Remembering 1968 (by Leo Racicot)

Remembering 1968

By Leo Racicot

Even now, almost sixty years later, when I hear the year 1968 mentioned, my mind instantly goes to April and June of that awful year. In April, the great Civil Rights leader, Martin Luther King, Jr., was gunned down by an assassin, James Earl Ray, on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, only a day after delivering his rousing. now historic I Have Been to the Mountaintop speech in that city. A terrible day for America; echoes of the murder of President John F. Kennedy a mere five years before hit Americans and the world hard. Watching King’s widow, Coretta, her grief-stricken face shrouded in black, her young children by her side, marching behind her slain husband’s coffin, brought back the still raw vision of First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy’s ravaged face as she walked the same sad route in 1963. Violence erupted across the country. The sight of seeing black protesters hosed down like dogs in the street by militia has never left me. Is it any wonder I am loathe to take myself back to those years.

In June, following a stirring victory acceptance speech at California’s Ambassador Hotel, presidential frontrunner, Robert Kennedy, left the stage to cheers and was gunned down in the kitchen area by extremist, Sirhan Sirhan. New York Giant’s defensive tackle, Roosevelt “Rosey” Grier restrained the killer, saving countless other lives. Someone placed a rosary in Kennedy’s hands as he lay in his own blood on the floor of the hotel. It was an instant flashback to his brother’s murder in 1963. America was expanding and contracting, expanding and contracting, with hate, with rage, with change, and seemed on the verge of implosion.

I remember that summer as being among the hottest. The decision was made to bring Kennedy’s body by train across America from Los Angeles to D.C., stopping along the way to let mourners pause and pray and weep. It was the slowest train ride ever witnessed. Millions came out to say “goodbye”. I remember we had a tiny black-and-white portable tv in the kitchen. Anthony Kalil was visiting and my sister was there. We brought a kitchen chair out onto the porch, placed the tv on top, and the three of us watched in absolute silence. It was I remember a summer of heat and abject terror. Protesters against the war in Vietnam and America’s involvement in “the unwinnable conflagration” took to the streets in record numbers across the nation.

It was a dangerous, menacing time, and here in Lowell, I remember having to walk by an encampment of Hell’s Angels off School Street across from Pevey Street. I was on my way to meet my friends, Scott Jackson and Jimmy Sullivan. When the three of us came out of their house, the Angels were blasting Eric Burdon and the Animals’ Sky Pilot so loudly, the ground underneath our feet was shaking and we decided to go around the long way. To this day, scratch my head in amazement that such a rowdy group of thugs were playing one of the era’s most demonstrative anti-Vietnam protest songs. Later, I was told they were readying themselves to act as security for a protest rally on South Common.

The airwaves, too, were filled with the anti-war anthems of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Tom Paxton. Between the loss of its beloved Bobby Kennedy and the Vietnam War, America and Americans were shattered, perhaps more so when Richard Nixon won White House in the Fall election.

Just as The Beatles had helped heal a grieving world in the aftermath of President Kennedy’s assassination by appearing suddenly on the world stage, taking music and culture by the horns, so they did the same when RFK was killed. In September, on The David Frost Show, they debuted what then became the longest running song ever recorded, Hey Jude. In a landmark performance. As the Fab Four began the song, they were joined on stage by dozens of members from the audience and crew, who joined them in the lyric, Nah Nah nah, nah nah nah nah nah nah nah nah Hey, Jude! Television and the music industry had never presented a production like it.

Within days, Hey Jude was everywhere. I have a wistful, very dear memory of being in Anthony Kalil’s basement. His cousin, Vanessa, was strumming her guitar, giving a group of us a solo mini-concert. She began with the mournful 500 Miles and her sad, brown eyes, her sad strumming made it even more mournful. She then segued into Hey, Jude, bidding us chime in on the chorus. I still see her there atop the stool, in that basement. Time has stood still on that visual. Vanessa, like so many others of our time, died young of a heroin overdose.

A summer day, a Saturday. Our mother wasn’t awake and up at the usual time. The right side of her body was slouched in the bed and the same side of her face was drooping, her lip twisted in an odd angle. I called an ambulance and it brought her to Lowell General Hospital. She’d had a stroke. Aunt Marie and Nana took the reins of Diane’s and my care. In those times, children weren’t allowed to visit patients in hospitals so, every night after she got out of work, Marie would take us to wait under our mother’s hospital room window. She’d go up and help Ma to the window where we’d wave and blow kisses. I still can see my mother in that window. Now, personal fear and sorrow were added to the ones in the news.

Marie had the great idea that she’d renovate our home. She thought if Ma came home to a wholly new apartment, it would help in the healing process. She recruited Diane and me to help. We accompanied her to carpet shops, paint and wallpaper stores, furniture stores and the three of us set out to transform the first floor of 5 Willie Street. After three weeks of physical therapy, our mother came back to herself and returned home. Boy, Marie couldn’t have been more wrong. Our mother had been eager to return home to familiar surroundings: her treasures, her treasured photographs. The shock of coming home to a strange place upset her and she cried and cried. She was never the same person after that scary summer. In the years ahead, she suffered one stroke after another. In fact, it seemed that every time she rallied once more from one, she’d have another. She died at the age of 84 from a cerebral hemorrhage on Thanksgiving Eve of that year.

In September of that year, I met Joe Markiewicz. We were freshmen starting out at Lowell High School. I was sitting in History Class, A period, with teacher Frank Finnerty. I was facing to the left talking with David McKean when I felt a tap on my shoulder. I turned to find this kid next to me, smiling. He said, “Aren’t you in my Phys. Ed. class, C period? I said, “I don’t know” and resumed chatting with David. At the next C period, I was toweling off after gym when, once again, there came a tap on my shoulder. It was the same kid from History Class. He said, “See!”. Thus began what has become a 57 years long friendship. So, 1968’s always been The Year I Met Joe, one of the few good things that terrible year brought me.

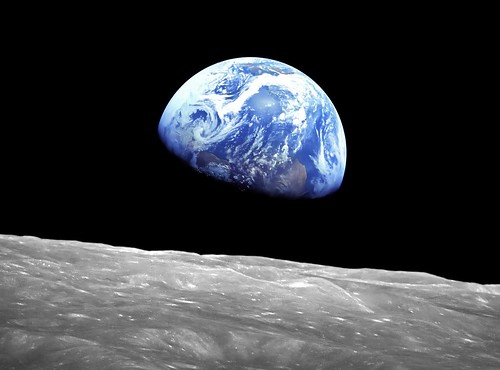

In December, NASA’s Apollo 8 crew headed for the moon. One of the astronauts, William Anders, was looking out the window of their space capsule when he spied the Earth coming up over the horizon and asked his colleague to hand him his camera. The shot he captured came to be known as Earthrise, the first ever view the world would have of what the Earth looked like from this perspective. The serene and green image of our Planet belied the chaos and confusion of what was happening on it. It gave hope to a hopeless world and ended the year on a high note.

Joe and other members of the Lowell High Math Club, 1968

Antiwar protestors in downtown Lowell, 1968

Hell’s Angels in Lowell, 1968

Fatally wouned RFK comforted by busboy Juan Romero Ambassador Hotel

Coretta Scott King & children in funeral procession of Martin Luther Kings Jr.

500 miles from my home

“Earthrise” by William Anders