Capturing Lowell in a Single Line: “Cummiskey Alley”

A review by Richard Howe of

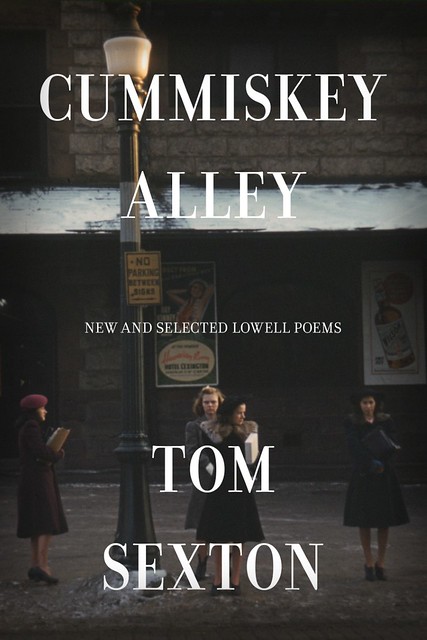

Cummiskey Alley: New and Selected Lowell Poems by Tom Sexton

At the end of the bottom shelf of my big bookcase, after all the histories, memoirs, and biographies that are my usual literary diet, sit two books about poetry: Can Poetry Matter? by Dana Gioia and How to Read a Poem by Edward Hirsch. I have these books because I know that poetry is a powerful part of our culture but poetry is also something I find elusive. When I scan through the magazines that still come in the mail and come upon a featured poem, I read it, but I don’t “get” it.

All that changes when I read a poem by Tom Sexton, a Lowell native, Lowell High Distinguished Alumni, and the former Poet Laureate of Alaska. Tom’s new book, Cummiskey Alley: New and Selected Lowell Poems, recently arrived from Loom Press. I read it immediately.

There is a saying that’s entered common usage to describe Lowell in the 20th century: “The Great Depression came early and stayed late.” Tom Sexton’s Lowell poems capture that sentiment with words and images and the feelings they evoke in the reader. Here is an example, set in the year of my birth:

Work

It was always scarce, a few piece-work jobs

in a shoe shop or at least that was that was the rumor.

1958 was anything but a very good year.

Fresh out of school, we lingered on the corner

of Merrimack and Central looking for work,

but it never came by. That was our joke.

We knew we were headed for the military.

If we were lucky, Big Al, who was a body man

and never out of work even though he never

finished the eighth grade, some said seventh,

appeared in his chopped and channeled Ford

and offered to drive one or maybe two of us

around the block with the windows down,

moving at a snail’s pace so we could be seen.

Near the back of the book in an autobiographical essay, Tom explains that the hopelessness he felt in Lowell led him to enlist in the Army and the Army, in turn, deposited him at Fort Richardson, Alaska. That was Tom’s introduction to the 49th state, a place he would return to as a civilian to make his home after finding the employment picture in post-military Lowell little changed from before. And it was in the Army that Tom, an indifferent student in high school, was introduced to books and the power of words.

He identifies as his first real poem one that traces his personal arc from joblessness in Lowell to opportunity in Alaska:

Pool Shark

He was an ancient gambler long absent

from the window table where the game

became a way of life, a badge of honor

where only the best were invited to play.

Dim-eyed and reptilian, Willie Provencher

sat on his favorite bench near the door

scanning the room for fish, and we came

duck-tailed and dumb from school to lose

at eight-ball to that dank and wrinkled shark

who held a dime store magnifying glass

to his best eye to line his shot before he slowly

chalked his cue then smiling ran the table.

He took our palm-wet quarters one by one.

A fingerling anxious for the sea, I left that world.

There’s no small change in this Alaskan city

where I live. Crude oil sets my table now

and sharks wear silk not threadbare overcoats,

a place where few ill bend to pick a quarter up.

I can see the earth’s inviting bend toward Asia

and from time to time when moonlight falls

through clouds as thin as window glass,

I long to shine like bait in Willie’s hand.

When I was young and snow fell, we cleared the driveway not with lightweight, wide-edged snow shovels of plastic and aluminum like we use today. No, we used ancient shovels of heavy wood and steel designed to cast lumps of coal into a basement furnace. Those shovels and my dad’s stories of a teenager’s recurring chore of shoveling coal from the driveway into the basement and from the basement floor into the household furnace formed my personal link to everyday life in that earlier era. Another of Tom’s poems better focused my image of that time:

Coal

It’s the early 1930’s and Mr. Farley driving

his black Packard 12, the finest car that will

ever be made, over Pleasant Street’s cobbles.

They’re on a cloud the way the Packard rides.

Mr. Farley has become a rich man selling coal,

the finest anthracite shipped from Pennsylvania.

He waves to the men walking to the tannery.

It’s wise to smile and wave at your customers.

He feels good that he recognized the small man

who bought coal oil to cure his infant daughter.

The lunch pails they carry are as black as coal.

I could have been an artist Mr. Farley muses.

A man who looks like a human raccoon waves

from one of Mr. Farley’s trucks. He smiles.

“The world will always need coal, Mrs. Farley,”

he tells Mrs. Farley sitting in the back, all in black.

Besides tales of shoveling coal, my dad also shared in response to my query what life was like in Lowell during the Depression and afterwards. He said, “We were poor, but so was everyone else. We had nothing else to compare it to, that just seemed to be the way that life was, and we made the best of it.”

While many of Tom’s Lowell poems capture the hopelessness of a young person looking for work in a city with one of the highest unemployment rates in the nation, others, like Coal provide vivid glimpses into the culture and society and of people “making the best of it” in post-World War Two Lowell.

Towards the end of Can Poetry Matter?, Dana Gioia writes,

“If poetry represents, as Ezra Pound maintained, ‘the most concentrated form of verbal expression,” it achieves its characteristic concision and intensity by acknowledging how words have been used before. Poems do not exist in isolation but share and exploit the history and literature of the language in which they are written. Although each new poem seeks to create a kind of temporary perfection in and of itself, it accomplishes this goal by recognizing the reader’s lifelong experience with words, images, symbols, stories, sounds, and ideas outside of its own text. By successfully employing the word or image that triggers a particular set of associations, a poem can condense immense amounts of intellectual, sensual, and emotional meaning into a single line or phrase.”

In Cummiskey Alley, Tom Sexton taps into our past, our memories, the stories we have heard, and the sense that has formed in us of what our community was like not all that long ago. His poems trigger “immense amounts of . . . meaning into a single line or phrase.”

Cummiskey Alley is available for purchase online from Loom Press and from Amazon.