Time Lapse

Time Lapse

By David Daniel

I am sitting in my night class and Mr. Crutchfield, the instructor, is talking about time lapse photography and how you can manipulate an image by the amount of light you permit to enter the camera. I’m not too clear on what this means, for at the moment my mind is wandering.

I’m thinking about a visit I paid that afternoon to Mrs. Ramos. I go once a month and sit with her in her tiny apartment in a subsidized housing project in South Lowell. She lives alone and seems happy for the company, someone who’ll just sit awhile. She serves coffee. There doesn’t have to be talk, though her English isn’t bad. I don’t know more than a word or two of Spanish. Sometimes she’ll tell me about her son José, who died a year ago. Her sadness is like a Caribbean storm, sudden, intense at times, then passing on. I judge Mrs. Ramos to be in her mid forties, though it’s difficult to know for sure. She’s been here only a short while. You can see she was once a pretty woman, but care has laid a heavy hand on her. Her sorrow never goes away completely.

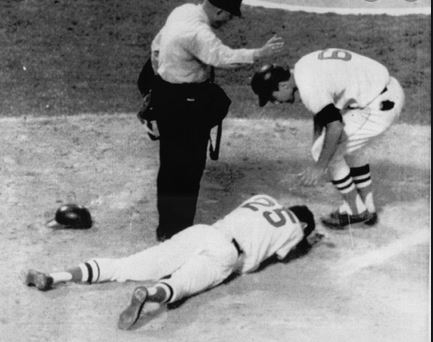

José Ramos was twenty-one. There are photographs of him on small end tables in the apartment. He was a promising baseball player, an outfielder. He loved the game from childhood, growing up in Santo Domingo. He had a future. He was a good glove and a strong stick, had already hit twenty-two home runs for the class-A short season Red Sox affiliate here in Lowell. He was struck by a pitch that somehow caught a bit of temple. Unlike the Show, there’s no one whose job it is to make sure the helmets fit. He was in a coma for ten days before he died. His mother talks about him and for a brief time he comes alive again.

“You must like baseball?” she asked me the first time I visited.

I told her the truth. I don’t care for it. I did, once, but now I’m trying to get interested in photography.

“—and get the effect by using a sepia tone,” Mr. Crutchfield says, and I realize I’ve missed the last part of his instruction. I’m embarrassed to ask him to repeat it, and now it’s a new thing to feel anxious about. I’ll wait ’til after class. He’s got ten of us in the adult evening ed course, about third of whom, like me, are beginners in photography.

The pictures of José Ramos in his mother’s small apartment show him in different stages of his development as a ballplayer. In the more recent photos he has put on weight and upper body size and there’s a sense of power in him that suggests danger to opposing pitchers. And yet, in the casual photos, when he’s not in his uniform, he’s got sweetness in his look, so different from the glower he shows when he’s standing at home plate with a bat in his hands.

I realize I don’t want to wait until the end of class to speak with Mr. Crutchfield, so in the five-minute break he always gives us—and gives himself, to go outside and smoke a cigarette—I go out, too. He’s with another student, a pale blond girl of about my age, twenty or so. They’re smoking and talking, but I can overhear that it’s not about class or photography. As the cigarettes get shorter, my anxiety is growing. Finally, I interrupt.

“Billy,” he says, “I’m speaking with Alison, but we’ve got to get back. Can it wait ’til after class, guy?”

He’s not being mean; he just doesn’t understand that I’m jumping from my skin. I won’t be able to sit through another hour of class.

“I’m gonna have to leave early tonight,” I say quickly. “That’s what I wanted to tell you, sir.”

Alison steps on her cigarette and wanders back into the building. Mr. Crutchfield looks at me. “Not focusing?” he says, and then smiles. “Joke.”

“Oh. I get it.” He’s a good-natured guy.

“Well, I’ll see you next week then. Hang in, okay. There’s a learning curve, but this isn’t brain surgery.”

I head for the parking lot, which is full of shadows. My arm tenses, wanting to move with a life of its own, and I manage to still it only by gripping the door handle of my car. My mind, however, won’t settle down, wanting more light, worrying at the idea: At nineteen, what did I know? Could I have sorted out appearances and realities? I realize that unconsciously my fingers on the handle have the grip for a fastball. Thinking of José Ramos, the sweet one in the photographs in his broken mother’s apartment, José without the glower, I’m obsessing over the question I can’t ever seem to answer: did I throw a questionable pitch?

I didn’t see that ending coming, Dave, but it made perfect sense. Yu’ve become a master of flash fiction.

The ending, of course, is killer. But what I also like a lot is how the narrator and the story goes from a class on photography, to an apartment with a series of photos, to a single photo, to an indelible image that cannot be forgotten or focused on. I don’t know from cameras but it is interesting how the reader gets drawn in to the recesses and only at the end, at least for the reader, is there light and sense of the complete picture, frozen as it is in the kid’s memory.Really is masterful.

Love this one.