Looking Back to 1968

Looking Back to 1968

by Paul Marion

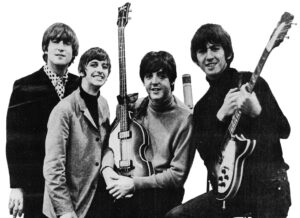

In late November 1968, my friend Susan April walked three miles in the rain from her home in Dracut, Mass., to buy the new Beatles double album at a Lowell record shop and hitchhiked home when the paper bag from the store began to soak through. Officially titled The Beatles, the album quickly became known to everyone as The White Album because of the all-white sleeve with the discreet band name. “I was one crazy fan,” she says. In those days, many of us in semi-rural Dracut had been born in the city, which served as our downtown for clothing stores, dentists, banks, and more.

Another friend of mine, John Suiter, a photographer in Chicago now, recalls “the beautiful color prints of the boys” which his college roommate had taped to the wall. Around the same time, the Rolling Stones released their Beggars Banquet recording in an off-white sleeve, a second “white album.” John says it took a week to “fully consider both albums . . . listening deeply, testing our understanding of the music and lyrics, poring over the liner notes for hidden communiques.” He adds that The Beatles’ plain white cover was excellent for rolling joints because “the small bits of weed stood out nicely.” The music didn’t catch hold of him and his friends until after winter break and the first half of the year. There were thirty new songs to absorb—in so many styles, with so much content.

My lifelong pal Paul Brouillette recalls high school friends who could afford to buy the album “debating for months whether it was as good as the previous year’s Sgt. Pepper record or a hodgepodge of John’s and Paul’s and George’s songs. Even Ringo had a song, ‘Don’t Pass Me By.’” Some friends thought the end result was a mess. He says, “In 1969, Beatles’ songs, the group and solo, such as ‘The Ballad of John and Yoko’ and ‘Give Peace a Chance,’ were topical or political but not as clever as the lyrics to ‘Back in the U.S.S.R.’ or as poetic as ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’ on The White Album.”

Speaking globally about the Fab Four, a growing-up classmate of mine, Willy LeMay of Nantucket island, says: “To have been lucky enough to come of age as those first Beatles songs hit the airwaves was akin to grabbing the lightning bolt right out of the sky.”

The Beatles (Wikimedia Commons image)

My response to the The White Album lagged. When the record landed, I was still listening to The Beatles from 1964 and 1967, A Hard Day’s Night and Magical Mystery Tour, plus a handful of number-one singles that I had on the small records, 45s. At later high school dances and beer-parties, The White Album soaked into my skin thanks to a hundred spins on the turntable and repeated eight-track tape plays. “Rocky Raccoon,” “Julia,” “Blackbird,” “Helter Skelter,” “The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill,” even the goofy “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” got my friends going in basements and living rooms.

Before and after the drinking age dropped to eighteen years old, we had in our crowd two sets of parents who said they’d rather have their kids drinking downstairs in “a cellar full of noise” than drag-racing on the highway and tossing empties out the window if a cruiser fired up its blue lights. Anyone was welcomed to stay over. Nobody in our tight group crashed a car. We did know kids who had been killed in road accidents.

We rocked out to The Beatles, Stones, Grand Funk Railroad, Crosby-Stills-Nash-and-Young, The Who, and others. But The White Album and Abbey Road dominated. For about ten minutes I was in a makeshift band that tried hard to copy “Rocky Raccoon,” a mash-up of folk and honky-tonk showing the group’s incredible range. I banged on a Sears catalog blue metal-flake snare drum and a hi-hat for the cymbal sound while others played guitar and an electric piano. As an older guy I go back to The White Album for select cuts like “Long, Long, Long,” a gem featuring George’s voice and guitar with Ringo’s massive drumming.

Many of my friends didn’t connect The White Album to politics at the time, even with the song “Revolution” on the disc and the not-so-subtle commentary of “Piggies” and “Happiness Is a Warm Gun.” We took The Beatles for music first and almost exclusively. That’s what we needed. The sound and the energy. We took them secondly for hair and clothes.

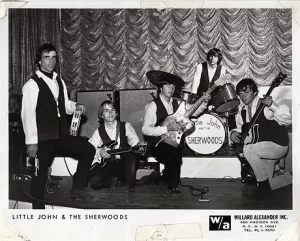

Music was the water to our fish in those years. The Doors played at the Commodore Ballroom in 1967, a performance hall near the Lowell train station. Their song “Light My Fire” was the number one in the country. The Commodore presented Cream, Jimi Hendrix, and the Kinks. Fans saw Vanilla Fudge, Moby Grape, Ultimate Spinach, and the 1910 Fruit Gum Company—note the food trend in names. The popular house band was Little John & the Sherwoods, like Paul Revere and the Raiders. Canobie Lake amusement park over the New Hampshire line showcased Sonny & Cher, Brenda Lee, and the Supremes. The record stores, Garnick’s and Record Lane, stocked new music. Two AM radio stations kept listeners informed and entertained.

Anchored by drummer Dave Arsenault, the Sherwoods practiced a few houses away from mine. I’d sit on the cement front steps and listen to the boys slinging fists across amped-up steel strings and banging away at the snare, tom-toms, and cymbals. The five-man band surfed on the British Invasion wave of bands. Band member Ed O’Neil told the Lowell Sun: “We’d rehearse forty to sixty hours a week. We’d go in sometimes at eleven in the morning and rehearse until eleven, twelve at night. Plus, we’d play there three times a week.”

Little John & the Sherwoods publicity photo

The Sherwoods cut a single, “Long Hair” on one side and “Rag Bag” on the other. A thousand kids packed the Commodore at the height of the Sixties. The Sherwoods had chances to tour with the Beach Boys and Young Rascals when they were hot, but their manager held them to the house-band contract that kept them in Lowell to open for the Yardbirds, Neil Diamond, and other chart-toppers. When Arsenault got drafted into the Army in 1966, his bandmates gave him a public haircut on stage. That was the start of the group’s unraveling.

*****

What else was going on? All the big and little parts of daily life in the Merrimack River Valley.

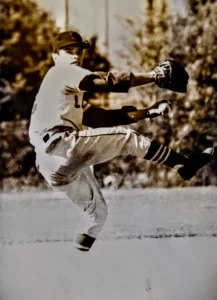

In the spring of 1968, 2500 people at Shedd Park in the Belvidere neighborhood cheered for their teams in a baseball game. It was the largest baseball crowd in the history of Lowell High, which lost to its cross-town rival, Keith Academy, a Catholic high school for guys only. “They had a better team,” said Brian J. Martin of Lowell High, who had pitched a perfect game two weeks earlier.

The Keith game was still close when Brian ripped a long line drive that was snagged out of the air in a leaping grab that snuffed out a likely three-run homer. A school of about 400 students, Keith won the Catholic Conference baseball championship and played in the Eastern Mass. Championship game, losing to Reading, 2-1.

Baseball was booming in the area, in part because of the Red Sox’s “Impossible Dream” season in 1967 when the Sox won the American League pennant for the first time in decades and then lost the World Series in seven games to the St. Louis Cardinals.

Future Lowell Mayor and high school Headmaster Brian J. Martin, pitching for Lowell High School, 1968 (courtesy of the “Room 50” blog, 6/24/18)

*****

For context.

Dracut’s population in 1968 was about 18,000 and more than 90 percent White; Lowell had 94,000 people: 92 percent White, 5 percent Hispanic, 1 percent Black, and .7 percent Asian. Twenty thousand people had left the city between 1920 and 1960, many of them World War II veterans moving their young families to their first homes in the ring of suburbs, Billerica, Chelmsford, Dracut, Tewksbury, Tyngsborough.

By 2020, Lowell’s population, having grown to 115,554 people, was 40.59 percent White (non-Hispanic), 21.68 percent Hispanic, 8.28 percent Black, and 22.11 percent Asian. The 2024 population was 120,418, according to U.S. Census records.

After World War II, unemployment in the city had risen and stayed high. The local authorities began tearing down old houses, tenements, and business structures, hoping to attract new “electronics” companies with open space for expansion. According to one report by neighborhood leaders: “The Lowell region was one of eight major urban centers in the U.S. classified as places with chronic unemployment, and as late as 1965 the jobless rate was fifty percent higher than the national average. From economic deprivation grew crime, neglect of the young and the elderly, poor physical and mental health, dependence of public welfare programs, and the steady withering of community involvement and spirit.”

In 1968, a friend of mine walked to Keith Academy from his home across the river from downtown Lowell.

I could have taken a bus, but walking the route, surrounded by empty mill buildings with broken windows, somehow reinforced the new independence I felt since leaving grammar school. Everything was bigger, and older, than Dracut, the town I knew. History had been made here—had been—but the Lowell I walked through every day from 1968 to 1970 was spent and gray, punctuated only by the burnt-orange brick mill walls.

Community leaders involved in the federal Model Cities urban renewal project talked about rehabilitating Lowell’s history, mills, and canals as a way to revive the spirit and economy of the city. At the grassroots, activists planned a way forward. They believed in education as a stimulant and pictured a “City of Learning” in a museum-without-walls.

Ten years of effort led to tremendous change by 1978, when the city was named a national park, commemorating the American Industrial Revolution of the mid-1800s. The new computer industry created jobs in the region. Wang Laboratories, Digital Equipment Corp., Data General, and other high-tech companies dominated headlines as the boom radiated outward from the Route 128 belt, America’s Technology Highway, to Route 495, Lowell’s modern-day Merrimack River.

*****

In the nation and world every month of 1968 brought explosive news. January’s brutal Tet Offensive attack against U.S. and South Vietnamese forces by North Vietnam’s army and Viet Cong guerrillas in the south exposed President Lyndon B. Johnson’s deception about the enemy’s strength. (Tet refers to the Lunar New Year holiday in Vietnam.) Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in April, and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy during the Democratic Party’s presidential primary contest in June. Social and political unrest spread. Student turmoil in France in May and Mexico City in the summer, and then the Soviet Union’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in August, kept the global pot boiling over.

South Vietnamese army rangers defending Saigon in the winter of 1968 (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

By 1968, the Vietnam War was in the veins of places like Dracut and Lowell.

In September 1965, Army soldier Donald L. Arcand, nineteen years old, was killed in South Vietnam near the end of his tour of duty—the first young man from Lowell to die in that war. He was a door gunner in a UH-IB helicopter that was shot down by fighters on the ground. Private First Class Arcand was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. He had played basketball at St Joseph’s High School, most of whose students had French roots.

Jane Hoye of Lowell, who was engaged to Donald when he died, wrote years later that she felt an “indescribable sadness” at the news of his death. “There were no men in Lowell in those days. They were all drafted,” she added, according to the Lowell Sun.”

Michael J. Monahan from Dracut Center was a Marine Corps radio operator in South Vietnam in September 1966 when he was shot and killed in combat. He was almost nineteen years old and had been in uniform for six months. Local historian Rebecca Duda describes him as “a brilliant student who wanted to help others, an aspiring doctor.” A graduate of Keith Academy, he left Boston College in his sophomore year to serve in the military. Town officials paid tribute to his sacrifice in a monument at a newly dedicated Monahan Park on Pleasant Street.

A young guy whom I knew by sight from my Dracut neighborhood was killed in Vietnam in 1969. Six years older than me, he was a sergeant in the Air Force when he died in Gia Dinh Province, a “ground casualty,” per military records. A quiet guy who lived up the hill from my house, his name now tops a steel post set in a grassy crossroads at Hildreth Street and New Boston Road where I caught the high school bus. Now it’s a hero square: Turner Square. When I finally visited the bright black Wall in hot and steamy white-stone Washington, D.C., and felt the incisions in its mirror-face, I searched for Sergeant Turner’s name: His dates are 31 Jan 48, 17 Aug 69. Daniel R. Turner. He’s on Panel 19 West, Line 57. Just like the neighborhood sign.

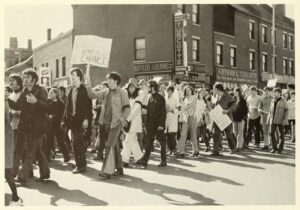

City officials in 1969 dedicated Arcand Drive in honor of Donald—it’s a prominent street in front of the John F. Kennedy Civic Center and Lowell City Hall. The same year antiwar activists in Massachusetts began organizing peace marches in the old factory cities where the military was getting so many of its members. They wanted to save lives. In Lowell, some young people and older residents listened to the organizers describe a plan for an antiwar march in 1970. When the day of the march came, a few hundred protesting students, community members, and hard-core, out-of-town antiwar activists with provocative flags and banners encountered violent resistance from hard-nosed Lowell guys who detested what they believed were anti-American symbols and chants.

Young Steve O’Connor was there with his older brother.

I didn’t know anything about politics or the war, but I remember the chant: Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh. The Viet Cong are gonna win!

I asked my brother Rory, “Aren’t they the enemy? There were lots of Free Bobby Seale signs, too, backing the Black Panther firebrand.”

A guy, a badass, who was the brother of a girl I knew, kicked a protesting sign-holder in the balls so hard I could almost feel it, nearly lifting the guy off the ground. He dropped the sign and fell like a ton of bricks. You know that famous photo of a Frenchman crying as the Nazi soldiers marched into Paris? It was like that. A man who was probably a World War II veteran with an American flag cried on the sidewalk.

One of the march organizers, Michael Ansara, would later write: “We needed to listen as much as we talked. More than anything else we needed to be respectful of the people we wanted to reach and organize—and we were going about it the wrong way.” Ansara’s friends later met with the Lowell guys who had attacked them on the streets to try to find a common purpose—to save lives.

The previous year, there had been another peace march in Lowell with a better outcome. The community staged an action in solidarity with the national Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam. In Boston, 100,000 people assembled to protest, one of many demonstrations across the country. My friend Paul was a sophomore in high school in October 1969 when he and several friends joined a throng of people:

We walked up Merrimack Street to City Hall under a blue sky with the sun shining through yellow maple leaves. The day was crisp and clear as only October can be at times. Streets were closed. More people joined the crowd when we passed St. Anne’s Church and Lowell High School. The mood was somber. We were protesting the war, exercising new muscles, and finding a new voice. For many of us, it was our first political act.

I felt some concern about participating, as my sister’s boyfriend was stationed in Vietnam, and, of course, my father saw any march like that as unpatriotic. But, again, it was like an initial coming-out and acknowledging that I could deal with possible repercussions.

Lowell antiwar march, 1969 (photo courtesy of Downtown Lowell page on Facebook)

*****

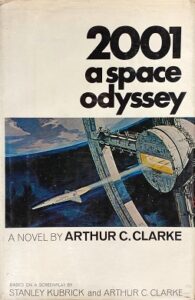

A final thought on 1968. The weekend after Easter, my brother Richard took me to the new Showcase Cinema complex in Lawrence close to Route 495, whose central theater had the largest screen in the area. I was eager to see the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, which, for good reasons, has reached the status of a cathedral among film religionists.

I didn’t get everything at first view, and I still don’t understand fully the haunting metal monolith and why the all-knowing spacecraft computer frazzed out. I should revisit Arthur C. Clarke’s novel to explore the story more deeply. When I learned that the computer was named HAL because the three letters precede IBM, I appreciated that inside joke. The visual presentation was nothing I’d seen before. The scope of the narrative, the space world gadgets and vehicles, the mythic vibrations.

Most of all, though, I came away mesmerized by what is called “the Star Gate sequence.” For almost ten minutes, I was pinned in my padded seat while a multi-colored projection washed my eyes, my whole body. I felt as if I was thrusting forward and being pushed back simultaneously. The effect was both kaleidoscopic and a psychedelic tunnel ride, the visual data rushing past on the sides as I, the viewer, arrowed ahead, slipping into the chromatic void through a vertical seam and then flattening to horizontal slicing.

Through ages of techno-grid travel the context shifts to a morphology that feels familiar even as it stays strange. From a machine world, from an optics carnival, we are transported to places vaguely land-and-sea-like. I walked into the sunlight feeling like a hole had been drilled in my head, painlessly, and filled with dream juice that I could not have identified when we got to the show 142 minutes before.

In a year not half-over that already felt messily human and would get uglier and more spectacular, this film, a work of art, had yanked me out of my limited daily experience. Space fascinated me from the start, whether in science fiction or science nonfiction. At the end of the year, the Apollo 8 astronauts orbited the moon and safely touched down in the Atlantic Ocean. Like the Star Gate Sequence, they gave us a new visual, a photograph by Air Force officer William Anders that is called Earthrise, made on Christmas Eve. About half of our planet, blue seas wrapped in white clouds, is seen above a slice of the Moon’s gray surface amid black space.

Anders said, “We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.”

*****

Paul Marion, Copyright (c) 2025

Thanks for bringing me back to a time that due to my age was before I could understand what was happening around me. Captivating!

Paul, I so love your writing. Brings it all back. Enamoured of this line especially: “In a year not half-over that already felt messily human and would get uglier…” Thank you for being our Dracut-Lowell muse-and-chronicler.

Thanks, Gerry and Susan for the encouraging words. I’m glad the writing hit home.

Love it. White Album rules, by the way. LJ & Sherwoods’ “Long Hair” is a stone garage-rock classic. Spent time with them all to write a story when they reunited some years back. People in love with music.

They called Jack Kerouac “Memory Babe,” but Paul, you’re right up there, doing what writers and historians do, describing and interpreting the past, and reminding some of us of the nearly forgotten days we’ve lived.

I took guitar lessons from “Litte John “ himself, not that they helped me get and better.

68 was a seminal year in many ways that I think people who weren’t there would have difficulty relating to. In fact, I can’t think of a more important one culturally, politically, and musically..

Paul, this is a well-written chronicle of that era, covering music, sports, war, protests, politics, and even census records — it’s all here and very engaging.

I lived five minutes from the Commodore; saw the Doors, The Raiders, Yardbirds, and danced to the Sherwoods every Saturday night, and used the back lounge to make out with girlfriends.

But 1968 was a traumatic and pivotal year for me. I turned 18 on April 1, and three days later, MLK was assassinated. I received my letter to report for active duty on June 3, and two days after that, RFK was assassinated! By August, I was at Fort Polk, LA, for boot camp.

The White Album was released in November, and I didn’t get to hear it until I came home for Christmas furlough; my gorgeous French fiancée from Dracut had bought it for me.

I then spent six anxious years in the Army Reserves ( and hung out with hippies) while being trained to break up war protests. I prayed I’d never end up in a situation like the guardsmen at Kent State, leaving four dead on the ground.

I wrote about this in my piece, “The Letter and The Counterculture.” Dick posted it last June in this blog:

https://richardhowe.com/2024/06/27/the-letter-and-the-counterculture/

It’s the centerpiece of my forthcoming collection of short stories, a nostalgic portrait of Lowell, in the ‘60s and ‘70s, titled “Simpler Times in The Spindle City.”

Paul, thanks for reviving our boomer memories. I needed to take a break from writing and promoting my novel, “The Vulnerable.”

I’m now on Spotify listening to Dear Prudence… won’t you come out and play.

How great was Sixties music? On November 25, 1968 the Beatles White Album AND the Kinks Village Green Preservation Society (perhaps the greatest low-selling album in the States at the time) was released. A week later Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks album was released, to be followed by the release of the Rolling Stones Beggar’s Banquet album a week later. Anyone who lived it knows there will never be another era of greater popular music than the sixties. Thanks to the Beatles, almost every male teen in the country started playing a guitar of the drums and a million bands were started with boys wanting to be John, Paul, George and Ringo. So the pool of baby boomers who played music was larger than any other era. How many kids are starting bands today, or learning how to play instruments or sing without pitch improvement devices? Even though the population is much larger today than in the sixties, the population of young people who wanted to be a singer or musician was much larger in the 60’s.

Dave, Steve, Paul, Ed, Charlie, Susan, Gerry. Thanks for joining the chorus for this post whose “music” is much more complex than I had the space and time to compose. That’s the power of the Howe blog. The readers can take any post to the next level. I’m glad the essay hit home for a bunch of folks. I look forward to your future stories, essays, poems, photographs, paintings, reports, accounts, documents—whether online, in books, magazines, journals, newspapers, out loud at events, or however they may take form. Keep the creative line moving . . .

My father was ready to disown me after two protest rallies in that era.

The first was after Cardinal Cushing’s final and irrevocable decision to close Keith Academy. The four senior class officers, Dan O’Brien, Dave McKeirnan, Rick Lalime and I held up signs across from the school saying “Cardinal Unfair to Lowell”. WBZ tv filmed and showed the event on the evening news.

As a deeply conservative Catholic, BC ‘42 alum, Dad was distinctly not at all pleased.

A few months later I joined the huge throng at Shedd Park at which “the Mobe” rallied us against the war. Ironically both of my parents watched the proceedings from a discreet distance.

By then, I was not only arguably a religious heretic but also deeply unpatriotic.

Fortunately we kept talking through all this, and although we were never going to reach agreement on these ultimately divisive issues, the relationship didn’t break, as it did for many others.

Now if the military had drafted me once I turned 18, and I had had a really low draft number, well, who knows?

As it turned out while a few from my birth year of 1952 were drafted, I escaped that noose.

But it was a near thing, and even back then, I deeply respected those who served at the peril of life and limb.

John Lamond

Beautiful story, Paul as always. A beautiful blend of the two most powerful stories of ‘our’ generation, the war and the beginning of the rock revolution. I put ‘our’ in quotes because I was 10 in 1968, too young for the war and the beautiful beginning of the sound track of our lives.

One thing I came to appreciate very early on was the absolutely amazing story of how the Beatles chose their name. I think one cannot talk about the British Invasion without at least giving some credit to the fact that the Beatles style of music was directly and completely influenced by that one brave man and his band, in America, who chose to do things differently.

Beatles exist because of Crickets before them. The day the music died is forever tied into our rock revolution. Go Buddy!!!

Paul, your essay brilliantly captures the era’s electric pulse. I had but a minute but over-spent because my heart refused to allow my eyes to quit and my mind to savor. My coffee is now cold and abandoned under a Keurig.

On the war side of things in 1968 I was one of those working class kids who was brainwashed by the Lowell Sun, Boston Herald & even some Catholic clergy who assigned us “Treasure Chest” magazines (anybody remember their hero called “Chuck WHITE?) that spewed all kinds of the Commies were gonna invade us and turn us into the kind of nation where goon squads like ICE would come and cart innocents away in the night if we didn’t go to Vietnam to stop someone called the Viet Cong from throwing babies on bayonets for the fun of it.

But because John Lennon became my cultural hero, who I especially embraced because I liked the fact that he was a tough working class kid from Liverpool, and an even dumpier, bigger and tougher city than Lowell, opposed the War, I had to find out why because I knew he wasn’t some wimp who opposed the war because he was just a gutless hippy who would’ve cried pacifism to avoid fighting the Nazis then, or the bad guy Commies now.

I probably would’ve been one of the guys who would’ve wanted to beat up the protesters too, but when I needed to find out why a cool, tough guy like John Lennon and now Muhammad Ali, my favorite sports star, who certainly wasn’t a wimp, was willing to go to prison, could say we were wrong to be there as well, I went to the library and started to read stuff beyond the “Treasure Chest” the Lowell Sun and Boston Herald and became pissed off as hell and felt like a fool for being easily manipulated when I realized the truth was that WE were the invaders of a country that didn’t want us and was unleashing Nazi Germany like power against a nation that was no threat to us. And not only were the older brothers of my friends getting killed and maimed there, it was being done to benefit the elite who could opt out with “bone spurs” but still be considered heroes, while young kids opposing the war could be imprisoned or beaten up for trying to tell the truth about what was happening in Vietnam. And even worse, that America was sometimes the ones that often let war atrocities go unpunished and even celebrate bastards like Lt. Calley become HEROES instead of villains for murdering women and children in places like My Lai. Now instead of wanting to attack protester, I wanted to be able to kick Lt. Calley and his enablers so hard to drive his balls up to his eyeballs.

Ironically, I ended up in the Army and just missed going to Vietnam because I was in Basic Training when the order came down that no NEW troops were being sent there and they would begin pulling soldiers back. However, I served in a unit where almost every older soldier had been deployed to Vietnam and I heard their horror stories, saw their PTSD and found out about how many of them had suspected they were ill because of herbicides (later to be identified as Agent Orange) only to find out years later they had been correct. I lost a friend from cancer because of it and I later fought through my involvement with Fair Share (ironically the group Michael Ansara had started and who I worked with as a member of the statewide Fair Share Board’s Executive committee while he was the group’s Executive Director) and in the name of my friend Tim Reid of Fall River who died from Agent Orange, fought with then State Senator (and later Congressperson) John Olver to pass the first formal request through the Massachusetts Democratic Convention to demand the state of Massachusetts investigate the harmful effects of Agent Orange on Vietnam vets who were exposed to it and to call on the federal government to do so as well, with the intent of compensating any vets or their families if their harmful effects were proven.

So yeah, sixties music AND my political awakening both occurred simultaneously. It also shows the power of art to cut through institutional brainwashing and learn to speak truth to power.

Charlie (again), Jacqueline, Jim R, and John L, thanks so much for your responses to the essay about 1968. Every comment adds to the texture of the original writing. I know all the replies are heartfelt and full of thought when it comes to that intense period of the late Sixties to early Seventies. I was 18 in 1972 and holding a low Draft Lottery number when the word came down that the Selective Service draft of young men would be suspended. The war was still raging but being handed over to the South Vietnamese defenders. I’m still haunted by the close call. The whole crazy world was in our faces in those days even as we tried to live daily lives with some sense of normalcy.

Just to be on the safe side in this age lacking irony and one has difficulty distinguishing sarcastic satire from reality, when I use phrases like “gutless hippies” in my earlier comment, it was a portrayal of what I was led to believe at the time, not by what I found out later to be a perception that was planted in me so I could block out what they were actually saying about the war, and dismiss them as the character-assassinated caricatures. There was nothing gutless about those who risked beatings and/or prison to stand up against what they discovered to be a lie that was getting both the Vietnamese and American boys sent to fight them killed.

WBCN

I Feel Free

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=prnbF8Eagdg&t=7s&pp=2AEHkAIB

Paul, you too have grabbed a “lightning bolt right out of the sky” with this free-associative mind-ramble across piece of real estate and time. I was living it in a different part of the world, but it didn’t feel much different.

Good to see Michael Ansara’s new book “The Hard Work of Hope” getting some strong notice. God knows we all need some hope.

Solid, brother.

AMEN to Paul’s deliciously-energizing text and AMEN to the comments above! The Beatles worshipper kid I was (and still am) in 1968 thanks you!