporadic visits spread among his fourteen village circuit could provide. 56 His son, Wannalancit, who succeeded him as Chief, became equally devout. Wannalancit wrestled with a formal conversion commitment knowing that it would be resented by other Indians, especially the Pow Wows, whose authority would be undermined. In 1674 he finally committed, announcing that his spiritual journey would now continue in a “New Canoe.” He walked two miles to services from his wigwam near the Franco American School on 357 Pawtucket Street. 58 Passaconaway had a wigwam across the river near the Congregational Church. 59 The “New Canoe” speech was one of those events where the dividing lines between eras overlap. While Wannalancit was adopting his new faith, over on what is now Wood Street, English settlers were constructing the Bowers House, the oldest building still standing in Lowell.

Rev. John Eliot preaching to the Indians. Clipart courtesy of FCIT

The stabilization of the boundaries was accompanied by an interlude of peace with their Chelmsford neighbors. Commercial relations developed. In 1657, the Council of Assistants (“Council”) (the upper house of the General Court sometimes called the “Magistrates) gave the exclusive Merrimack River area trading rights to Wheeler, Simon Willard and Thomas Henchman. 60 Some of the Wamesits and Pawtucket’s hired out to local farmers. The villages on the south side of the river merged, either in the course of the Chelmsford boundary transaction or, possibly later, after the Algonquin’s costly 1669 multi tribe preemptive invasion of Mohawk territory in New York – and at about the same time that Wannalancit constructed the palisaded fort on the high ground at Fort Hill Park. 61 Built as a refuge from Mohawk raids, it may have been one of Wannalancit’s residences, and was reported used as a signaling station for messaging to other high points in Chelmsford. 62 The merger was an absorption of the Pawtucket village into the Wamesit 63 which became the seat and capital. The name “Wamesit” eventually superseded “the Indian Town of Pawtucket” which had been used in reference to settlements South of the river as early 1642. 65 The change may have actually been a return the original. 65AWhen the largest part of Greater Lowell Indian land was sold off in 1686, the transaction was known as the “Wamesit Purchase.” 66 The Courier Citizen used the Pawtucket and Wamesit terms as interchangeable, 67 and there were many instances where the reference to one included at least some of the others – especially as it applies to the settlements on the south side of the river.(this overlap probably applies to many of the references in this article as well. The same interchangeability and overlap also applies in some cases to the uses of Chelmsford and Lowell, especially before they were separated) The course of coexistence in effect when Wannalancit embarked in his “new canoe” was charted by Passaconaway almost from the time he and Massasoit watched the first pilgrims wade ashore at Plymouth.

1660 saw a major changing of the guard in the Algonquin hierarchy. Massasoit died passing his tribal leadership to son, Wamsutta, or Alexander, and Passaconaway made his famous retirement speech at the Pawtucket Falls festival site. Passaconaway charged his people to “bend before the wind” and continue to accommodate themselves to peace with the English – not because treatment by the English had earned their friendship but because he saw futility in any other course. He related his unsuccessful efforts to use his full Pow Wow arsenal of sorcery to destroy or drive them off. He tried to infect them with disease and burn their ships. 68 Echoing his adopted Christian theology he related how the “Great White Father” had whispered “Peace, Peace, you are powerless against them”. 69 He saw peace as his peoples’ only hope for survival even if one which would be compromised. He may have felt forewarned by English massacre of the Connecticut Pequot tribe forces in 1637. 70 The speech was Passaconway’s last official act and the last major multitribe gathering at the Falls. Further South, while Passaconaway and Wannalacit made their bargain with the realities on the ground, accepting “such terms as destiny offered”, 70A the Pokanaket Chief Metacomet, known as King Philip, who succeeded his deceased older brother, plotted a very different course. Philip chafed under grievances including shrinking territory and the heavy hand of English jurisdiction which often treated the Indians as subjects more than sovereign people. The historian Drake thought that treatment of Indians as inferiors was as big a cause of war as the encroachment on their lands.71 Philip’s course was a desperate all or nothing war to save their way of life “even if it were against fate itself.” 72

When war broke out, both sides rushed to secure alliances and neutralize potential enemies, Wannalancit immediately declared for his father’s path of peace, but found neutrality to be an exposed position. He was getting pressure, including threats, from both sides. The war accelerated the break-up of Wannalancit’s federation. Passaconaway’s oldest son, Nanamocommuck, Chief of the Wachusett tribe, never liked the English, especially after his stay in one of their jails. He died soon after his release.73 The leadership then passed to Wannalancit. Some of Nanamocommuck’s aversion to the English must have rubbed off on his son Kangamangus (a.k.a John Hawkins) The hostility was aggravated by the New Canoe conversion and contributed to Kangamangus’ seceding from the federation and taking Northern White Mountain area Pennacooks with him. 74 Wannalancit saw a self-imposed exile as the only way out.- the only way to avoid being drawn into the conflict and stay under the radar of the English, presuming that they would be ”highly provoked against all Indians.” He headed north to the Pennacook area accompanied by something less than a hundred followers. Wannalancit’s group included some of his relatives, 75 and would likely have drawn from the Wamesit village as well as locations across the river. 76 The Indians in the praying village, along with some other area Wamesits and Pawtuckets stayed put – but not for long.

The “Trail of Tears” was the name given by Cherokees to the hardships endured on their Journey to western “Indian Lands” after the 1830 “Indian Removal Act evicted them from their Georgia home. The outbreak of King Philip’s War would soon send Wamesits (and Pawtuckets) on their own “Trail of Tears.” In West Tewksbury’s Wamesit Park, along Route 38 in the Eastern part of territory once ruled by the Wamesits, is Mico Kaufman’s majestic landmark statue of the “Wamesit Indian.” There is a contrast with Passaconaway’s statue in the cemetery. Passaconaway, looks forward in a posture of confident command holding a weapon in each hand. The Wamesit Indian holds a fishing spear, probably standing on a bank of the Merrimack, Concord or possibly Shawsheen River. His glance is downward; Is he just intent on his catch – or is he hearing the rumors of war which will uproot the Wamesits and turn them out on their “trail of tears” – journeys of hard travelling which would keep kept them moving like nomads south to Boston and back and forth to New Hampshire going North as far as the Connecticut river headwaters, suffering from hunger, exposure, and violence along the way, and finally leaving New England and America all together.

The “Wamesit Indian.” Wamesit Park, Rte 38, Tewksbury. Sculpture by Mico Kaufman

The General Court – nervous about Wannalancit’s departure and what he was up to- and hoping to use him as a peace broker, initiated plans to get him back. The Court ordered military commander Daniel Hinchman to send up some reliable Indian messengers, including Numphow with safe conduct promises, but Wannalancit withdrew from these contact attempts and retreated further into the woods. The English may have had an exaggerated sense of his force and suspected hostile motives for this withdrawal. 77 They sent Captain Robert Mosely and 100 armed men on another search. 78 The histories vary as to whether he was sent North to “dispel the danger,”79 and disperse the Indian enemy, 80 or even to bring him back by force 81-or on a more benign mission to “ascertain the position of Wannalancit in regard to the war.” 82 If the mission had a diplomatic component, Mosely was the worst possible choice for the job. Mosely commanded a seventeenth century “Dirty Dozen” kind of paramilitary unit which included pirates and other misfits released from jail for war service. 83 He was one of the Colony’s most effective but also ruthless commanders, He seethed with an undiscriminating hatred of all Indians. Mosely took his orders as a license to torch the wigwams and destroy the food supplies he found at Wannalancit’s just deserted village Wannalancit was alerted to their approach and might have had the tactical advantage if he had followed the urging of some of his braves to resist. 84 Instead, he headed further north up to the Connecticut River headwaters near the most northern part of the New Hampshire Vermont border. Mosely’s rampage was either “not approved” or may have resulted in second thoughts, and apologies followed. 85 Mosely’s overkill was an early example of the indiscriminate treatment of Indians which Wannalancit feared would follow the outbreak of hostilities –treatment which materialized soon enough in both official policy as well as in officially unsanctioned but often unpunished acts of some of its citizens. As described in the Illustrated History of Lowell and vicinity “Popular sentiment made no distinction between the friendly and hostile Indians but regarded them one and all as an enemy to the public peace, a foe to be treated with warlike severity.”86 It was also an example of Wannalancit’s determination, often severely tested, to refrain from retaliating in the face of provocation.

English policy toward the natives, who were there first, officially recognized the tribes as sovereign nations, but in practice treated them as subjects. The English, “following their course of settlement with small regard for the rights of natives,”87 imposed laws restricting guns, horses, boats, land and liquor sales. 88 The English assumed the right to approve appointment of village rulers. Even Laws designed for their own good were patronizing and tended to have loop holes which could be exploited by the connected or were otherwise ignored. Alcohol sales were outlawed or restricted 89 but continued as a major trade staple. Like the Prohibition Era, the laws did little to reduce the flow of Alcohol. According to Gookin, “yet some ill disposed people, for filthy lucre’s sake, do sell to the Indians secretly.” 90 (did he have Tinker in mind?)These traders likely contributed to alcohol use which Richard W. Cogley wrote was “known to be a problem in several pre war settlements-Wamesit, Pantucket , Hassanamessit—-.” 91 The effects of alcohol on the Indians become a stereotype which fed into local prejudice, usually ignoring the English settlers’ own role in introducing the natives to what Gookin called the “beastly sin of Drunkenness” and violating their own laws to maintain this contraband traffic. 92 Indians complained about liquor sales. It was on King Philip’s list of grievances which he presented to Rhode Island Governor John Easton in eleventh hour mediation efforts to stave off the war. Philip complained that the English “made them drunk and cheated them in bargains.” 93

Once war broke out in June of 1675, more restrictions were piled on. Policy often bent with the wind of a public opinion increasingly charged with fear and hostility as all Indians, including the peaceful ones, were seen as a threat by many settlers. On August 30th, the General Court shut down the use of allied Praying Indian companies, including the Wamesit Company, 96 in spite of their proving themselves in one in one of the first major battles. They confined Indians to their villages – a virtual house arrest which effectively established a “free fire zone” one mile outside. The grim Council order prescribed “extermination” 97 as the penalty for violation. The Lowell area Indians were granted a harvest time exception to bring in their crops, if overseen by their rulers, Numphow and John Aline. 98

As the arc of the war, which started in the Southeast, swung around to the West and then hooked back east, the Wamesits were finding the path of peace more like a gauntlet- subjecting them to attacks form both sides. King Philip’s supporters killed some of them as suspected informers. 99 Chelmsford escaped major attacks but was victimized by guerilla type hit and run attacks. (Chelmsford did suffer losses outside the town. Chelmsford soldiers were part of the Brookfield ambush and siege where half the English force were casualties. Edward Colburn was killed and John Waldo wounded. 100) On October 18th, 1675, Lieutenant James Richardson’s haystack was set on fire. Richardson himself did not blame the local Indians, but the next day, the General Court ordered the whole tribe of 145 haled into Boston. The court released the women and children leaving 33 able bodied men to face their first encounter with English Justice. 101 A wholesale guilty verdict was lodged against all 33 by the General Court Deputies –today’s state representatives. They were partly rescued by the Magistrates who overturned the verdict but still allowed three of them to be sold into slavery despite Eliot’s appeals. 102 Their return trip to Lowell took them through Woburn where a crowd gathered and harassed them – a shot was fired killing one of the Wamesits. The English were scrupulous about observing at least the formalities of justice and brought the shooter to trial, but the jury bought an “I didn’t know the gun was loaded” type accident excuse. 103 The jury stood by their verdict despite judge’s instructions to reconsider. 104 The incident was not exactly a precedent but was part of a repeated pattern where justice for Indians was denied because juries wouldn’t convict their white friends and neighbors. On October 30th, the General court sent some 200 Natick Indians to a duration of the war confinement on Boston Harbor’s Deer Island – reminiscent of the WWII internment of the Nisei Japanese Americans. The same fear and prejudice which consigned the Naticks to a winter of scarce food and icy harbor winds may have actually saved the Wamesits and Pawtuckets from a similar fate. In early December, the Council ordered Henchman to try to persuade the Chelmsford Indians to join the Naticks at Deer Island. Another plan called for their removal to Noddle’s Island – (now part of Logan airport) a plan blocked by the Not in My Back Yard opposition of local residents. 105 Their respite was short-lived. On November 15th, arson struck the Richardson property again. A barn full of hay and corn was set afire. The Wamesit village became a victim of seventeenth century vigilante justice. A group described by Cowley as a”scoundrel mob” “took the law into their own hands” and showed up at the village calling the Indians out of their wigwams. Two of the gang fired their guns, wounding five and killing the young grandson of Sagamore John. 106 The Boy’s mother, Sarah Onamog, was the leader of a group of Marlborough Wamesits who had reunited with their “primary tribe”107 in Lowell after their Okommakamesit Praying Village, established in 1654, 107A was broken up. (Reporting back on his unsuccessful effort to contact Wannalancit, Numphow advised the Governor that Groton Indians living in Pennacook also wanted to come to Lowell. 108) Mosely was a culprit in Marlborough too. Several Lancaster settlers had been killed in an Indian raid, and Mosely went on the hunt for the perpetrators. Mosely’s interrogation technique featured extracting confessions by threatening to shoot the suspect. 109 In this case, a terrified Indian, looking into the barrel of Mosely’s gun pointed the finger at some Nipmuc refugees living among the Marlborough Wamesit. 110 Foreshadowing events in Chelmsford/Lowell several months later, Mosely marched the suspects into Boston. Like the later Wamesit suspects, they were all acquitted, 111 but the finding of innocence failed to cool off the anti Indian hysteria and the townspeople banned all Indians from Marlborough, ending the village’s existence. 112When the second Chelmsford matter came to trial, defendants Lorgin and Robbins were acquitted because of “insufficient evidence,”113 The Indians’ confidence in the protection of English justice was now gone.

Many of the Wamesits fled north hoping to catch up with Wannalacncit who had withdrawn even further north. The group heading North was joined by Sarah Onamog and the Marlborough affiliates. Attempts to contact Wannalancit only pushed him still further out of their range. The Council ordered Henchman to persuade them to turn around – in part from fear that they might Join King Phillip. Numphow and John Aline replied by messenger acknowledging help from the Council but fearing that “many English be not good and maybe they come to us and kill us as in the other case”. The message also noted that “—when there was any harm done in Chelmsford, they laid it to us” The letter concluded with regrets about missing prayers with their teacher and remembering their love to Henchman and Richardson. 114 The accusations suggested success of tactics employed by what Gookin described as the “Skulking” kind of Indian who harassed villages hoping to provoke retaliation which would drive the Wamesit and other friendly Indians into the hostile camp. 115 The tactics also played into the existing fear and prejudice along with good old fashioned greed of some who were hoping to see the Indians driven off their land. At wars end, Indians named Nathaniel and John Monaco (“One eyed John) confessed to burnings which were part of this strategy. 116 Hunger and cold finally accomplished what diplomacy couldn’t, and most of the Wamesits abandoned their quest after a 23 day trek through the woods. 117 During the trek, these pilgrims persevered in their faith keeping 3 Sabbaths and reciting Psalms 35, 46, and 118. (all three Psalms looked to God’s help in time of trial Psalm 35“Stop the way against them that persecute me”; Psalm 46 “the God of Jacob is our refuge” Psalm 118 “I called up the lord in distress.) 118 As winter came on, Wannalancit and the band with him, perhaps a hundred, began a hard winter with short food supplies around the headwaters of the Connecticut river while the returning Wamesits settled back in at Lowell. The Council sent a delegation consisting of Gookin, Eliot and Major Willard to reassure them and try to improve relations with their Chelmsford neighbors. 119 They also sent a delegation to retrieve Sarah Onamog and her Marlborough group which lingered in the Concord area. 120 Any sense of security achieved by these efforts was short-lived. A Christmas day house burning probably revived fears of further retribution. There were continued burnings and sighting of hostile Indians. 121 Joseph Parker and his son were ambushed by a group of Indians, the son taking a bullet through the arm. 122The Wamesits faced a further threat; King Philip’s forces, always on the move were running out of food and were plundering the stores of friendly Indians. The Council was getting pleas for help from both Indian and English residents, but facing a common enemy did little to improve Chelmsford settlers’ relations with their Wamesit neighbors. The Wamesits just couldn’t win. After they left Groton settlers complained about their “suspicious removal.” 123 After their return, the English complained to the Council about the threat posed to their “lives and estates” by reason of their “return.”124

The prejudice against the Indians even extended to threats against English allies such as Gookin and Eliot and others seen as close to them. 125 The settlers saw the war as a judgement of God. Gookin saw the war as God’s dual purpose punishment of both the English and the Indians by use of the “heathen” to “chastise and punish the English for their sins” and bring down simultaneous “punishment and destruction of the heathens” for their rejection of the Gospel offered to them. Gookin ordered forces under his command to “be executioners of His (God’s} just indignation.” 126 Even supporters of (at least friendly Indians) like Gookin disparaged some of the Indian cultural features which didn’t match up with theirs – especially their emerging Protestant capitalism. Gookin criticized their lack of industry and specifically their lack of initiative in failing to commercialize Merrimack River fishing. 127 Eliot’s Christian love for the Indians was not shared by all English clergy. After the Pequot Massacre, Cotton Mather declared “5 or 600 of these barbarians were dismissed from a world which was burdened by them.” 128 Prejudice was not limited to Indians but included dissidents such as Quakers. Drake reports of Quakers being forced to run the gauntlet for “refusal to go out on command” referring to military service. 129 Quaker meetings were also banned. 130 Catholics were another target. A 1647 Law banned Jesuits from entering the colony. Catholic as well as Anglican holidays were banned. 131Wamesits saw themselves in increasing peril from both English and marauding Indians.

When Wannalancit led his band north soon after the outbreak of war, his concern that the white settlers would be “provoked against all Indians” 132 proved prophetic for the Wamesits. The acts of hostile Indians had twice been laid at their doorstep and led to the shedding of innocent Wamesit blood. The prejudice of the jurors and deputies failed to punish the offenders. In the first Richardson arson, the Magistrates had to intervene to prevent a mass conviction of the Wamesits by the Deputies. Even then, three were transported into slavery over the objections of Eliot. Caught in the middle, they feared violence at the hands of the English, as well as Indians. They also caught some of the blame for the acts of those hostile Indians. They petitioned the Council to relocate them to some safer place, asking that the council to “pray consider our condition with speed.” The petition expressed their fear that “other Indians would come and do mischief and it would be imputed to them and they would be blamed for it.” The Council promised to respond but failed to act, (possibly too busy? )133 and most of the Wamesits headed North to join up with Wannalancit. There was no Geneva Convention during King Philip’s war. Both sides traded in scalps and there were a “thousand atrocities on both sides,” 134, but this second Wamesit exodus was followed by one of the war’s worst. Some Wamesits, too old or infirm to travel, were left behind. They were “roasted alive” in their tents set on fire by some locals. 135 This killing of helpless non combatants was not an isolated incident. The English forces committed several similar and larger scale massacres when they killed aged and infirm Indians unable to keep up with their fleeing Indian forces. In one case these Indians were burned in their tents like the sick and elderly Wamesits. 136 The aged and infirmed who perished in the inferno of their tents were not the only casualties of the Wamesit exodus. Several more Wamesits perished from exposure or famine on the journey north, including the Wamesit Sachem Numphow and the spiritual teacher Mystic George. 137 Cowley compared the hardships of this leg of their “Trail of Tears” to “The horrors of a French retreat from Moscow” 138

The Chelmsford Area continued to be hit with a pattern of harassing types of attacks, 139 without any indication that this evidence of continuing violence after they left did anything to exonerate the now departed Wamesits in the minds of the locals. Chelmsford itself had escaped major attack, but events in the neighborhood gave good reason for continued alarm. The front had moved east and was coming closer. Groton was burned to the ground on March 14th. Chelmsford directed desperate pleas for aid to the council. One February letter to the Governor and Council complained that their “garrisons were so weake and our men so scattered about their personal occasions: that we are without rational hope for want of men, and what is otherwise necessary. 140 The Middlesex Council proposed reinforcing the Chelmsford, Concord, and Sudbury Garrisons by forty men apiece. As part of supplying this build up, The English wasted no time in exploiting the Wamesit absence with plans to raise 1,000 bushels of corn on what was recently, and probably still legally, their land. 141 On April 25th,

Lieutenant Richardson and Captain Samuel Hunting were ordered to take a contingent assembled at Charleston, build a fort at Pawtucket, and then to patrol the area, and be ready as a reaction force to respond to Indian attack. 142 The makeup of the force reflected a change in war policy where tactical considerations overrode prejudice and Praying Indians were put back into the field. The Indian contingent consisted of Natick Indians getting a reprieve from Deer Island. The construction of the Fort at the falls ended up postponed so the force could be diverted to Sudbury then under heavy attack by Philips forces. Philip and his field commanders had mastered (invented?) the Vietnam War tactic of attacking a fixed installation and ambushing the relief force. After putting the town under siege, Philip managed to wipe out two of these relief columns coming from Concord and Marlbourough. 143 The Hunting Richardson force arrived in time to rescue survivors who found refuge in a Mill. They were also part of reinforcements now coming from several directions which forced King Philip to quit the field. Body counts were part of psychological warfare operations even back then, Philip claimed killing 74 English. The English claim of also inflicting heavy casualties is harder to substantiate given the tactical developments on the ground. The Lancaster captive Mary Rowlandson was with Philp’s forces and didn’t notice anyone missing from the ones she recognized. 144 Like the Nisei, Christian Indians wanted to demonstrate their loyalty through military service. They were credited with doing “good service” at Sudbury and several other engagements. Samuel Drake cited More in The Warre In New England Visibly Ended) “since the Indians have abated their fears of them and employed them in this warre, they have had most manifest proofs of their fidelity and valour.” 145 In the aftermath of reintroducing the service of praying and other friendly Indians in 1676, many believed that the war would have been shortened if their service wasn’t suspended after Mount Hope. 145A

Could the Wamesits have marched to those drums if their neighbors hadn’t driven them away? The Wamesits have been described as “peaceful” or “peace loving.” 146 They abided by Passaconaways’s mandate, continued in force by Wannalancit, to be peaceful neighbors to the English –but they were not pacifists. Inter tribal warfare was part of the early New England life, and the Wamesits, like most of the Algonquin Totem of the Wolf tribes, were warriors, battle scarred by wars with the Mohawks, and Northern Tarratines. (Abenakis) Passaconaway himself boasted of his battle exploits in his retirement speech claiming that no wigwam pole had “so many scalps as his.”147 He spoke of his former “delight” in war. 148 The plaque on his Edson Cemetery statue describes him as a “Great Warrior.” When Massachusetts Chief Chekatabutt organized his ill-fated 1669 New York expedition against the Mohawks, Historian Louise Breen reported that he “met with the greatest success in recruiting warriors at Wamesit.” 148A Gookin and Eliot advised against the expedition and took credit for limiting participation to five braves who wanted to avenge the Mohawk killing of Numphow’s brother, but Gookin also reported that “the Wamesits suffered more in the late war with the Mohawks than any other praying town-“150 . Another account claimed that they lost 50 chiefs. 149 ( Chekatabutt himself was among the fallen.) The contradiction has been explained by Cogley as the application of one account to Wamesits generally and the other to the Praying Village proper. Even just those five warriors would have been a good representation of the praying village’s small population of military aged men. One “principal man” from the village was killed. 151 They may not have seen action in that earlier battle, but Wamesit detachments from both Lowell and Marlborough 152 provided their quota for Gookin’s levy of 1/3 of all able bodied men raised from each praying village to fight alongside English forces in the July 1675 Mount Hope expedition. Gookin also wanted a combined English Indian force to occupy a fortified ring of Praying villages, Including Wannalancit’s fort, as a defensive bulwark. 153 Bodge thinks that some Wamesit braves defected to King Philips forces after the Richardson incidents. 154 Only Wannalancit’s restraint prevented his braves (probably including Wamesits) from attacking Mosely up at Pennacook. Adding possible historical context to a current debate, New England Indian warriors painted their faces red “especially (as Gookin wrote) when they are marching off to their wars and hereby, think, are more terrible to their enemies.”155

Christian Indians were part of a convergence of factors turning the tide against Philip. Despite heavy English losses, Sudbury proved a hollow victory. On May 19th, Indians suffered heavy losses in a surprise attack on their villages near Turners falls. Many of the Indians were asleep. 157 The Indians regrouped to kill a large number of the withdrawing English forces, but Indian tactical skills were no longer enough to overcome a worsening logistics situation. After Turners Falls, demoralized Indians were on the move, their operations often reduced to foraging for food to survive. They were cut off from their hunting and fishing sources and vital corn supplies. 158 There were only four more attacks on Settlements. Indian alliances were beginning to fracture, especially the vital Narragansett partnership after their chief Canochet was captured and executed. 159 Philip became increasing isolated as his allies sued for peace. After Turners Falls, King Phillip was one of only two Sachems left fighting on in Massachusetts. 159AThe war was becoming an exercise in hunting down small parties of “almost defenseless” enemies. 160 Many starving Indians just wandered home. The English issued a proclamation offering amnesty for Indian fighters reserving punishment for the “instigators and exceptional bloody”. 161 In practice it was sometimes more of an Unconditional Surrender policy– often applied with more severity than Grant’s. In some cases, they reneged on negotiated terms for “good quarter,”162 and the duped Indians were sent to the Boston Common Gallows.

On October 10th, 1675, the English had declared a day of Public Humiliation. By June 20th of 1676, the outlook had improved enough to declare a day of Public Thanksgiving. 163 On August 1st, the Council dismissed the garrisons of Chelmsford, Billerica and Concord. 164 On August 12th, King Philip was cornered at his Mt Hope lair and killed by another Indian, effectively ending the war, at least in Massachusetts, although it didn’t officially end until April 12th, 1687. The front moved North into Southern Maine where tribes joined with the French to hold back the English from advancing beyond the Kennebec River claimed by the French as their border. The never completely halted fighting continued on through several more, separately designated, but really one continuous war – fought mostly in Maine, but including deadly attacks on Deerfield, and, closer to home, Dunstable, Groton, Andover, Billerica and Haverhill.

Wannalancit and some of his followers returned after surviving a severe winter up near where the Connecticut River crosses into Canada. 165 Others, especially those fearing harsh English justice fled North and East to the Pennacooks hoping to blend in or seeking Wannalancit’s protection. 166 Some joined up with Kangamangus who had gone North to continue the fighting. Wannalancit resumed leadership of the southern New Hampshire Pennacooks, giving Wannalancit and his nephew a kind of dual recognition as Pennacook Sachems. Wannalancit was seen as head of the Pennacook peace party 167 and Kangamangus headed the “warlike Majority.” 168 Wannalancit emerged from his isolation to take a role in winding down the war and encouraging surrenders. 169 In June, he brought in seven English captives he had rescued to Major Richard Waldren. 170 Waldren operated a trading post and held political and military positions in Dover,NH. 171 His post was implicated in illegal alcohol sales and other sharp practices. 172 On July 3rd, summoned by Waldren, Wannalancit and the Saco Sachem Squando signed a treaty committing about 300 Indians under their jurisdiction to renunciation of further fighting and a promise to report hostile plans by other Indians. Numphow’s son, Sam Numphow, also signed. 173 In September, Wannalancit was enlisted as a peace broker again. He helped organize a gathering of about 400 Indians at Richard Waldren’s on September 6th, 1676. Some historians think the events of that day were a negotiated surrender, 174 but other accounts describe the use of a War Games type stratagem where the English persuaded the Indians to fire their guns first only to be facing loaded and primed English Weapons, including a cannon. The defenseless Indians were “handsomely surprised.”175 Approximately 200 were separated out and sent south- some to the Gallows and others to be sold into slavery. Among those executed were the two Chelmsford Arson villains Nathaniel and One Eyed John Monaco. Monaco paid the price despite evidence of Wannalancit’s intervention on his behalf. 176 Waldren sent a second group of Indians to Boston soon after where more of them were sold. Even some of the most “trusted praying Indians”, including Sam Numphow had difficulty talking their way out of Waldren’s net. 177

Many Indians, including Kangamangus saw the incident as a betrayal and may have blamed Wannalancit for his complicity. 178 More of them deserted him and headed North to join up with Kangamanus or headed further North toward Canada along with many other Indians displaced by the war or crowded out by advancing settlement The movement was becoming a migration. The St. Francis branch of the Western Abenaki, which had villages in New York and Odanak Quebec, became a major refugee settlement destination for these Indians. 179

The diminished Pawtucket and Wamesit tribes drifting back to Lowell found a very different place than the one they left. Land had been, plowed under and “sown and planted” –essentially taken over by the English. 180 The new fort stood on top of their fishing site. (Gookin believed that some of the accusations lodged against the local Indians had been “instigated to secure Indian land”) 181They had no corn supply – and were still vulnerable to Mohawks raids. 60 of the Wamesits ended up on Tyng Island. Some of their children were ordered to be put forth to English Service by the Chelmsford Selectmen. I82 Some others were bound out to service in a “different location.” 183 They never returned to the Falls. 184 In March of 1677, Wannalancit’s sons exchanged shots with the dreaded Mohawks across the river in Pawtucketville. 185 In September of the same year, the Wamesits joined the Migration. 186 They were escorted North by St. Francis Indians– their approach being sometimes described as an invitation and sometimes an abduction – the first interpretation supported by the presence of Wannalancit’s brother in law and other relatives of his wife among them. 187(St.Francis is another name for the Western Abenaki tribe) For these Wamesits reaching Canada, hard travelling on their “Trail of Tears” had ceased at last. Some Wamesits on Tyng Island may have followed later. (see footnote 202 infra sources.) There were likely some other Wamesits and Pawtuckets who remained in the Tewksbury Lowell area. It was one of the four areas designated for continued Indian occupation. 188 (Gookin wrote that 4 of 16 praying towns survived the war.) although its life as a praying village had come to an end. By no later than 1686 with most of their land taken over or sold, most of any remaining and, now effectively “homeless” Wamesits and Pawtuckets, were gone, 189 many resettling or merging among the Abenakis. 191 As Descibed by Lee Sultzman in New England Genealogy “—after 1676 they (The Abenakis) absorbed thousands of refugees from southern New England displaced by settlement and the King Philip’s War. As a result, descendents of almost every southern New England Algonquin tribe (Pennacook, Narragansett, Pocumtuc, Nipmuc) can still be found among the Abenaki, especially the Sokoki (western Abenaki).”(Pennacook as used here probably included the Wamestis, Pawtuckets and other Penacook tribal groups). 192 The Pawtuckets and Wamesits continue to be recognized in the “Our People” Section of the Greater Abenaki Nation Constitution 193, but Passaconaway’s once mighty federation which clung to existence under Wannalancit had finally “vanished away. “194

The exodus of the Wamesits and Pawtuckets ended the existence of tribal units in Greater Lowell, but many Indians remained. Even before the war, some Indians had begun to integrate into the local economy. Some hired out to Chelmsford residents. After the war, prisoners, orphans, and other displaced Indians found their way into the economy some as slaves or indentured servants and some as wage earners. There was a distribution process for children. Gookin served on a committee to find homes for these children and took two into his own home. 195 Moore wrote that post war Indians were a significant part of the household based economy. Indian “Tenant farmers, hired servants, and farmworkers” were reported by Charles Carroll in Cottom Was King. Ethnicity In Lowell authors, Robert Forrant, Phd. and Christoph Strobel, Phd, wrote that Native American women, including a contributor to the Lowell Mill Girl publication, The Offering, worked in local mills.196

Indian Culture survives in the Greater Lowell Area. Today, The Greater Lowell Indian Cultural Association keeps Indian traditions alive, protecting them and passing them on to future generations. The group has organized and participated in Pow Wows and other ceremonies and other events. They conduct class visits, public speaking events, and other community outreach efforts to honor and increase awareness of the indigenous peoples who lived here generations ago. Two group members are Pawtucket descendants. 197

The exodus was accompanied by liquidation of land holdings. Major Henchman made a number of purchases. 198 On August 19th, 1665, Bess, wife of Nob How (Numphow) sold substantial Dracut holdings to Captain Evered alias Webb. The consideration was a pound of tobacco and four yards of duffel cloth. Part of the purchase was resold to Samuel Varnum. 199 In August of 1668, Evered was pulled overboard by a whale and drowned. A shadowy character, there was speculation that Evered was the inspiration for Captain Ahab. 200 In 1681, Sarah Onomog got permission to sell her Marlborough land. 201Two years later, Colonel Tyng regained possession of Wikasauke (now Tyng) island in return for his services caring for the Indians, 202 and, two years after that, Bess Hob, her son John Numphow, and John Tahattan’s daughter Sarah closed out all their Billerica holdings in a sale to the town, partly confirming prior sales, for 50 Shillings each, 203 The major real estate transaction closed in1686. Tyng and Thomas, now Major, Henchman fronted a fifty-person syndicate which purchased all Lands West of the Concord River and across the Merrimack West of Beaver Brook. The transaction known as the “Wamesit Purchase” was the effective end of Indian Land ownership in Greater Lowell. 204 The 212 Acre “Old Planting Ground” was sold by Wannalancit to Tyng separately. 205 The preceding is a partial summary. There were other prior and subsequent conveyances along with legislative actions and title disputes which continued into the early eighteenth century, but the list substantially summarizes the divestment of Indian land holding in the Greater Lowell area

The Indians never seemed to get value in their sales. There were often other considerations such as protection from Indian enemies, but the Wheelwright deed and Bess Hob’s later Dracut sales have an echo of Peter Minuit’s purchase of Manhattan. Deeds, including the Wamesit purchase, often retained hunting and fishing rights but they were of limited value to the Indians as most of them were gone and the rest were soon to follow. As described in Ethnicity, the situation was compounded by a bad balance of trade cycle where their increasing dependence on English trade goods force them to sell off land when overtrapping of fur animals left them nothing left to exchange but pieces of their land. 206 (trade goods consisted of utensils, tools clothing and guns. Gun control was an issue then too. The English made sporadic efforts to enforce bans, but, as in the case of alcohol, there were always sources. The French and Dutch supplied weapons. The Indians often raised a Mohawk defense rational for keeping guns, an exception supported by Eliot. 207 Like Passaconaway, King Philip was forced to give up his guns, 208 but still managed to restock in time for his coming war)

Ethnicity described the Indians’ plight as “being ethnically cleansed out of the lower Merrimack valley by English colonists.” 209 The process contained some of the ethnic, religious, and cultural prejudice associated with the “ethnic cleansing” term but, perhaps just as significantly, The Indians were in the path of a demographic tsunami which saw the English population approximately double between 1660 and 1680. 210 The Indians, useful to the Settlers at first, became mainly just in the way, The English tolerating “them until they could conveniently drive them away,” 211 Their sense of entitlement was reinforced by the Puritan belief, that they were a special people, as described in a PBS program, The Puritans “chosen by God to fulfill a special role in human history: to establish a new, pure Christian commonwealth” 212 and by Bodge “confident that god hand opened up America for the exclusive occupancy of Puritans and Pilgrims.” 213

The fates were not equally kind to those who played a role in the story of the Greater Lowell Indians. During the war, The Wamesits and Pawtuckets were at different times assigned guardians to look after their interests. 214 Thomas Henchman had a garrison house in Middlesex village. He was a Major and commanded the “Upper Middlesex Regiment” and participated in several expeditions. At war’s end he commanded the new fort near the falls. 215 In addition to his guardianship role, he had a history of commercial and real estate dealings with the Indians. He made numerous land purchases from the Indians. He shared the trade monopoly and later became part of Tyngs’s Wamesit Purchase syndicate. At war’s end he commanded the fort at the Falls. Another guardian, Henchman’s son in law, James Richardson, faced into the teeth of deadly combat several times. He survived the Brookfield ambush and was rushed to the relief of the Sudbury siege. He continued to serve after the war ended in Massachusetts, and was killed in another ambush at Black Point Maine in August of 1677. 216

The other guardian, Col Johnathan Tyng living in what was then Dunstable, was commended for staying put in his Dunstable home after many of his neighbors fled 217 – but then he had a lot to protect. Tyng owned what was probably as close to an Ante Bellum Southern plantation as could be found in New England His mansion was one of the “largest privates structure between Woburn and Canada”, 218 built about the same time as the Bowers house. According to Waters, he owned slaves to work his extensive holdings. 219 In 1697, a year after Wannalancit’s death, Tyng was before the General Court presenting his bill for services during his ward’s last years. 220

Kangamangus, often described as the “Warlike Kangamangus,”221 fought on up north. By 1685 he was recognized as a dual Sachem of the Pennacooks. He kept up some continuing contact with Wannalancit who may have brought him to the table for 1685 peace talks. 222 Cowley wrote that the “Indians never forgot a friend or forgave a foe,”223 and Kangamangus had a long memory. In 1689 he got his gruesome revenge for Major Waldron’s treachery in the 1676 Dover sham fight. Kangagamangus and his raiders, with some inside help from Indian employees of the post, 224 broke into Waldren’s compound killing 23. Waldren himself did not die until suffering lengthy torture where some of the Indians slashed “Accounts Crossed Out” onto his chest. 225 Kangamangus probably died before his uncle. Could a feeling of grim satisfaction, even if fleeting, have passed through Wannalancit when he learned how Waldren met his Karma at the hands of his nephew? Who knows? We do know that this gentle Chief with the meek name (Wannalancit translates as “Pleasant breathing”227) followed his father’s mandates. One of them was “Love the English, Love their God” Despite English ingratitude and mistreatment, Wannalancit managed to do both. 227A

Gookin continued as a colony leader after the war concluded. In 1676, he had lost his position in the Council of Assistants. His defeat was attributed to popular anger at his support of friendly Indians. He regained his office in the next term and was also appointed Major General. Gookin’s life paralleled a time when English politics still cast a long shadow over colony affairs. He was a forceful advocate for the colony in its Charter dispute with the crown. His efforts were personally costly. He lost his military positions after the Charter was revoked in 1686 and suffered other setbacks. Despite making his mark with business interests and public positions – in three colonies, his life ended in poverty. 228 His friend and colleague John Eliot took up a collection for his widow.229

Eliot continued his ministry with his diminished parishes until his death in 1690. Despite his devotion to his mission and continued preaching, little of his effort survived. The original Natick village was the last survivor. By 1716 its church had dissolved. By 1725, the land was sold off. 230 Natick translates as “My Land” 231 but as befell most Indian Land holdings, “My land” became “their land.”

“Vanished away “but the Pawtucket and Wamesit names are all around us. Both have sections of municipalities which carry their names. The Pawtucket name appears on streets, a diner and a school and other enterprises. In Tewksbury, The Wamesits have their Park in West Tewksbury with the Kaufman statue. Wamesit is the name of Tewksbury’s Masonic lodge and recently opened Bowling complex. Wamesit nearly became the name of an entire town. Samuel Hunt, sometimes known as the “father of Tewkbury” played a role in Tewksbury’s 1734 separation form Billerica. An earlier, unsuccessful, effort by Hunt would have created the town of “Wamesit” out of the territory comprising the Wamesit Purchase. 232 The School Street Area in Lowell was once known as “Wamesit Hill”. Nursing homes and a community near Concord carry the name of the parent Pennacook tribe. The Wannalancit name survives on a mill, street, and a Boy Scout District. His nephew has the Kangamangus Highway, hiking trails and a lodge. His father has a beach, campsites, and a golf course in his Litchfield NH final home. Dracut Historian Roger Coburn wanted Dracut’s Long Pond renamed Lake Passaconaway in memory of the Bashaba’s presence there. 233 Lucy Larcom, Lowell Mill Girl and Poet, contributed to keeping their memories alive by naming New Hampshire Mounts Passaconaway in Lebanon and and Wonolancet in Waterville Valley. 234

Three years ago, high winds and the centuries and claimed a well known living monument to Greater Lowell Indian heritage, the “Pow Wow” Oak, which stood on Lowell’s (formerly Tewksbury’s) Clark Road, until it came down in 2013. The Molly Varnum Chapter of the D.A.R. historic marker says the Wamesits met “under this oak” for their “Pow Wows, their Peace Conferences, and their Councils of War.” The ages attributed to the tree are hard to reconcile with the account of these tribal activities which would have occurred earlier. However, the site is in former Wamesit territory, possibly near their old capital, and could have seen these activities at some earlier time –or might have even seen gatherings of some Wamesits who remained in the area after the main body of the tribe was gone. Even with these questions, the site has probably acquired its own reality as a symbolic reminder of the Native Americans whose spirits remain a presence – a reminder of the moccasined feet which preceded our SUVs down these roadways – perhaps truth can happen to legends a well as William James’ ideas.

After the Exodus, Wannalancit seemed to live like a ghost, wandering the woods at the head of a small group. In 1683, the General Court awarded him10 Pounds as compensation for various treaty violations. 235 There were reports of Wannalanlcit “tarrying” at Pennacook and other places along the Merrimack. 236 In 1685 he appeared in Dover at the head of 24 men assuring local authorities of his peaceful intentions. 237 In 1692, his peacemaking services were sought again in connection with the then raging King Williams War. 238 He came in under a flag of truce in 1692, was taken into custody and then released to Colonel Tyng as guardian. He remained with Tyng until his death 1n 1696, and is believed to be buried on grounds formerly of the Tyng Estate. Cowley said that Wannalancit headed north after the outbreak of War because of his determination to “act the part of a neutral.” 239 Wannalancit was neutral in following his father’s command and wanting to keep his people from being pulled into the vortex of the War – but it was in some ways like American neutrality when World War I broke out –looking to avoid being dragged in while his heart was with the English. It was rewarded with ingratitude on one side and accusations of selling out by the other.

Robert Boodey Caverly, writing in 1882, suggested building a dual monument statue of Eliot and Wannalancit at Fort Hill Park, recognizing their dual contribution in protecting the Lowell area form some of the worst ravages of the war (13 towns destroyed and 52 damaged.) 240 Eliot’s evangelizing and establishment of the fourteen praying towns removed many Indians from Philips recruiting pool- many of them taking the field against him. His life and work could well merit another memorial in Lowell, although the Summer Street Church which carries on his memory in its name, its good works, and in bringing the gospel to people of different cultures stands as an eloquent memorial to him in its own right.

Wannalancit’s “neutrality” reduced Chelmsford’s exposure to causalities and destruction-a role indicated in an interview with Chelmsford’s minister John Fiske. Reflecting on Chelmsford’s minimal damage during the War, Fiske commented “Thank God” to which Wannalancit replied “me next” indicating his second only to God role. 241 His role may have also have prevented war time loss of life among his people, although it didn’t prevent them from being swept away in the Diaspora which followed. Wannalancit is remembered by a stone monument on the grounds of the Innovation Charter School in Tyngsboro, once part of the Tyng estate. A Plaque is attached to a rock where, according to the Nashua Telegraph, article by Joseph G. Cote, citing Herb Morton, a member of the Tyngsborough Historical Commission, Wannalancit is said to have spent his last days looking out at the river and across to Wickasauke (Wicasee) and would, quoting Morton, “—pine away for his lost life.” 242 Looking out at the river, the old Chiefs’ mind must have drifted back to better days. Some of those better days were in Lowell where he walked to church and built his fort. It would be a good place for a memorial to him, perhaps reunited with his friend Eliot, and would remind us of this Lowell History chapter which opened with hope and ended with heartbreak for these people who once lived among us.

Entrance to Fort Hill Park, Lowell, Mass.

“Fate swept us away, sent my whole brave high born clan to their doom. Now I must follow them.” Seamus Heaney Beowulf

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks to the scholarship of the authors of the authors living and dead listed below. Thanks also to my wife Mary for her advice and assistance, my Assistant Kathleen Martin in getting this article ready for publication and keeping the office on an even keel during the process, my sister Libby Gaffney’s genealogy research keeping me from following an appealing but false lead into a embarrassing dead end, My granddaughter Chloe Morrissey’s Photography, and helpful Input from Greater Lowell Indian Cultural Association members. All of these and others share in any credit due this work. The blame, where applicable is all mine.

DISCLAIMER

The Acknowledgements, Sources Section, and footnotes in this article do not imply any indorsement of either the viewpoint or the accuracy of any part of this article by the sources cited. There were some instances where I cited a work which opened up a new area of inquiry to me but the interpretation and presentation in this work was sometimes for better or worse (more likely the latter) my own.

Please see comments for bibliography and footnotes.

SOURCES

Allen, Wilkes The History of Chelmsford fom its Origins in 1653 to the year 1821

Haverhill, 1820 (“Allen)P.N. Green 1829

Bailey, Sarah Loring Historical Sketches of Andover (“Bailey”) 1880 Boston Houghton Mifflin

Beals, Charles Edward Jr. Passaconaway in The white Mountains (“Beals”) Boston, R. Badger, 1916

http://www.BigOrrin.com (“ The Identity of the Saint Francis Indians

from Gordon Day’s 1981 study on Odanak (“DayBigOrrin”)

Breen,, Louise Transgressing the Bounds Subversive Enterprises among the Puritan Elites in Massachusetts (“Breen”) Oxford University Press 2001

Brodeur, Paul King Philips War in Marlborough(“Brodeur”) slide show presented to Marlborough Historical Society July,1st, 2012 and email 4/20/2105 (“email”)

Caverly, Robert Boodey, History of the Indian Wars of New England with Eliot the Apostle. (“Caverly) WF Brown & Company, Boston 1882

Census Bureau, Dept Commerce 1998 World Alamanac Book of Facts P.378 (Census)

Coburn, Roger Silas History of Dracut MA (“Coburn”)citizen 1922

Cogley, Richard W. John Eliot’s Mission to the Indians before King Philip’s War, (Cogley)Harvard University Press 1999

Greater Abenaki Nation of the Wabanaki Confederation of N’dakinna (“Constitution”)

Cotton Was King, A History of Lowell, Ma Edited by Arthur L. Eno Jr. J Frederick Burtt, Passaconaway’s Kingdom. (“Eno/Burtt) Charles E. Carroll, The First White Settlement (“Eno /Carroll”)NH Publishing Co in Collaboration with Lowell Historical Society 1976

Cowley, Charles; Memories of the Indians and Pioneers of the Region of Lowell. Lowell, Stone and Huse, 21 Central St. 1862

Drake, Samuel G. Old English Chronicle,”Drake”) Boston Samuel A. Drake, 1867

Ellis, Geo W/ Morris John E King Philips War (“Ellis”) The Grafton Press 1906

Forrant, Robert Phd, Christoph Strobel Phd. Ethnicity in Lowell(“Ethnicity”) Lowell National Historical Park, contacting with UMass Lowell History Department, 2011

Gookin Daniel, Historical Collection of the Indians in America December 7th ,1674

Apollo Pres Boston (Gookin I)

Gookin Daniel Historical Account of the Doings and Sufferings of the Christian Indians in New England 1675-1677 (Gookin II) American antiquarian Society,

University Press 1836,

Greater Lowell Indian Cultural Association. http://www.glica.net/ (“Glica”)

Hadley, Amos History of Concord, New Hampshire, by Concord (N.H.). City History Commission; Lyford, James Otis, 1853-; Hadley, Amos; Howe, Will B,1903 (Hadley)

Hazen, Henry A., J A Billerica History (“Hazen”)Williams and Company, 1887

Illustrated History of Lowell and Vicinity (Courier), Courier Citizen Company, Lowell Ma. 1897

Morton, Thomas New English Canaan (“Morton”) 1637

Ma Archives Ancient Plans V112,(“Archives”)

Malone, Patrick M.The Skulking Way of War(“Malone”) John Hopkins University press 1991

Moore, Joseph Price III Native Americans in Colonial New England and the Modern World System. (“Moore”) Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School- New Bunswick Rutgers, Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program History.

Nashua Telegraph, May 15th, 2011, Native Friend to Colonists Recalled “Telegraph”) Joseph G Cote citing Herb Morton, of the Tyngsborough Historical Commission.

Natick Historical society Web Site (“Natick”) John Eliot and Praying Indians Section

PBS God in America, People and Ideas: the Puritans. (“PBS’)

Pendergast, John A Bend in the River, (“Pendergast”) Merrimac River Press, 1992 Pride Edward W. Pride Tewksbury a short History (“Pride”) issued by Tewksbury Village Improvement Association, Cambridge, Riverside press 1888Schultz,

Sultzman, Lee, New England Genealogy Abenaki History http://www.tolatsga.org/aben.html(“Geneology”)

Tewksbury Town Crier, Jon Bishop 6/30/2012 Pow Wow Oak Dispute Over (“Oak”)

Eric B, Tougas Michael J Schultz. King Philips War (“KP’s War”,) The Country Man Press, Woodstock Vt. 1957

http://www.smplanet.com/teaching/colonialamerica/wars/kingphilip (“Planet”)

Trent and Wells, Colonial Prose and Poetry Vol II Beginnings of Americanism 1650 -1710, Daniel Gookin (“Trent and Wells”),

Rev. Wilson Waters, History of Chelmsford MA (“Waters”) Courier Citizen Company Lowell MA 1917. Chapter One written by Henry Perham

Weeks, Alvin G. Massasoit(“Weeks”) privately printed 1921 (“Weeks”)

Wikipedia Penacook Schaghticoke (town), New York.

FOOTNOTES

1. http://www.redmen.org

2. Beals P 13

3. Beals P.19

4. Gookin I P.14.) See Hadley P.68

citing Morton, Moore P.120

4A Gookin I P.13

5. Beals, P 26

6. Beals P.22

7. Beals P.13

8. Beals P. 13

9. Gookin I P. 14

10. Beals P. 20

11. Cowley P.3

12. Drake 239

13. Coburn P62, Courier P.65

14. Bodge P.161

15. Brodeur Email

16. Morton cited in Coburn P.32

17. Allen P. 141, Mason. P.16, Green P. 69

17 A Courier P.64

18. Delete

19. Delete

20. Beals P.20

21. Malone P.35

22. Ethnicity P.13 Beals P.17 Eno/Burtt P.4

23. Gookin I P22

24. Beals P 32

25. Gookin I P 22

26. Coburn P. 31

27. Beals P. 32

27 A Weeks P.247

28. Cowley P. 10

29. Waters P .77

30. Beal Ps. 31,33

31. Cowley P. 7

32. Cogley P. 71

33. Waters (Perham Chapter) Ps 2-34detailed summary of Chelmsford grant and subsequent boundary adjustment

34. Allen P 144, Gookin I P46

35. Waters (Perham Chapter) Ps 29-34

36. Courier P.66

37. Deleted

37A Moore Ps. 232 239 Coburn P.37

38. Pendergast P 53, Coburn P. 39

39. Hadly P.73

39 A Cowley P.10

40. Cowley P.4

41. Cowley P.11

42. CowleyP.8, Cogley 229

43. Pendergast P.31

44. Gookin cited in Cowley P.13

44A Allen P. 141

45. Gookin I P74

46. Cowley P.13, Waters P78

47. Water P. 78

48. Water P. 80

49. Pendergast P.52, Coburn P.36

50. Waters P79

51. Coburn P.34

52. Cowley P.7

53. Coburn P.33, Beals P.36 Waters P.82The

54. Hadley P.69

55. Potter Ch5, P. 5

56. Coburn P.36 Beals Ps.36/37

57. Deleted

58. Pendergast P.59

59. Pendergast P.41

60. Water P 82

61. Cowley P.12, Courier P. 66

62. Waters P.63

63. Cowley P.12, Water P.78

64. Allen P.142, Courier P.91

65. Courier P.91

65A. Courier P. 91

66. Allen P.16

67. Courier P.81

68. Beals P. 24, Caverly P.125

69. Beals Ps. 24/25

70. Hadley P.70

70 A Hadley P.69

71. Drake P. 2

72. Drake P.59

73. Bodge P.250 beals p.62

74. Pendergast P.41

75. Gookin II P.463

76. Coburn P. 46

77. Bodge P. 76, Potter Ch V Ps 12,13

78. Hazen P.107

79. Hadley P.106

80. Coburn P. 46, Potter Ch V P.13

81. Coburn P.46

82. Hazen P. 107

83. Bodge P. xl

84. Coburn P. 46, Hadley P.76

85. Waters P.96 Bodge P. 25

86. Courier P.121

87. Bodge P.ix

88. Waters P82 Gookin I P.38

89. Waters P.59

90. Gookin I p11

91. Cogley P.239

92. Gookin I p11

93. Weeks P. 239, Drake P.106

94. Courier 115

95. deleted

96. Waters 98

97. Brodeur Pt 1 P.68, Drake P.137

98. Waters P. 105

99. Cowley P.16

100. Waters P.115

101. Cowley P.16

102. Gookin II P.474 Cowley P17

103. Gookin II P.475

104. Potter Ch V P.13

105. Gookin II P.470

106. Cowley P.17

107. Bodeur Pt 1 P.38

107A Bodge P. 161

108. Waters P. 107

109. Drake P. 150 Waters P. 98

110. Bodeur Pt 1 P.65

111. Waters P. 96

112. Brodeur Pt 3 P.1

113. Gookin II P.482 Beals P.66

114. Gookin II P. 483, Beals P.67, Waters P.101

115. 116 Waters 87

116. Gookin II P. 471

117. Cowley P.18 Waters P. 100

118. Gookin II P. 485

119. Waters P.101

120. Gookin II P.485

121. Cowley P.19, Hazen P.114

122. Cowley P. 19

123. Waters P.110

124. Waters P.1O9

125. Waters P.100

126. Bodge P222, Gookin II P.438,439

127. Gookin II P. 439

128. Caverly P. 105

129. Drake P. 159

130. Waters P.114

131. Courier P.67

132. Gookin II P.463

133. Beals P.67 Gookin II P. 491

134. Cowley P.16

135. Beals P.67 Caverly (Eliot the Apostle) P.75

Coburn P.46

136. Bodge Ps. xvii, 173, 100

137. Pendergast P.79

138. Cowley P.18

139. Caverly P.210 Hazen P. 114

140. Waters P.111

141. Waters P.119

142. Waters P. 116

143. Bodge P.xx, Ellis P. 209-213

144. KP’s War P.213-220

145. Drake citing More P.285

145A Malone P. 114

146. Caverly, Eliot the Apostle P.32 Committee of Interested Citizens, Plaque,Wamesit Park, Telegraph

147. Beals. P.15 Potter Chap V P. 6

148. Courier P. 66

148A Breen 169

149. Cowley P. 13.

150. Gookin II P.48

151. Cogley Ps. 151,152

152. Brodeur Pt 1 P.50 Gookin II P. 442

153. Gookin II P.436, Hazen P.117

154. Bodge P. 251

155. Gookin I P.13 Beals P.22

156. Delete

157. Drake P.239

158. Bodge P. vii

159. Caverly P. 203

159 A Coburn P. 64

160. Bodge Ps xxi, xxii

161. Bodge P.255

162. Bodge p. 360

163. Drake P 267

164. Water P.120 end P14

165. Beals P.69

166. Bodge P.xxxii, Waters P. 126

167. Hadley P.79

168. Hadley P.78

169. Drake P.275

170. Cowley P. 20

171. Waters P.120

172. Bodge P.223

173. Potter CH V P.16 Bodge P.254

174. Bodge P.256

175. Caverly P. 247 Beals P.71

176. Caverly P.127

177. Bodge P. 259

178. Ellis P.286, Beals 72

179. Day/Big Orrin

180. Hadley P. 77 Ethnicity P23

181. Waters P.96

182. Gookin II P.533

183. Cowley P. 20

184. Coburn P. 51