Home for the Holidays: Cowboy Christmas

Home for the Holidays:

Cowboy Christmas

By Henri Marchand

“The memories of childhood have no order, and no end,” wrote Dylan Thomas in Reminiscences of Childhood. A popular holiday song claims that, “there’s no place like home for the holidays.” These lines come to mind as my family prepares to celebrate Christmas, 2020.

We cannot see nor can we celebrate Christmases yet to come but even as we create new Yuletide traditions and experiences, we easily recall and readily share stories with family members and invite the comforting spirits of Christmases past to adorn another Christmas season. In so doing we gift pieces of family history to our children and grandchildren and family members yet to come.

House exterior – 2018

Since 1975, my wife and I have celebrated Christmas in several homes, for the first five years by ourselves, later with our children and grandchildren. We spent the latter part of each Christmas day at what we considered the extended family home where I grew up. We returned regularly to celebrate not only Christmas but other holidays, birthday, graduation and special theme parties, and weddings.

Three generations of my family lived under one roof, creating moments and memories tied to the space and structure, giving our home something like a soul if that can be said for a house. Over the years, the house, a large, roomy Colonial Victorian, sheltered our nuclear family that included Memère Brouillard and Aunt Rose. Tech students rented two rooms from September to May and relatives visiting from Quebec, usually when an elderly aunt or uncle passed away, stayed with us.

Prior to my parents purchasing the house at 118 Riverside Street in 1953, five other families called it home. The house was built in 1896 by George C. Osgood, a doctor and apothecary who bought the lot in 1891 from the estate of Ezra B. Welch. Welch acquired the land and earlier buildings from a family named Pierce when the area was still farmland. The gnarly remnants of an apple orchard held out in our neighbors’ back yards in the 1960s. Osgood and his wife Louisa had three children—John, Harry and Mary. They called the house home until June of 1903 when they sold it to Louis Olney, a Textile School professor of dyeing technology. Olney and his wife Bertha also had three children—Edna, Margaret and Richard. They reportedly kept a pet monkey and a goat.

I picture the Osgoods and the Olneys celebrating the holidays in their own times, in more formal attire and the home’s more formal furnishings, navigating heavy snowfalls and the still thinly developed area in sleds and sleighs. Recently posted photos on Facebook capture Riverside Street across from the Osgood’s home on February 1, 1898. The view is towards Moody Street (now University Avenue), the sky is cloudy, the ground covered in deep snow and there are only three homes all along that side. Young trees, presumably elms line the street and the street light is a gas lit Victorian. A woman poses on the front porch of the gambrel house overlooking the Merrimack River. A child, half obscured by snow, plays in the yard. Some fifty to sixty years later that would be my siblings and our neighborhood friends.

There were three other, short-term owners after Louis and Bertha Olney died in an automobile accident in 1949 and before my parents moved in when I was two weeks old. It was a large home and over the years my parents filled it with eight children—Monique, Gerard, Henri, Andre, Louise, Rene, Paul and Anne Marie. It became the place where our extended family gathered for informal visits and for holiday celebrations. And where childhood memories were created and where they reside still.

An early memory is of watching Mom and Memère prepare special meals, bake pies and cakes, and fry doughnuts. An incentive to behave as we observed was the promise of raw pie dough and cake batter treats. We each took turns visiting Memère and Aunt Rose who lived upstairs in an in-law suite created by a previous owner in 1952. They were my parents’ live-in child support and we happily joined them for lunches and seemingly endless games of cards, checkers and Parcheesi.

Halloween was a memorable season as the home lent itself to our imaginations and to the telling of ghost stories with its long hallways, nook stairwells, connecting rooms and passageways and the not-so-secret, secret room in the library Olney added in 1922. My Dad had a flair for embellishing stories whether fact or fiction. He claimed that the Olney’s pet monkey was buried somewhere in the yard or beneath the basement floor; that ghosts wandered the halls and resided in the secret room; that a squirrel who camped out under the hood of his car dashed out clean-shaven one morning after he turned the ignition. He spun tall tales of treasure hidden within the walls and in as-yet-undiscovered secret spaces. The storytelling tendency was inherited by at least one family member. My sister Monique, not one given to lying, to this day swears that she saw Dad chatting and shaking hands with Santa Claus one Christmas Eve. She recalls her memory in fine detail, insisting that she heard the sound of bells as Santa flew up the chimney.

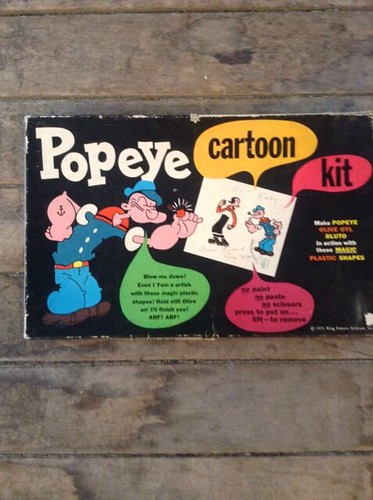

It is Christmastime that evokes the most vivid of home connected memories, with tinseled, Charlie Brown trees strung with colored lights, yuletide aromas of baking pastries, roasting turkeys and C7 bulb warmed balsam scents. There were white Christmases and bare lawn Christmases, rainy Christmases and warm ones, but in my selective, disordered memory they all appear white. There remains, stored in boxes, unsorted collections of black and white snapshots of our earliest holidays and color prints of later ones, some dated, some not, so that attaching an exact year to each memory is difficult and perhaps wholly beside the point. Nor is the memory of a particular holiday tied to the gifts received—Popeye Colorforms one year, a Boxer dog model another, and a visible man model later when I had expressed interest in becoming a doctor. But try as I might I could not figure out what organ went where and the patient was never made whole. Whatever the gifts, it is the memories that endure and give added richness and meaning to our family’s ongoing celebrations and the requisite disputations of dates and names and whose memories testify to the official record.

Colorforms

One Christmas in particular stands out, Cowboy Christmas, as my older brother Gerry and I came to call it. We were six and seven years old, our younger brother Andy five. The parlor that year was in what we later determined to have been Olney’s waiting room outside his library. The tree was another beautifully scrawny and heavily tinseled, glass adorned specimen. Gerry, Andy and I received cowboy hats, holsters with guns, faux leather gloves, a banjo and a ukulele. In memory, we also received matching homemade flannel shirts that year to complete the singing cowpoke look but the memory is disordered, like the photos stored in shoe boxes. In recently unearthed black and white glossies, we pose proudly, ready to gallop off on our imaginary steeds not in flannel but in long-sleeved jerseys. No matter, it was the high noon of TV westerns and we spent that Christmas vacation chasing each other and yippee ki-yaying around the house. I imagine now that my parents may have regretted their gift choices. It remains one of my fondest childhood Christmas memories, and even now, with an aversion to guns as gifts, I happily recall and replay Cowboy Christmas.

Cowboy Christmas – 1957

It wasn’t until several years ago that I learned that my cherished Christmas memory was created at a difficult time for my parents. I was visiting my Mom, reminiscing as we often did in her later years. As we spoke of the holidays I expressed how I remembered that Christmas as a wonderful time. She seemed pleasantly surprised and shared that for her and Dad it was a season of struggle. Dad, a self-employed painter and paperhanger, had been hospitalized and out of work. But they were determined to provide gifts for each of their children which by then included four sons and two daughters. They were equally determined not to let their worries diminish our joy. So they purchased inexpensive felt hats, six-shooters, and plastic cowboy instruments for my brothers and me along with other simple toys for our siblings.

As we got older Christmas memories shifted from toys to traditions. At some point, around ages eleven or twelve, we began attending Midnight Mass and enjoying a Réveillon, traditions carried down through New England from mostly farming communities to factory towns by our Quebecois forebears. The Réveillon followed Mass with an early morning buffet of Franco favorites—tourtière, salmon pie, apple and squash pies, homemade caramels, and fudge. Once done, it was off to the parlor for the sharing of gifts.

Over the years Christmas celebrations evolved as we each left the family house. We continued to return with another generation after time spent with our in-laws and at one point fifty-plus showed up at what was now a more reasonable time (4 p.m. rather than 1 a.m.) to feast, exchange gifts, and delight in an ever growing, ever lively Yankee Swap.

In the late 1990s my parents began a new, adults only tradition as a way to spend, relatively quiet, time with us. Two weeks before Christmas my brothers and sisters and significant others gathered for dinner with Mom and Dad, joined by our cousin Rick, who was by then living in Atlanta. Each of us was responsible for one course of a dinner that often broke with Franco-American cuisine traditions. Between the main meal and dessert we formed a production line to cut and wrap several batches of homemade caramel (with regular testing for quality control) and decorate the family tree. Mom and Dad delighted in these annual gatherings. Dubbed the Christmas Progressive Dinner, it was initially conceived as a traveling feast with a different course served at each of our homes but a blizzard the first year convinced us to abandon the travel part.

We have known for a few years that our long run of celebrations in the family home was nearing its end. As the years passed and we all had our own homes, the family house remained the common ground, our parents the center that held and their being and nurturing drew us all back at Christmas. My Dad died in 2001, my Mom in the spring of 2019. We agreed that we would not sell the home before one more Christmas season, one more round of gatherings to celebrate the memories and to say goodbye to the spirit of the place.

Living Room – 2018

Living Room – 2020

Our family house passed on to another owner this past spring and after sixty-seven years will no longer host our family’s holiday communal gathering. But it remains with us in muddled memories that “have no end” and in stories of Christmases past and of the people who have called it home. There is no longer a home spacious enough to accommodate fifty of us for a single holiday celebration so we will atomize and gather in cautiously smaller groups.

Covid Christmas 2020 will be celebrated with new traditions and family members, likely via new technologies. Photo moments will be saved with screen shots. Still, we will remember those that came before and will look forward to passing on, as one passes on family heirloom ornaments, those endless memories of Christmases past. Even as we look back, we will look forward to 2021 and to “Cowboy Christmases” yet to draw near.

Grandkids

A poignant holiday tale, very nicely told. I hope this receives wide readership. Happy holidays in this difficult time.

Great stories! I’ve got a lot of great memories from my college years living in that area. Thanks for sharing!

Beautiful family memories Henri. Thank you for sharing!

This brought so many memories. Miss those days so much. Thank you.

From the intimate to the universal, in concentric circles centered on beloved parents in an extraordinary home, to the nuclear and extended family then on to the Riverside Street neighborhood and to Lowell itself, Henri Marchand’s moving text will remain a classic for years to come. Thank you for inviting us to your family’s Christmas celebrations Henri. Merci for sharing your history!

A poignant, loving holiday memory! Thanks for sharing it, Henri.

Loved reading about your family and especially your Cowboy Christmas. Reading through your memories brought back memories of my own.Thank you for sharing your family story.

Thank you all for the kind reviews. Glad you enjoyed the read and the personal memories it stirred. Merry Christmas!